Politicians flounder as they wrestle with race rows

- Published

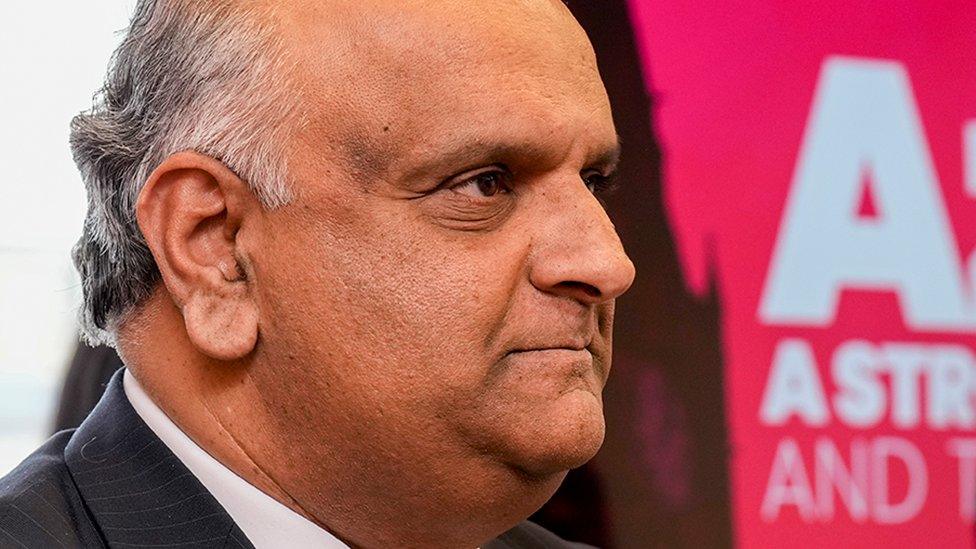

Frank Hester. Diane Abbott. Lee Anderson. Azhar Ali.

Four people, over the last four weeks or so, who tell us something about money, power, individuals and institutions.

And also tell us something about language and labels.

Their capacity to anger, enrage, offend.

It is a month to the day since the Labour Party disowned its then-candidate Azhar Ali in the Rochdale by election, over alleged antisemitism he apologised for.

What had come before?

Turmoil about what to do; a party grappling with what should be the appropriate response.

Senior figures sent out to do interviews with a line to take that crumbled not long later. The party accused of condemnation in words, but not in actions. Until that is, they chose to act.

Then there was the row about Lee Anderson. The now-Reform UK MP and former Conservative deputy chairman and a debate with language and labels at its core.

Mr Anderson's remarks about the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, who is Muslim, were branded "unacceptable" by the prime minister. Others, including Mr Khan, said they were racist and Islamophobic.

Hamas's horrific attacks in Israel in October, and Israel's subsequent war in Gaza has undoubtedly sharpened some of these debates.

But they can't all be traced back to recent events in the Middle East.

Frank Hester's alleged comments date from 2019.

Here we have a hugely successful businessman from humble beginnings.

A man of Irish heritage who has talked of the abuse he suffered as a child because of where he was from.

A man with a diverse workforce who has become one of the Conservative Party's biggest donors under the country's first British Asian Prime Minister.

A man now condemned by that prime minister for uttering racist remarks.

And it is to Mr Sunak in particular that Mr Hester has been drawn, as opposed to the Conservative Party in general. For years, he said, he voted for the Green Party.

'Remorse accepted'

The government's line - having spent a day not calling the alleged remarks racist - is, actually, they were.

But Mr Sunak believes his "remorse should be accepted," as he put it at Prime Minister's Questions.

In other words, an instinct for tolerance should extend to those who have articulated apparent intolerance.

And there is a distinction, they argue, between a racist remark and being a racist person.

It taps into another keenly contested contemporary concept - the idea of being "cancelled".

The argument, from some, that those who preach tolerance seek to ban or remove some people from the public stage altogether.

Diane Abbott is the UK's longest-serving black MP

It is into this territory that the ongoing discussion about Mr Hester's donations - and whether they should be returned - plays out, with the Conservatives determined to hold onto the money.

And then there is Diane Abbott. A pioneer MP, the first black woman elected to the Commons, who endures a vast amount of vile abuse which has been turbo-charged in the era of social media.

It is nearly a year since she was slung out of the Parliamentary Labour Party over remarks Sir Keir Starmer called antisemitic - and for which she apologised.

The Labour Party has spent 11 months investigating a letter to a newspaper she wrote that ran to a handful of sentences.

An alleged victim of racism, accused of racism herself.

What all of this amounts to is a case study in how society in the 2020s is wrestling with these giant concepts: belonging, identity, lived experience, heritage, language, labels, offence.

And how are we collectively wrestling with all of this?

Deeply awkwardly.

Related topics

- Published12 March 2024

- Published12 February 2024