Could leaving the EU make British chocolate taste bad?

- Published

The British are a nation of chocolate lovers but could leaving the EU make our best-loved bars taste bad?

How many British people have bought a bar of chocolate on holiday somewhere outside Europe and been surprised at how different it tastes?

EU rules demand chocolate contains 30% cocoa - compared with only 10% in the US - and that is what makes British chocolate so delicious, says emeritus Professor Mike Gordon.

"A high cocoa content is important to give it a good flavour, external," said the retired food and nutritional sciences lecturer at the University of Reading.

"I remember having a Hershey bar in the 1960s which was pretty poor quality, but I've not tried US chocolate for many years," he said.

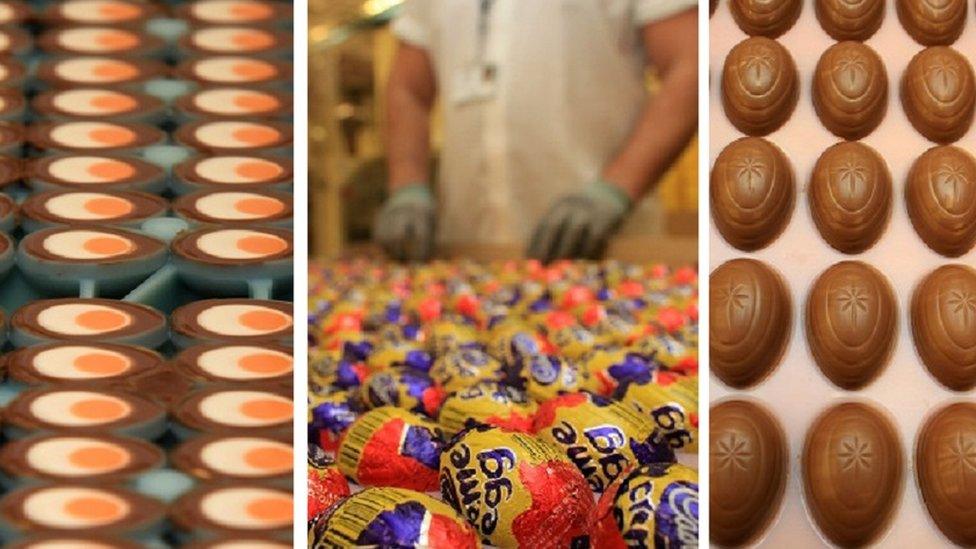

Kraft Foods bought Cadbury in 2010 and its global snacks business under the name of Mondelez International

The quintessentially British Cadbury's chocolate has been made at the Bournville factory in Birmingham since 1905, external.

The regal-looking purple-wrapped bars contain up to 5% vegetable fats under EU law but it is not added to the recipe across the pond.

So if the UK left the EU, could Cadbury's American owner change the recipe to suit its own tastes or even take production away from Britain altogether?

Snack giant Mondelez International, which owns Kraft and took over Cadbury in 2010, said it was watching the EU referendum campaign closely.

"As a business that sells products across the EU, we look forward to having clarity on the UK's role within Europe so that we can have certainty and make long term plans for our business," a spokesman said.

Cadbury's owners Mondelez said Bournville was the "best place in the world" to make bars such as Dairy Milk

But there were no plans to move production out of Bournville, which he called "the heart and home of Cadbury".

In 2014, Mondelez invested £75m to upgrade lines at the factory, which it hailed as "the best place in the world" to make bars such as Dairy Milk.

But the company remained tight-lipped when pressed on the possibility of recipe changes in the event of the "leave" vote winning the EU referendum on 23 June.

"We can't say anything else at this point," the spokesman said.

Changes to the nation's favourite chocolate brands do not go unnoticed.

There was online outcry last year when the chocolate shell of Cadbury's Creme Eggs was changed from Dairy Milk to "standard, traditional Cadbury milk chocolate".

Fans of Cadbury's creme eggs noticed the chocolate shell tasted different after American-owned Kraft took over the brand

Fans of the Fruit and Nut bar were similarly unhappy a few months later when sultanas were added to the recipe along with raisins.

And the new curved shape of Dairy Milk, which saw the bar shrink from 49g to 45g, sparked a debate on whether it changed the taste.

"The big confectionery companies go to great lengths to ensure consistent flavours at the lowest price, so the chances of noticing any change [if Britain left the EU] are very low," said chocolate expert Dom Ramsey.

Mr Ramsey runs a craft-chocolate making business in London and believes companies such as his would be hit hardest by leaving the EU.

"Smaller makers are more likely to be focused on quality, making it increasingly difficult to sell an already higher-priced product if things like import duties come into play," he said.

Does British chocolate really taste different from American chocolate?

American Sidhartha Nilakanta said US Cadbury's tasted "creamy" while the UK version was "just average"

Brits and Americans were united in spotting differences in taste between US and UK chocolate in BBC blind tests.

One British taster, Alexandra Dimsdale, described US Cadbury as having a "chemical fruity taste", UK Cadbury as "delicious and comforting" and Hershey's as "more oily".

Meanwhile, Sidhartha Nilakanta said the Cadbury made in his home country was "creamy and sticky", the UK version "just average" and Hershey's a "little chalky".

Hershey, which has the licence to make Cadbury products in the US, blocked the import of the UK version to protect its American brand but said that was nothing to do with differences in taste.

The ban led to Brits living across the Atlantic stockpiling their favourite bars before shops ran out.

Consumers are stocking up on Cadbury Chocolate while they still can

Another London-based chocolate consultant, Jennifer Earle, said the UK had a history of doing chocolate differently from the rest of Europe.

In 2000, the UK won a 27-year-battle, external to make its EU partners sell British chocolate made with up to 5% vegetable fats or up to 20% milk content, external across all member states.

"We've always had that exception and that's what people like over here so I don't think it would have much effect if we left the EU," she said.

Before the EU ruling "chocolate purist countries" Belgium, France, Italy, Spain, Luxembourg, Germany, Greece and Holland banned vegetable fats from their own and imported chocolate.

"Cocoa butter is the only fat that should be used in chocolate," says fellow purist Angus Thirlwell, who co-founded British high-end brand Hotel Chocolat.

Angus Thirlwell does not believe chocolate should be called chocolate if its largest ingredient is not cocoa

Mr Thirlwell's mantra is "more cocoa less sugar" and his milk chocolate contains a minimum of 40% cocoa.

He said two world wars and rationing were to blame for diminishing the cocoa content of British chocolate.

"There was a temptation that people had got used to that taste and sugar was 10 times cheaper than cocoa so British chocolate has never really recovered," he said.

"Historically the amount of cocoa in counter line chocolate has gone down and down and down and I can't see that bottom being reached yet.

"British chocolate brands have been taken over by American companies and they are increasingly pulled towards the orbit of American approach to chocolate."

Mr Thirlwell believes it is "unacceptable" for a bar to be called chocolate if the largest ingredient is not cocoa.

"It should be called candy," he said. "If we leave the EU perhaps Britain could create our own standards that are more rigorous."

So leaving the EU could allow British chocolate makers to break free from regulations and change their recipes.

But as a nation so passionate about our bars, with palates highly sensitive to change, it seems unlikely the chocolate manufacturers would want to leave a bad taste in our mouths.

- Published29 March 2013

- Published27 October 2014

- Published18 March 2015

- Published30 December 2020

- Published29 April 2016