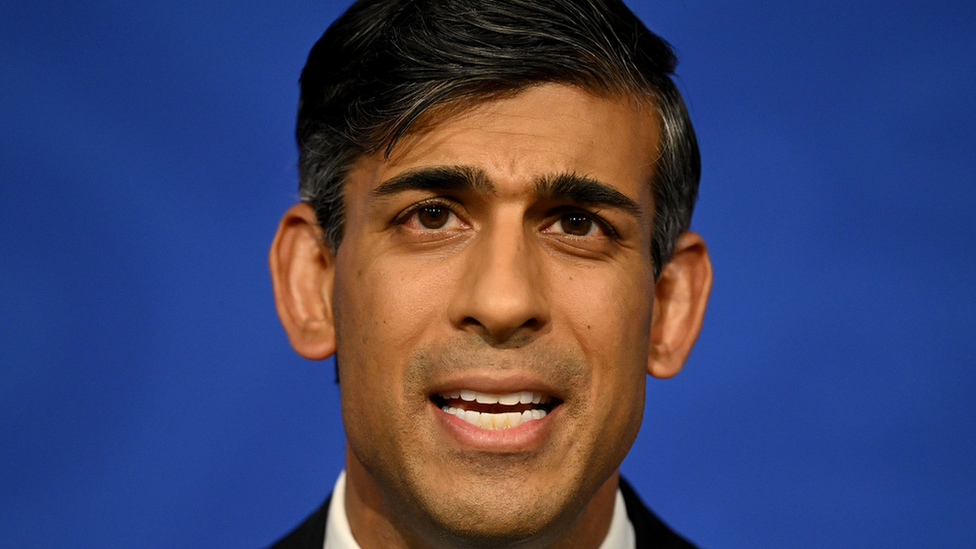

Chris Mason: Eyebrows raised over Sunak's Plan B for Rwanda

- Published

The row over the Rwanda plan is a reminder of two fundamentals.

Firstly, the geography of power in our democracy.

Across Parliament Square from the Commons and the Lords, stands the Supreme Court.

The power of the lawmakers on one side of the grass.

The power of the rule of law on the other.

Secondly, the contemporary challenge to richer countries globally of illegal migration.

It is huge.

And the UK is not alone in considering new options and wondering if decades old conventions can survive.

If you are in government confronting a colossal challenge and the law isn't working for you, you can change the law.

And that is what ministers now plan to do.

But critics of the government - from its former ministers to opposition parties - claim Rishi Sunak has made a difficult situation harder.

They say - and his home secretary of just the other day Suella Braverman is among them - that he was too blinkered for too long in believing Plan A would work.

And there is an open scepticism from some on his own side about the prospects of his new plan working.

It is out of this humiliation at the hands of the Supreme Court that his Plan B bubbles: a treaty with Rwanda and a willingness to confront - albeit without the details of precisely how - the European Convention on Human Rights.

Rishi Sunak remains determined to be seen to take this on for he concludes millions want him to.

And he knows plenty of Conservative MPs demand that he does, fearing they will lose their seats if he doesn't.

But it is justified to be sceptical about how neatly, if at all, this can be executed.

Because having spent 18 months bogged down in a series of courts, ministers now confront the thickets of legislation, courts and conventions towering around them, which their new approach has to navigate.

None of this screams speed, and yet their rhetoric still does.

They hold to the claim that they want migrants on planes to Rwanda by the spring - which isn't wildly different from what was likely to be the rough timetable if the Supreme Court had given their initial plan the thumbs up.

So raising an eyebrow about them pulling it off seems reasonable.

What is clear is they are desperate to communicate their desire to do so in an unvarnished way - knowing the argument will be alive within the Conservative Party, around parliament and around the country as we head into a general election campaign year.

Related topics

- Published16 November 2023