Brexit bill: what happens next?

- Published

- comments

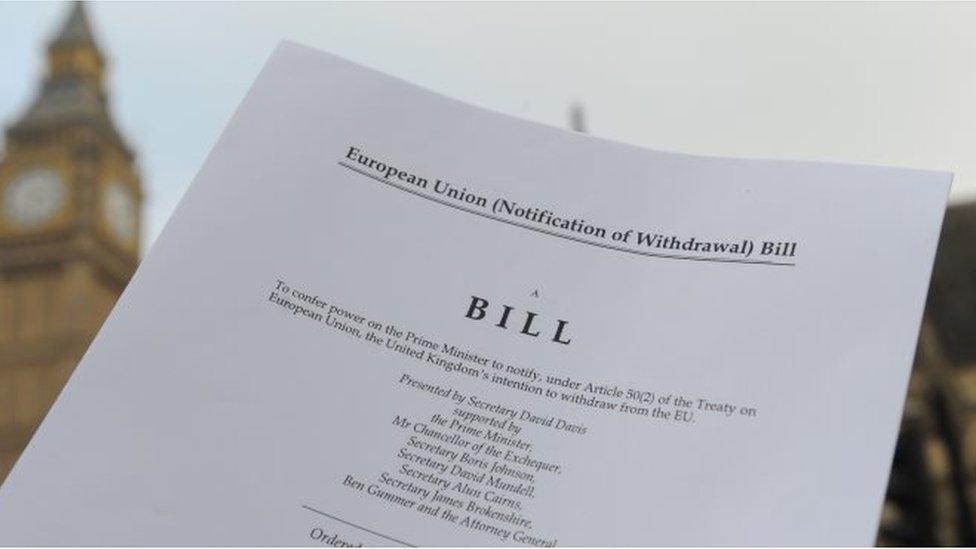

The game's afoot! And the thumping four to one Commons majority for the Brexit Bill (aka the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill) does not mean the government whips can now wrest on their laurels, confident that no-one will dare amend it.

Next week's three days of committee of the whole House, external threatens to be a far more serious and subtle test of their mettle - and also of the Deputy Speakers who will chair proceedings.

As I write, there were 114 new clauses proposed for the bill (it's only 137 words long, so no-one seems to be inclined to mess with its minimal wording).

These will be sifted to eliminate those which are "out of scope" - going beyond the purpose of the bill.

But it seems likely that there will be plenty left....

I'll deal with the actual subject matter in my regular blog on what's coming up in Parliament, but let's look at why this will pose a considerable strain on the whips (including Labour's) and the Chair.

What are the problems for the whips?

First, MPs who voted to back the principle of the bill at second reading can, perfectly reasonably, claim to have issues with the detail, or rather, detailed issues they want the bill to deal with.

And one reason for the number of proposals to add new clauses that have been raining down upon the bill is that some of those who want to make changes to it have been drafting and redrafting their wording to attract as much support as possible.

Here comes the science bit...concentrate!

The debate will be structured by topic - so on Monday from 3.30pm till 7pm, the House will look at parliamentary scrutiny issues - that's proposals to build in requirements for regular reports on particular issues, or for regular statements to the House, for example.

Within these subject headings, the amendments will be "grouped" under narrower headings, which will then be voted on.

And this rather tekky sounding process matters a lot to the parties, and the various MPs grouped around particular pro-Brexit and anti-Brexit standards, because the grouping determines how much chance they will have to make to put their particular points.

Each group will have a "lead amendment", which is automatically put to the House at the end of the timeslot.

This may mean shouts of Aye and No, with the Chair declaring a winner, or it may mean a full-scale division, with MPs filing into the lobbies to have their votes recorded. The choice of lead amendment gives automatic priority and prominence in debate - and the parties all want their moment in the spotlight, and they won't be happy if they feel they've been carved out.

This first part of the process is sorted out via the "usual channels": the behind-the-scenes negotiations between the parties' business managers.

But then comes the difficult bit - votes on amendments lower down the batting order are at the discretion of the Chair - the decision is made on a kind of real-time basis, informed by which amendments have been most commented on in debate….

The confidence in, and acceptance of, their rulings will not be enhanced by the thought that all three deputy speakers are casting covetous eyes on the succession to throne of King John Bercow (who is expected to step down in the next year or so); and that their rulings may end up being used in evidence against them.

And if the selection produces a result which means the official Opposition always have the lead amendment, then that puts the SNP and Lib Dems, not to mention any guerrilla groups of Remainers, rather at the mercy of the Chair.

Decisions about which amendments further down the group get called for "separate decision" are more seat-of-the-pants than science - so will the Chair make a calculation about the ones most likely to attract cross-party support? Or will they be more concerned just to hand them out between the parties, ignoring any backbench rebellions?

Even the order in which the amendments were put down matters - which is why there was a certain amount of jostling and argy-bargy at the Commons table, last Thursday, moments after MPs had approved a motion allowing amendments to be put down immediately, with pro-remain MPs and Labour whips pushing for priority.

So there will be a lot of tension as each "knife" (or end point in the section of debate) approaches.

Which amendments will get their 15 minutes of fame? Will it be the Tim Farron one? Or will it be the Ken Clarke/Anna Soubry one? Will the Joint Committee on Human Right's amendment on guaranteeing residence to EU citizens get called, or even selected? Will a more intellectually pure approach be adopted which rigorously tests each amendment to see if it genuinely raises a different point to one already decided? And how many "separate decisions" will the Chair allow?

All the players are conscious that pushing for too many votes will use up valuable time.

It is also worth remembering that any amendment that would incur a cost on the taxpayer is unselectable, because there is no money resolution authorising such expenditure - but, again, the application of this rule can be more art than science, but, for example, any amendment insisting directly on a second referendum is likely to fall foul of the lack of a money resolution.

And if, as is entirely possible, the bill is not amended in committee of the whole House, there is no need for a report stage, so the bill does not pass Go and proceeds directly to its third reading - so no report stage means no second bite at amendments.

And then the prize the government whips are hoping for; an un-amended bill, girded with vast Commons majorities, is far less likely to be tinkered with by Their Lordships, when they begin their consideration of it in the House of Lords, on 20 February.

- Published30 December 2020

- Published28 March 2017