Article 50: Is Whitehall ready for Brexit?

- Published

If you walk down Whitehall in central London, you cannot escape reminders of wars fought and empires run from this small district on the north bank of the Thames. There are memorials to the fallen, statues of field marshals and even a Turkish cannon captured in some long-forgotten conflict.

Yet the civil service that once gloried in its global administrative stretch is now the smallest it has been since World War Two. And with the government launching the British state on its greatest administrative, economic and legal reform since it committed the nation to total war in 1939, there is a simple question: is Whitehall up for Brexit?

"It's been a scramble but the ducks are in a row," one Cabinet minister told me confidently.

For the scale of the challenge is immense.

Thousands of civil servants to be mobilised and retasked, thousands of laws and regulations to be rewritten or rejected and thousands of people trained and employed to do the many things currently carried out by the European Union.

This endeavour is not only about the two years of initial negotiations with 27 EU member states that will shortly begin, it is also about the mammoth preparations the UK must make for leaving the EU whatever the outcome of the negotiations.

"The challenge of Brexit has few, if any, parallels in its complexity," says Sir Jeremy Heywood, the Cabinet Secretary. "Its full implications and impact on the political, economic and social life of the country... will probably only become clear from the perspective of future decades."

Sir Jeremy Heywood, the Cabinet Secretary, believes Brexit has "few, if any, parallels in its complexity"

Perhaps the greatest challenge the civil service has faced was its utter lack of preparation for the British people voting out in the referendum last June. They were expressly forbidden from drawing up any plans by David Cameron's administration and have been playing catch up ever since.

Ministers say the civil service has responded well, creating two new government departments from a standing start. The Department for Exiting the EU (DExEU) has something north of 320 staff, the Department for International Trade, several thousand.

Both departments, along with the Foreign Office, have been given an extra £400m by the Treasury over the next four years to pay for their work on Brexit. There were some initial turf wars but officials now say there is greater singularity of purpose.

Much work has been done analysing options, quantifying markets and assessing laws. Huge volumes of paper have been landing on DExEU desks looking at the impact of Brexit on every aspect of the economy.

The aim is to allow David Davis, the Secretary of State for Exiting the EU, to draw up an a la carte menu for the prime minister, setting out potential options and costs so that she can navigate the negotiations ahead.

For there is no doubt that these will be Theresa May's negotiations. The main negotiating team will include Mr Davis, his permanent secretary, Olly Robbins, and Sir Tim Barrow, the UK permanent representative to the EU.

Below them will be civil servants from all affected government departments, summoned in to work on specific "chapters" of the negotiations, on everything from fish to agriculture to financial services. They will be the team dealing with the European Commission negotiators on an almost daily basis.

Yet above them will be Mrs May who will have to drive the talks and make the big calls. But such is the size of the task that even the prime minister will struggle to retain her usual iron grip.

One minister told me: "This is the first big test to see if she can delegate. This is so big that No 10 cannot control it, they cannot be on top of all the detail."

Theresa May has made it clear that she will drive the UK's Brexit negotiations

Not all are so sanguine about the preparedness of Whitehall. The National Audit Office says in a new report that, while 1,000 new roles have been created in the civil service to deal with Brexit, a third remain unfilled and most of the new appointees have simply been transferred from other parts of government.

And the Institute for Government warns that departments such as the Home Office and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs are underfunded, cannot afford more staff and will be forced to drop non-Brexit work.

Other insiders warn that, although much work has been done setting out options, less thought has been devoted to how the negotiations will progress themselves and how the government should organise itself. Officials talk of not knowing precisely for what they are preparing because Downing Street refuses to reveal its negotiating plans.

The process, inevitably, will begin with negotiations about the negotiations. Who will talk to whom, about what and in what order? The UK government wants to discuss its divorce from the EU at the same time as its future trade relationship. The EU says the two issues must remain separate.

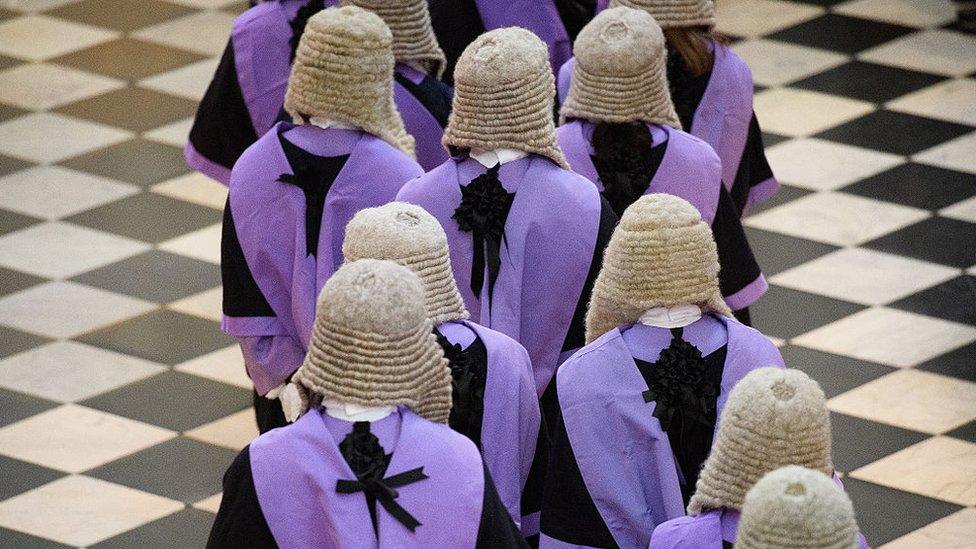

Unstitching the UK from EU laws will be an intricate process

Then will come the exit agreement itself. Much will be visceral and hard-fought. Protecting the rights of EU nationals in the UK and vice versa sounds easy as both sides say they want this to be resolved early on and want to keep the status quo. But the hugely complex detail will be hard to agree.

Yet sorting that out might be easy compared to agreeing how much money, if any, the UK will owe the EU when it leaves. The government says nothing, the EU is hinting at £50bn. And all this is before any negotiations about any future trade arrangement between the UK and the EU and any transitional process that may be needed.

While this will generate a huge amount of work for some in the civil service, many other officials will be focused instead on preparing the UK for leaving the EU come what may.

Much of this will focus on Westminster. There is the Great Repeal Bill to be written and passed through Parliament to ensure that all EU law is transferred automatically into UK law the moment we leave. The aim is to ensure there is no legal chaos and to allow Parliament all the time it needs gradually to unstitch the UK from four decades of EU legislation.

This will be a massive piece of legislative work that will require officials to re-examine huge swathes of UK law. They will have to decide which bits of EU law to return to Westminster and which bits are devolved, a tricky issue in light of Holyrood's demand for a second independence referendum. The Institute for Government warns there might be a need for further 15 separate Brexit Bills.

The UK will have to forge a new trade relationship with both the EU and the WTO

In the short term, there are a huge number of separate parliamentary inquiries into Brexit - 55 in all - being carried out by various committees of MPs and peers. Ministers have to reply to each one within 60 days and officials are struggling to meet that deadline.

Then there is the process of the UK re-establishing its status at the World Trade Organization (WTO), something that will be needed even if we get a new trade deal with the EU.

The government hopes to transfer its current EU tariff rates into a new UK-specific schedule of trade commitments. But such a "copy and paste" arrangement will be complicated and will almost certainly face challenge from other WTO members. UK diplomats in Geneva, where the WTO is based, have a hard job of reassurance ahead of them.

And then there is also the process of creating new organisations that will fill the gaps in our national life left as the EU tide ebbs from our shores. Officials will need to set up new customs and immigration systems, neither of which will be simple or easy.

So, as the phoney war ends with the triggering of Article 50, Whitehall is facing perhaps its greatest challenge in a generation.

- Published21 March 2017

- Published29 March 2017