EU Referendum: Don't discount raw emotion

- Published

Campaigners have been struggling to get their message across in the early stages

American generals like to talk about "preparing the battlefield". And so it has been with the EU referendum campaign.

There have already been eight weeks of skirmishes but Friday is the curtain-raiser on the official EU referendum campaign.

That still leaves a longer period before voting than a general election. And the campaign is unlikely to catch fire until May when other polls are out of the way - mayoral/local contests and elections for the Scottish Parliament, Welsh Assembly and Northern Ireland Assembly. (For more on those elections, see our guide.)

What the opening rounds of the referendum campaign have been about so far is testing lines and arguments and trying to embed a narrative in the minds of the voters. The lesson of the Scottish referendum was "don't leave it until the final weeks".

This initial period has only confirmed what many continental Europeans regard as "Britain's eternal ambiguity towards Europe".

One French paper opined a couple of years back that "the British have only ever been interested in the single market and the rest of the European project leaves them indifferent".

It is not entirely true, but many of the initial debates revolve around a cost-benefit analysis; how much do we put in and what do we get out.

One commentator described it as a "bean-counting" referendum. You certainly don't hear much about the vision of the European project.

It is clear that the Remain campaign believes its strongest card is the economy and risk.

David Cameron has warned of an "economic shock", external from leaving the EU. All kinds of figures have been used to forecast the hit to UK living standards - perhaps by as much as 10%, suggests one European research institute.

David Cameron has warned of an economic shock from Brexit

The Remain side points out that when Boris Johnson declared for the Leave campaign the pound had one of its steepest falls since October 2009. Already uncertainty has knocked 0.3% off growth forecasts.

At risk, they argue, is not just sterling but foreign investment and the UK's balance of payments. And the UK will have to renegotiate more than 100 international trade and investment agreements.

So on to the Remain stage are summoned various business titans, American bankers, European business organisations and some of the heads of mighty European companies. All with the same message: "risk".

And this week the IMF, one of the heavier guns, has warned of "severe regional and global damage" - a risk not just to the UK but the world economy. The pulpit of the White House will shortly be deployed with a similar message.

Project fear

The Leave campaign responds to all this as "project fear".

Initially Leavers were repeatedly asked what life would be like after a British exit from the EU.

After flirting with the Swiss, Norwegian or Canadian model, external they, too, now talk more about risk.

For them the real risk is staying in an unreformed EU that they depict as the slow-growth region of the world economy.

Boris Johnson has generated much publicity for the Leave campaign

Dr Gerard Lyons, chief economic adviser to Mayor Boris Johnson, says: "The economies that will succeed need to be flexible, adaptable and control their own destiny.", external

Leave campaigners concede there might be some short-term pain but in the longer run they predict benefits from being outside the EU.

Yes, trade agreements would have to be renegotiated, but who wouldn't want to trade with the world's fifth largest economy?

The business community, they argue, is not of one mind and the IMF misjudged the impact of austerity on Greece.

Many of the claims, counter-claims and warnings from both sides are hard to assess.

For example, it was asserted, external that "leaving the EU would mean deep funding cuts for the NHS". Not long after, another group argued that leaving could free up funds that could be injected into the health service.

In the campaign so far what is rarely referred to is the deal that David Cameron returned with from Brussels in February. "Red cards", "emergency brakes" and release from "ever closer union" scarcely get a mention.

EU reform deal: What Cameron wanted and what he got

EU deal: What will it mean for Cameron at home and abroad?

The Leave campaign has decided to base its pitch on the ideal of control, of regaining control of the British economy, of borders (although the UK is not in Schengen) and of sovereignty.

It is an appeal to the gut, and the heart. The Remain campaign understands that passion as much as facts will determine the outcome.

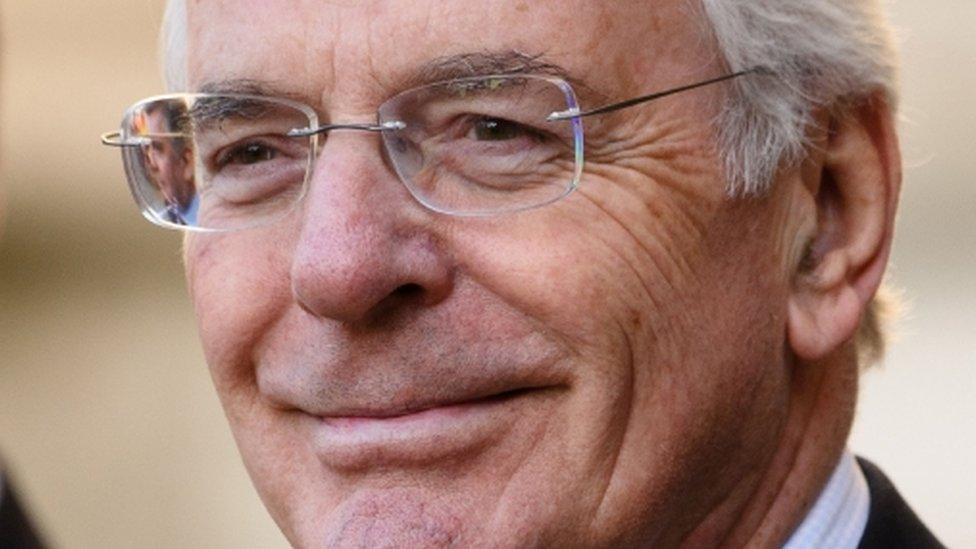

Sir John Major has warned of the possibility of emotion trumping reality

The former Prime Minister Sir John Major said, external: "The underlying mantra of the Out campaign is - and I use their words - 'I want my country back'. It is an emotional appeal but a bogus one. If emotion trumps over reality, we will lose power, prestige, security and some of our future well-being."

On Tuesday this week the former Foreign Secretary David Miliband called on those arguing for Britain to remain in the EU not to "cede passion or patriotism to the other side"., external

The chairman of the think tank Open Europe, Lord Leach of Fairford, said: "Voters are little better informed about what the future might look like inside or outside the EU. Brexit will not be an economic disaster and it will not be a utopia. There are tough choices involved in Brexit - nothing comes for free. Withdrawal from the EU is likely to result in an initial economic cost but Britain can prosper if it takes a liberal approach to trade, immigration and regulation post-Brexit."

And here's the problem. So much of this for the voters will be difficult to quantify and to weigh the risks and opportunities.

David Miliband said the Remain campaign must be as passionate as its opponents

Mujtaba Rahman, from the Eurasia group, says: "If Cameron's team is not able to win the economic argument - something they have been heavily focused on over the last eight weeks - they are unlikely to win the vote."

Some people tell me they expect a sterling moment when a poll triggers a further slide in the currency or a wobble on the financial markets - a development that could influence the vote.

But the Leave campaign also waits on events - a possible deepening of the European refugee crisis; a further bruising of the reputation of the prime minister; or the suspicion of elites that has been a feature of recent European polls.

The Remain campaign believes that ultimately voters won't take risks with the economy; they'll stick with the status quo. The Leave campaign believes it can sell the promise of a UK free from EU control.

Significant effort is going into establishing facts and debunking myths. But passion will be a factor in the outcome of a referendum which must judge the future.

- Published13 April 2016

- Published11 March 2016

- Published27 February 2016

- Published30 December 2020

- Published16 May 2016

- Published26 May 2016