Can Farage's breezy EU campaign win over floating voters?

- Published

Welcome aboard the top deck of an open top Daimler Fleet Line double decker.

A jalopy of such vintage, I'm told, Torvill and Dean used it for a victory parade in Nottingham in 1984. And it was in its second decade then.

In an era of airtight political choreography, this is a campaign that's sufficiently breezy that the party leader shouts "duck" on the upper deck as we all get whacked by branches when the bus goes under some trees.

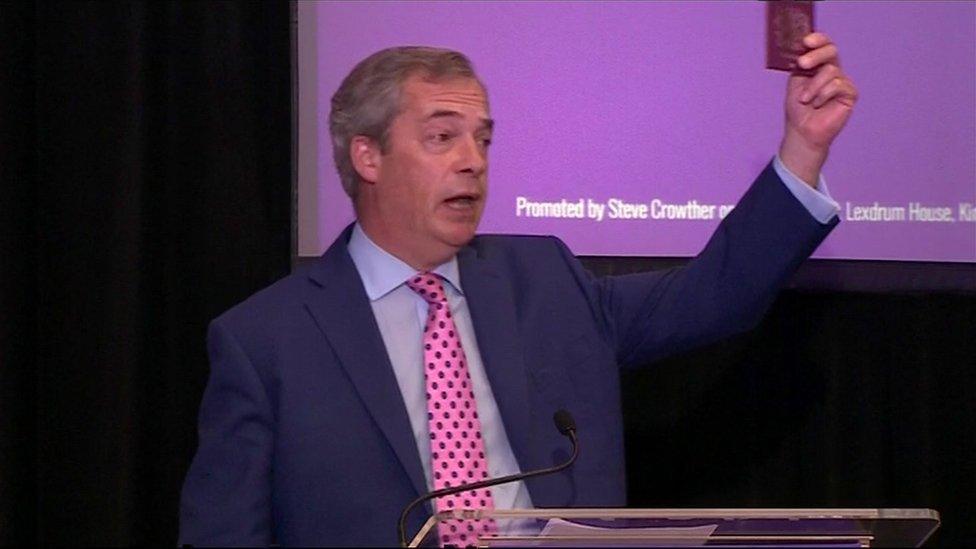

Think what you like about the UKIP leader Nigel Farage, but two things from this vantage point seem indisputable. This referendum is happening because of the impact he's had on British politics.

And who else at Westminster is up for the kind of campaigning he does?

Arriving in Chapeltown, just north of Sheffield, the loudspeakers gaffer taped onto the upper deck are turned on. Eager members of the small Team Farage are instructed to cling on to said speakers, such is the fear that gravity might triumph over them.

The music to The Great Escape pumps out, to a Farage chuckle; a joke the veteran MEP can't resist.

The response as the bus slows is binary: from the Anglo Saxon unbroadcastable insult, hollered with gusto, to the thumbs up and smile from the nonagenarian woman at the bus stop.

Persuasive or toxic?

Pulling up outside the Wagon and Horses, Mr Farage is the unlikely voice of temporary prohibition. It's just gone 10am and he had been after a coffee; some of his activists were necking lager half an hour earlier.

He leaps off the bus and starts chatting. Sure, these affairs attract the converted, the committed, the convinced. Even the evangelical.

Bits of slogan-emblazoned cardboard aloft, some approach him as if Bono or Bieber have rolled up. Kisses, autographs, all the rest of it.

But he has a crack too at passers by, the unconvinced, the unconverted, but persuadable. And one or two who have no intention of being persuaded at all. Mr Farage appears to be attempting to take on the crater-sized criticism screamed at him by his opponents also wanting the UK to vote to leave the EU.

Their critique is simple: he can motivate those who agree with him, but he's toxic amongst those who don't, and don't yet. The big question is this: given his binary appeal, are they right? His argument is this: look how many people I've won over so far.

They argue this is a race to get half of those who vote, plus one more. Can he convince those crucial floating voters?

Lunch, as you might have guessed, is at a pub. High on Saddleworth Moor, the Rams Head flies a St George's flag in the car park.

His persuading and charming, arguing and chatting, continues with whoever he meets. By two o'clock we are back on the vintage bus.

Whatever you do, don't ask for the wifi code or where the toilet is. A corkscrew appears. Briefly entertaining the idea that, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang like, it might be to get the charabanc going again, I ask what it's for.

Rioja an' roll

The Rioja appears. After all, we are half an hour down the M62 away from the next campaign stop in Bolton.

So let's be clear: you might have noticed this was an entertaining, engaging and refreshing day on the campaign trail. Refreshing, indeed, in all sorts of ways.

But here are the big questions: Does Nigel Farage change minds among the unconvinced to win a referendum? Or do too many people simply not like him?

It's a massive unanswered question. Can an approach to politics - as different as his is - actually lead it to the very highest success?

Can a man who has turbo charged an outfit from a dusty room in the London School of Economics into a major player in British politics, actually achieve the only thing he ever set out to do - get the UK out of the EU?

And, afterwards, whether win or lose, what on earth does he do next?

- Published17 May 2016

- Published29 April 2016