EU referendum: Can Leave win in the Glasgow shipyards?

- Published

Workers at the Clyde shipyards believe domestic policy will decide their future

The shipyards of the River Clyde were the engine of empire. They built whole navies, and liners that sailed the seven seas. And most of them have gone.

So when you talk of the European referendum here - about jobs in the old industries, and investment in the future - where do people believe their interest lies?

I found scepticism about the arguments on both sides.

To the older generation here in Glasgow, the Clyde isn't the river they once knew. You would have seen cranes and gantries filling the sky, all the way from the city westwards to the sea.

James Naughtie delves into the history of Glasgow shipbuilding with Dr Tony Pollard at the university archive

But the work has dwindled; a new industrial revolution has taken it away. A whole iron landscape has gone.

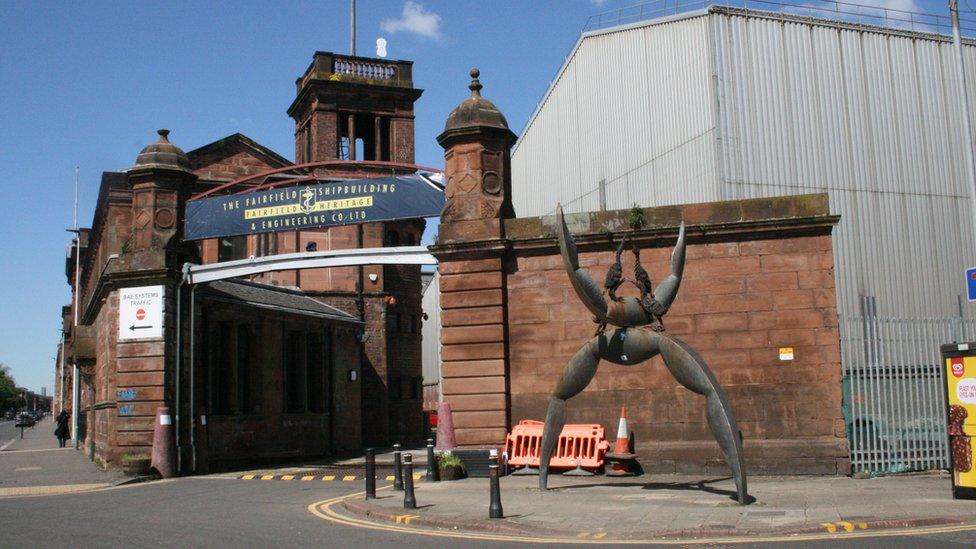

Sitting near the old Fairfield yard in Govan, now run by BAE Systems, I found workers who were broadly sympathetic to EU membership but who believed their livelihoods would, in the end, be decided at home.

John Brown - and what a name to carry on Clydeside, an echo of one of the great yards - told me that it would be in Whitehall (and to some extent in Edinburgh) that an industrial strategy would be built. If government wanted to retain a shipbuilding industry - as the French and Germans had done - they'd make it happen.

John Brown has an internationalist outlook

But that didn't mean he wanted to vote Leave. He was of a generation that enjoyed travelling to Europe and he cited his own family as evidence of an internationalist outlook.

"I'm married to a Bengali Scot. My son is going out with a Kurdish refugee." The world had changed, and he wouldn't want it to turn back.

His view touches on one of the characteristics of this referendum campaign. In Scotland generally, the Leave side is having a tougher time than south of the border.

The all-conquering SNP is campaigning vigorously for Remain and the Conservatives - now the second party in the Holyrood parliament - have a smaller Leave faction than their counterparts in England.

Do Scots really feel more positive about the EU?

EU referendum: Polls reveal divided nation

UK's EU referendum: All you need to know

The polls tell a consistent story: Scotland is leaning clearly to Remain.

You can sense part of the reason for that in Govan.

One referendum enough?

The men I spoke to across the yard where they are still waiting for the start of work on a Type 26 frigate for the Royal Navy - promised in 2014 just before the Scottish independence referendum and delayed until at least next year - don't see the decision on EU membership as the most important one for them.

If the government wants a shipbuilding industry, there will be work - EU rules or not.

And as for the Leave argument that new markets would open up, they say there is no magic formula for dealing with the problem of what has been moving steadily away from Europe to East Asia for the last 50 years.

The original plan to order 13 of the new Type 26 frigates was downgraded to eight in last year's defence review

Most striking of all is the contrast in the mood compared with the Scottish referendum in 2014, when this place was alive with argument.

That vote, you will remember, produced a turnout of around 85% across Scotland, an astonishing figure.

The reason was that the debate gripped everyone. By polling day many people said they were fed up - have you ever known an election when that wasn't true? - but most of them took the trouble to make their choice.

Fairfield shipyard once employed more than 3,000 people

This time it's different. You can find passion on both sides, but in Scotland as a whole there is none of the feeling of a "once in a generation" vote that was so obvious in 2014.

Maybe one referendum was enough for some people.

It is also true that although the immigration argument plays a part, it seems less potent here.

Who knows what may change in the next three weeks or so, but as things stand, Scotland is more likely to say Remain than Leave.

And were England to say Leave, another chapter opens. But that is a story for another day.