EU referendum: Will anyone read £9m government leaflet?

- Published

Haven't they heard of the internet?

One of the most shocking aspects of the government's decision to spend £9m on a campaign to promote Britain's EU membership - judging by social media reaction - is that it is based around leafleting.

Leaflets seem like a staggeringly inefficient and low rent way of getting a message out in today's networked world.

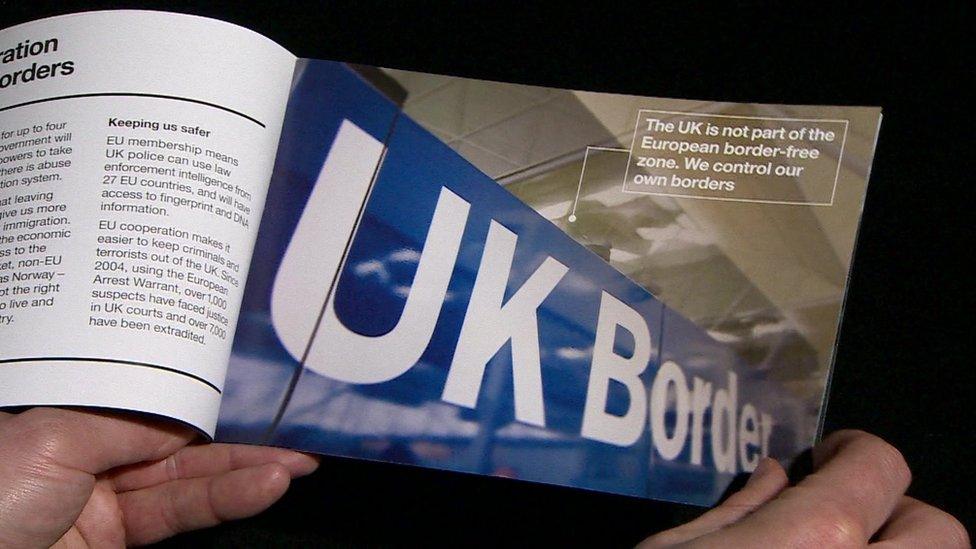

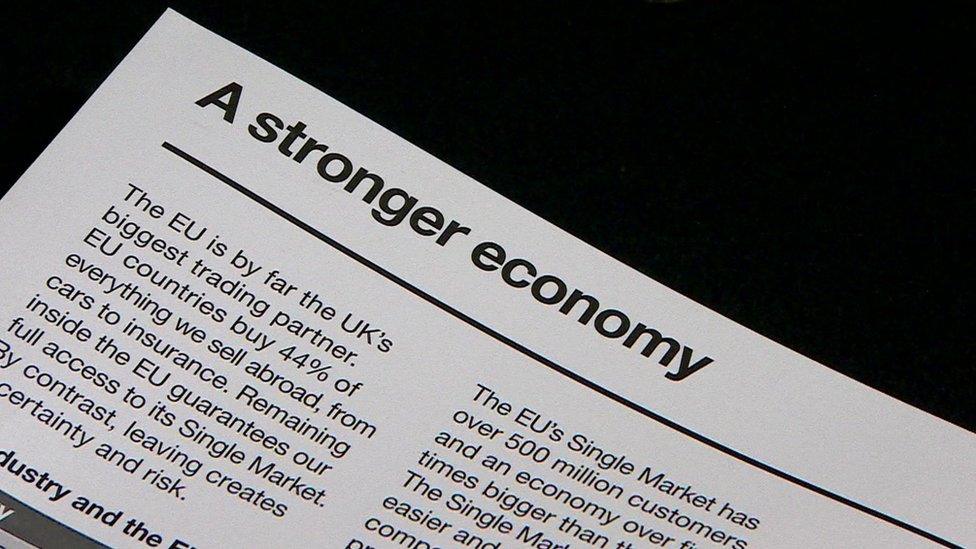

Even a 16-page glossy brochure, of the kind produced by the government, has a very "old school" feel about it.

Most of them will probably go straight in the bin, along with take-away flyers and credit card offers, say critics.

'Money well spent'

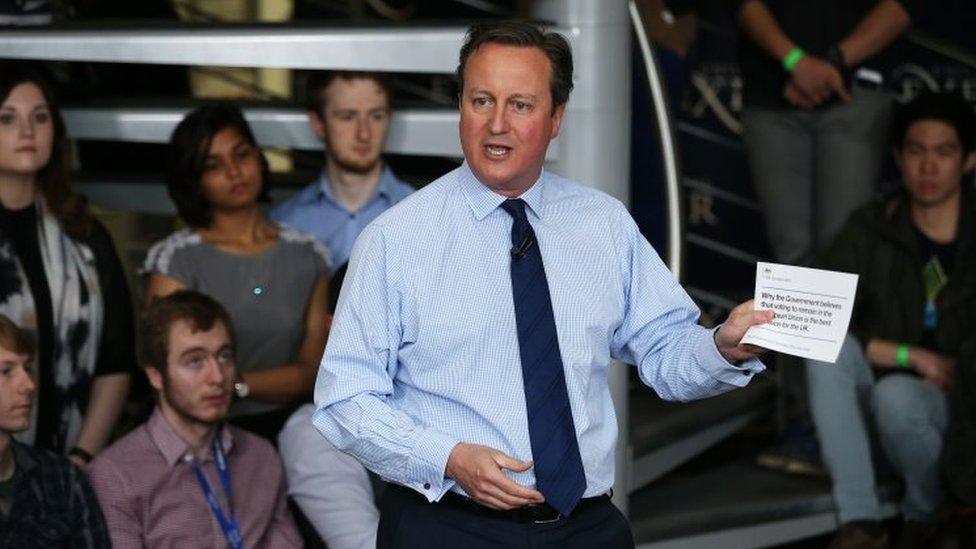

But David Cameron must feel that enough people will take a look at what the government has got to say to make it worth their while.

He has insisted the £9m campaign is "money well spent" - a little premature perhaps, given that we don't know the outcome of the referendum yet.

The leaflet will be sent to 27 million homes

In fact, both sides in the debate will be entitled to a free mailshot once the official campaign period gets under way.

What is causing so much controversy is that the government would not have been allowed to spend £9m on leaflets during the campaign, due to spending rules.

So why is everyone so desperate to pepper the country with unread pamphlets?

About a third of the £9m will be spent on an online and social media campaign - but printed material is still where it is at, says Philip Cowley, professor of politics at Queen Mary University of London.

"Political parties would not spend millions of pounds each election putting this stuff out if it didn't work.

"It's still the main mechanism by which voters hear from political organisations. It dwarfs every other form of contact."

'Poor third'

A face-to-face chat on the doorstep was still the most effective method of converting voters to your cause, he told BBC Radio 4's The World at One, but that was time-consuming, so mailing out leaflets was a "cheap" and "relatively easy" alternative.

Social media, he added, came a "poor third" as a tool of persuasion.

The government makes its case for staying in the EU

Leaflets reach the silent majority of people who are not glued to their smart phones day and night, particularly older people who tend to vote in large numbers and could swing the referendum in a close contest.

Another major advantage of mailshots over social media is that your claims are not immediately shot down and ridiculed by your opponents.

The government's EU brochure leaflet is available online, where the world can pick it apart.

But when you retrieve it from your doorstep, and take a glance at its contents on the short journey to the kitchen bin, your letterbox will not start spewing out spoof versions of it and angry rebuttals. Many of which will be more interesting than the original and a lot funnier. Unlike on social media.

Few facts

The government has attempted to justify its campaign by saying people are hungry for facts about the EU referendum. We know from our own inbox at the BBC how true this is.

The problem is that there are very few facts. Just about everything in the EU referendum debate is contestable, as soon as one side produces a "fact", the other side challenges it with a contradictory "fact".

That is because much of it is based on hypothetical scenarios. What would happen if the UK left the EU, what would happen if it remained? No wonder people say they are confused.

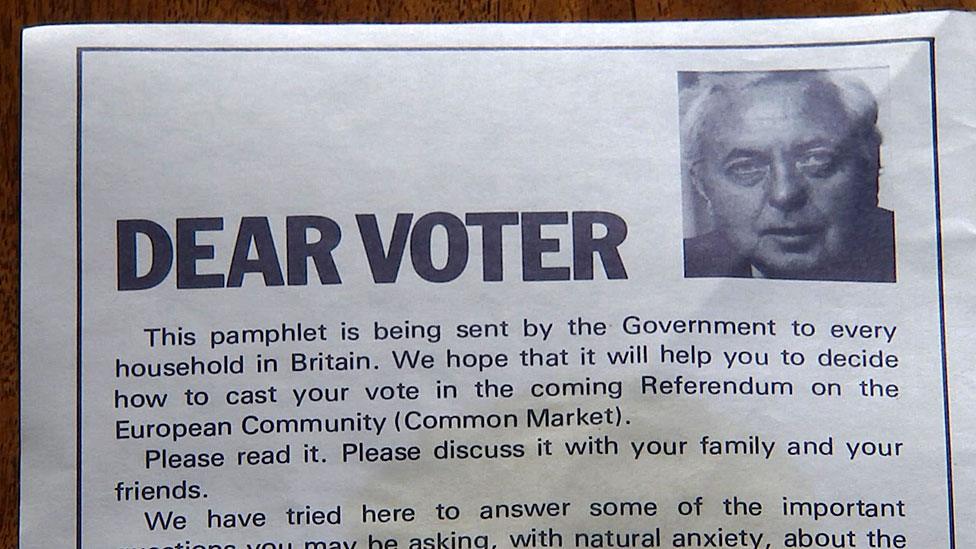

Harold Wilson sent a leaflet to voters in the 1975 referendum

The leaflet is a way for the government to cut through that. Leave campaigners are also sending out leaflets setting out the "facts" about Britain and the EU, although theirs will not be funded by the taxpayer.

The other justification ministers have used for their campaign is that there is a precedent for it. Harold Wilson's Labour government also sent out a leaflet to every household setting out the case for staying in the "common market", as the EU was then known.

The arguments made in Wilson's document, ahead of the 1975 EU referendum, have a very familiar ring to them.

But one crucial difference is that Mr Wilson himself is right there in the leaflet, making his personal recommendation to the country.

David Cameron is more than happy to do that when he is facing an audience at a Q&A session.

But his face is nowhere to be seen in the government brochure.

- Published7 April 2016

- Published26 May 2016

- Published7 April 2016

- Published9 September 2015

- Published8 September 2015

- Published2 September 2015