Brexit: Key questions after Britain's vote to exit the EU

- Published

The vote sent shockwaves through the UK and Europe

The referendum that saw the UK vote to leave the EU has left confused waters in its frothy wake.

Here is a look at some of the current key questions surrounding the decision.

When is the UK leaving? Why hasn't it left yet?

People protested against Brexit in London in the week after the referendum

The referendum result did not automatically mean that the UK would leave the EU. In fact, the result of the vote is not even legally binding - for the UK to leave the EU, it has to formally invoke an agreement called Article 50, which is part of the Lisbon Treaty.

Once Article 50 has been invoked in a letter or a speech, the formal process of withdrawing from the EU can begin, at which point the UK has two years to negotiate its withdrawal with the other member states. Extricating the UK from the EU will be extremely complex, and the process could drag on for longer than that - no country has ever left the EU, so just how Article 50 works is untested.

On the morning the results came through, UK Prime Minister David Cameron, who backed Remain, unexpectedly told the country he would stand down by October and that he was leaving it to his successor to decide when to trigger Article 50.

Leave campaigners say they want informal discussions with the EU first, while foreign ministers of France and Germany have called for Article 50 to be triggered as soon as possible to avoid prolonging a period of uncertainty.

There have been questions whether the process can be stopped, and a petition to call a second referendum gathered millions of signatures in days, but a second vote is unlikely.

As the BBC's legal expert Clive Colman says it "seems impossible to see a legal challenge stopping the great democratic juggernaut now chuntering towards the EU's departure gate".

Ok, so who's in charge of making the decision?

David Cameron has announced he will resign

Of Brexit? Well, nobody really knows.

It looked like it was going to be former Mayor of London Boris Johnson, long-since tipped to be the next UK prime minister. He was a late convert to the Leave cause, but is hugely popular and would have been expected to implement Brexit sharpish.

But in a shocking development, his Leave campaign sidekick Michael Gove threw his hat in the ring for the Conservative Party leadership, because Mr Johnson was "not capable of leading the party and the country in the way that I would have hoped".

Then, Mr Johnson pulled out during the very speech that was meant to kick-start his campaign.

Newspapers compared the fallout between Mr Gove and Mr Johnson to a Shakespearean play or Game of Thrones, saying Mr Johnson had been "Brexecuted".

After all that, Mr Gove is not even the favourite - the feeling is that he may have overplayed his political hand and damaged his chances by turning so abruptly on his former mate.

Of the five candidates, the front-runner is the most senior woman in the House of Commons, Theresa May, who has been home secretary since 2010.

Surprisingly, she's one of the two leadership contenders who backed Remain, although both of them say the referendum result must be honoured. "Brexit means Brexit," Mrs May said.

Theresa May is the frontrunner to be the next UK prime minister

For politics-watchers in the UK, it has been an extraordinary week, sometimes bordering on the ridiculous, external.

"A country renowned for its political and legal stability is descending into chaos," wrote the New York Times.

And we haven't even started telling you about the Labour party yet.

What's happening with the opposition?

The Labour party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, is facing open insurrection from his MPs

Many Labour MPs believe their leader Jeremy Corbyn failed to mobilise Labour voters to support the Remain campaign. They fear he would fail to win if a snap general election was called.

And so, one after the other, more than a dozen shadow cabinet members resigned, leaving Mr Corbyn facing an open insurrection.

As if that wasn't enough, his MPs then voted 172-40 to declare no confidence in him.

Even Mr Cameron seemed exasperated. In even rowdier scenes than usual at Westminster's House of Commons, the prime minister told him: "For heavens sake, man, go!"

Still, Mr Corbyn refuses to resign, saying it would be a betrayal of the party's grassroots members whose still support him.

But it's not over. Mr Corbyn is expected to face a formal leadership challenge very soon.

Is the UK economy falling apart?

The value of the pound took a hit after the referendum results came in

Not quite, but here too it has been an eventful week.

The Chancellor, George Osborne, has abandoned his target to restore government finances to a surplus by 2020, saying that the economy is showing "clear signs" of shock following the vote.

Credit agencies have cut their ratings for the UK and for the EU as a whole.

Markets are not fans of uncertainty and the UK's FTSE 100 index plummeted on the morning after the referendum. It has since rallied, but as the uncertainty continues the market is likely to continue to vary.

The value of the pound against the dollar dropped to a 31-year low, meaning UK holidaymakers were buying substantially less cash for their travel wallets than they might have expected before hand.

The low value of the pound will adversely affect imports too, and because global oil prices are decided in dollars, prices at UK petrol pumps are likely to go up.

The Bank of England says the growth will be slower than expected next year and stimulus measures may be required.

That said, it will take longer to tell whether house prices will be affected and how the manufacturing and financial service industries will respond.

Is the Leave campaign abandoning its pledges?

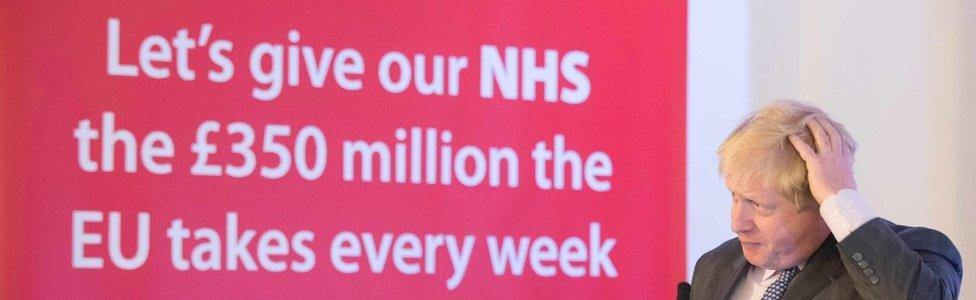

Questions surround whether Leave campaigners can deliver their promises

Within hours of the results, the Leave campaign was being accused of rowing back on several of its key campaign pledges.

Among them, the bold claim that the UK would take back £350m donated to the EU every week and spend it on the NHS. The pledge was widely criticised during the campaign by many who pointed out that £350m is the UK's gross contribution, and that it receives vast sums of money back from the EU.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies calculated during the campaign that of the £360m the UK sent to the EU weekly in 2014, the net contribution was just £109m.

Key Leave campaigners including Nigel Farage, Boris Johnson and Ian Duncan Smith have since distanced themselves from the £350m promise, with Mr Duncan Smith claiming it was a "possibility" rather than a pledge.

Other key campaign pledges have been called into question. Leave promised to "take back control of Britain's borders" and reduce immigration, but several key Leave campaigners have since suggested that the UK may need to accept freedom of movement in order to have access to the single market.

"A lot of things were said in advance of this referendum that we might want to think about again," said Leave campaigner and former Conservative minister Liam Fox.

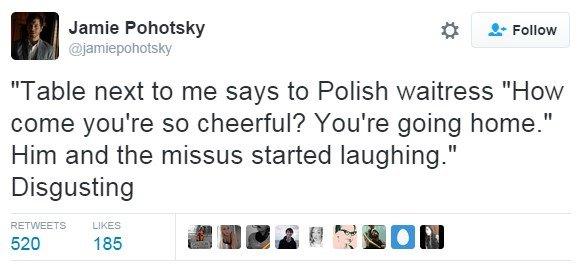

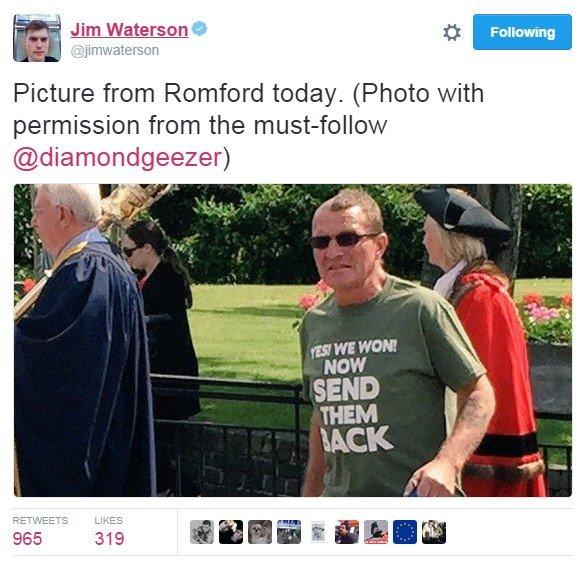

Has the Leave campaign encouraged racism?

There are no official statistics, but there has been a significant number of reports on social media of racist abuse linked to the Leave win. Some high-profile incidents have been verified by police.

In Hammersmith, west London, on Sunday, suspected racist graffiti was painted on the front entrance of the Polish Social and Cultural Association.

And in Cambridgeshire, police are investigating laminated cards that were posted through letterboxes and left outside a school, which read: "Leave the EU/No more Polish vermin" in both English and Polish.

There has been a stream of reports on social media of people hurling abuse at others they assume to be immigrants. The Leave campaign has faced accusations that it encouraged hostility towards immigrants.

Could Brexit break up the UK?

Scotland voted to stay in the EU

Unlike England and Wales, Scotland voted overwhelmingly to remain in the EU, and Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon says it is "democratically unacceptable" for the country to be taken out of the union against its will.

A second independence referendum for the country is now "highly likely", she says, and recent polls suggest roughly 60% of Scots are now in favour of leaving the UK in order to remain in the EU.

One constitutional expert has suggested Scotland could go further under its law and effectively veto Brexit, although others have dismissed this idea as extreme.

Ms Sturgeon visited Brussels for a series of talks with senior EU officials in the week after the referendum, but the Spanish prime minister and French president both said they were opposed to Scotland negotiating EU membership outside the UK.

Northern Ireland also voted in favour of remaining, and Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness, of the Sinn Fein party, has called for a referendum on reuniting it with the Republic of Ireland, which is outside the UK and remains in the EU.

But the Westminster-based Northern Ireland Secretary Theresa Villiers has ruled that out, saying there was no legal framework for a vote to be called. Ms Villiers is a Conservative Party MP and campaigned for a Leave vote.

There is uncertainty over whether a so-called "hard border" would have to be put in place between the North and the South if the North exits the EU.

- Published19 June 2016

- Published27 June 2016

- Published27 June 2016

- Published26 June 2016

- Published25 June 2016

- Published26 June 2016

- Published25 June 2016

- Published24 June 2016

- Published24 June 2016