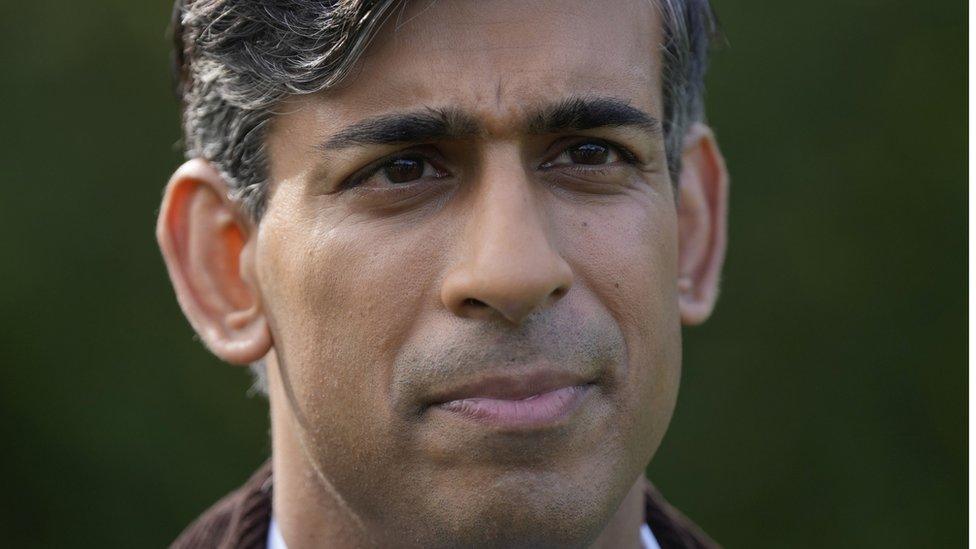

Chris Mason: The week Rishi Sunak changed gear ahead of general election

- Published

The pace is quickening. The collective heart rate of Westminster is notching up.

The summit - a general election - is in sight, even if the time it'll take to reach it is still guesswork.

There has to be an election by the end of January 2025 at the absolute latest.

"I think it's going to be May!" one former cabinet minister confided to me, suggesting the broad Westminster consensus that the election is most likely to be in autumn 2024 might be wrong.

In truth, the precise timing will be decided by the prime minister and a tiny group of people around him; his best man turned political secretary James Forsyth, his chief of staff Liam Booth Smith and election strategist Issac Levido perhaps among a very limited few.

And they have no reason to have decided for certain yet anyway.

Stuff that is yet to happen could still play a big part in when polling day actually is.

But the gradient is steepening, the air is increasingly rarefied.

You can smell it, feel it, see it around Westminster.

'Flashing lights wherever you look'

And the same will be true at the party conferences, starting with the gathering of Liberal Democrats in Bournemouth this weekend.

Rishi Sunak's shift on green policies - revealed first by the BBC - felt like a beacon marking out this change.

The PM says "we have to change how we do politics" as he speaks about climate change and its impact on families.

Conservative campaign headquarters had been primed in advance and had their social media messaging ready to go, even if the leak to the BBC played havoc with their plans for 24 hours.

But there are other flashing lights wherever you look.

Not only was the man who is miles ahead in the polls glad-handing the president of France.

But when Sky News pointed out that Labour leader Keir Starmer had said "we don't want to diverge" , externalfrom the European Union if he becomes prime minister, cabinet minister Michael Gove was out in front of a camera having a pop at him within an hour or so.

Where a secretary of state instantly pounced on arguably rather loose language from Sir Keir, other cabinet ministers quickly followed suit.

The speed of the reaction was another illustration of campaign machines cranking up a gear.

On this week's show are defence secretary Grant Shapps, Lib Dem leader Ed Davey and Labour's shadow chief secretary to the treasury, Darren Jones

Watch live on BBC One and iPlayer from 09:00 BST on Sunday

Follow latest updates in text and video on the BBC News website from 08:00 BST

So what happens next?

Three sentences from Rishi Sunak the other day sketch out a map for him for the months ahead.

He said: "The real choice confronting us is do we really want to change our country and build a better future for our children, or do we want to carry on as we are? I have made my decision: we are going to change. And over the coming months, I will set out a series of long-term decisions to deliver that change."

The context is this: the prime minister has steadied things, the government isn't about to collapse, but the Conservative party is in a massive hole in the opinion polls, and so is Mr Sunak himself.

A new poll for YouGov, external suggests he is personally more unpopular than at any time since he became prime minister.

And No10 has concluded it is time to be more aggressive. As I wrote a few weeks ago, that has involved beefing up the team at the top.

'Education shake-up'

So what could we hear from them this autumn?

An education shake-up in England is being considered. One idea is A-levels are scrapped and replaced with a baccalaureate in which English and maths become compulsory elements of post-16 education.

What about transport? Ministers are studiously ducking questions on whether HS2, the high-speed rail line between Manchester and London, is actually going to be built in full.

One idea being discussed privately in government, I hear, is that the new line joins the existing West Coast Mainline at Handsacre in Staffordshire, 20 miles north of Birmingham.

In this scenario, trains to and from Manchester, for instance, could use the HS2 line but be on the existing line from the West Midlands to the north west of England.

That would amount to a significant junking of a big chunk of the planned project.

Another option would be for the government to push back the time frame for delivering the northern leg of HS2.

Both could free up money for east-west rail improvements in the north of England and, depending on the option chosen, probably leave money to spare.

Next, the European Convention on Human Rights.

Some senior Conservatives, including cabinet ministers, want the Tories to advocate leaving the convention if the plan to send migrants to Rwanda is rejected next month by the Supreme Court.

"Nothing is off the table," immigration minister Robert Jenrick told the BBC this week.

There is frustration at the role of the European Court of Human Rights in stopping flights for asylum seekers taking off last year.

But even those keen on withdrawal acknowledge privately "it'd be like Brexit 2.0" - complicated and controversial.

Labour 'hesitant'

Where does all of this leave Labour?

Sir Keir Starmer met French President Emmanuel Macron in France this week

It leaves them forced to take a position.

And so determined are they to project a sense of being economically credible, when the Conservatives advocate or imply a policy shift, the Opposition has been hesitant to instantly reject it.

Take HS2, where shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves is very cautious - and so, like government ministers, won't unequivocally back the full project, as you can hear on the BBC's Newscast, external.

Why? Labour argue if they inherit projects in a mess, that will inform what they can do.

But they also don't want big gaps opening up between their spending promises and those of the Tories, when the public finances are so squeezed.

As for Labour's own policy ideas, they have to work out a timeframe for unveiling them without knowing when the election will happen.

And that isn't easy.

But neither, for the moment, is Rishi Sunak's situation.

The Conservatives' great knack - over the last 13 years in government but also, arguably, over the last century and more - has been a shapeshifting sensibility to mould to the moment.

It can and has proven very successful, but there is evidence too that there are diminishing returns to reinvention.

Writing for Conservative Home, external, James Frayne argues the change in green policies might only register for many as something the Tories have changed their mind on.

Some of the challenges for the fifth prime minister of a party's long run in power are simply inescapable.

Related topics

- Published21 September 2023

- Published27 September 2023

- Published23 September 2023