Will David Cameron's EU child-benefit plan work?

- Published

It is not quite the pledge he made in his manifesto, but is David Cameron's compromise on paying child benefit to EU migrants workable?

The Conservatives won power promising: "If an EU migrant's child is living abroad, then they should receive no child benefit".

The letter from EU President Donald Tusk, setting out a possible new deal for the UK, says something rather different - such benefits could be indexed "to the standard of living in the member state where the child resides".

Rather than "no child benefit", EU migrants from poorer countries would receive less child benefit.

Opponents of the Tusk deal have been quick to suggest even this negotiated position is impractical.

So could it work?

There are approximately 2.4 million EU migrants living in the UK - but less than 1% of them are receiving child benefit for children back in their homeland.

Revenue & Customs suggests about 20,000 EU nationals receive the payment in respect of 34,000 children in their country of origin at an estimated cost of about £30m.

Most of those payments are for children resident in Poland, but several thousand Irish and French citizens resident in the UK also receive UK child benefit payments for children residing elsewhere.

It is a situation many regard as unfair.

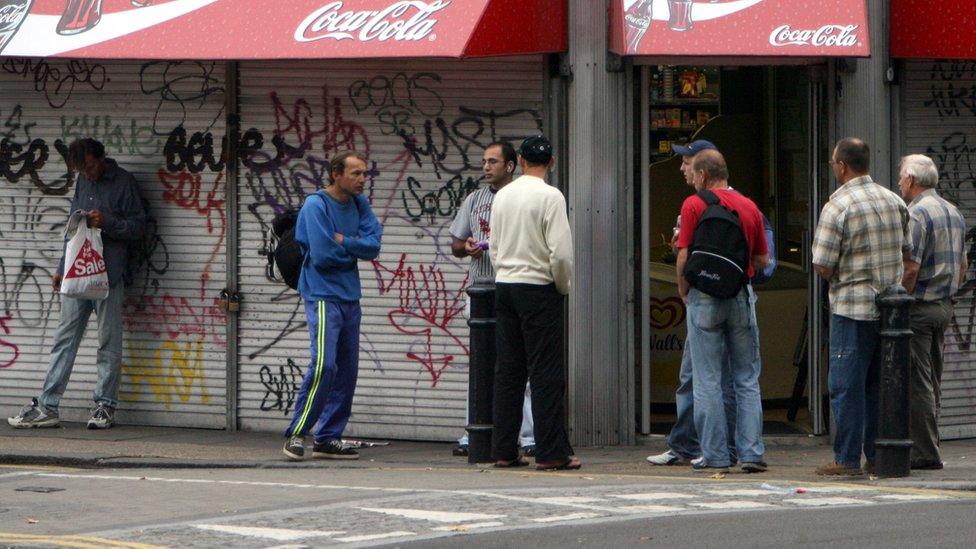

Some Polish workers receive the benefit to send back home

However, simply stopping the benefit altogether has proved tricky because it breaches a fundamental principle of the European Union - that EU citizens should have the same access to social protection as others in the country where they are living and working.

What makes child benefit unique among welfare payments is the recipient of the money - the adult EU migrant - can be in one country while the dependent is in another.

So the solution proposed is that "equal access" takes into account the living standard of the country where the child resides.

We do not yet know the details, but it is likely that average or "median" incomes could be used as a measure for living standards in each member state.

In the UK, child benefit for the first child is £20.70 a week - roughly 5% of the weekly median income.

That 5% figure could be used to calculate the payment in each EU state, based on its own median income.

In Romania, for example, rather than £20.70, the rate based on Romanian average incomes might be about £3.50.

A similar figure could be derived for each EU member state and the payments adjusted accordingly.

Almost all would be lower - but some single-market countries, such as Luxembourg, might expect a higher rate to reflect their higher living standards.

There have been suggestions having many different rates for child benefit would give government computers the collywobbles.

However, HMRC (which administers child benefit) and the Department for Work and Pensions already complete millions of complex international welfare transactions every year.

EU or EEA (European Economic Area) citizens living in the UK fill out a detailed form before they can claim benefits.

Sometimes, their work and social security history requires money transfers between countries to reflect residency in different parts of the EU.

Experts say it would be feasible and, arguably, fairer to introduce such a system.

But it would not make a massive difference to Britain's welfare bill.

For every £350 the UK spends on child benefit, the proposal would save something like 99p.