Following Nelson Mandela from Natal to Glasgow

- Published

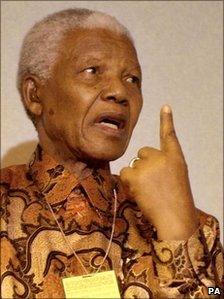

Former East Africa correspondent Colin Blane interviewed Nelson Mandela many times in the years after he was released from prison

Veteran BBC journalist Colin Blane first met Nelson Mandela when as a former Africa correspondent he covered South Africa's first elections after the end of apartheid. He met him again after he had returned to report on his native Scotland, towards which Mandela had great affection.

We waited in the morning sunshine outside the little schoolhouse in Natal, knowing that we were about to witness something truly historic.

The venue had been kept secret so there was no crowd of well-wishers.

A single ballot box had been placed on the veranda. We knew Nelson Mandela had already arrived.

Then he appeared. Mandela stood for a moment holding his folded ballot for the cameras; then he popped the paper in the box.

At 75, he was about to become president of South Africa, yet this was the first time in his long life he had ever been allowed to vote.

He raised his fist and smiled that broad, infectious smile.

There was a ripple of clapping and someone called out "Bravo".

This was a scene no-one could have imagined even a few years before.

That simple act of voting had taken the African National Congress 80 years of campaigning.

Twenty million others took part in South Africa's first non-racial elections, most of them voting for the first time.

I was there as a former BBC East Africa correspondent who had helped to cover the negotiations and the years of township violence on the road towards democracy.

My patch during the elections of 1994 was KwaZulu Natal, the province which was torn by the bloody rivalry between the ANC and the mainly Zula Inkatha Freedom Party.

Mandela could have chosen to vote anywhere from Cape Town to Soweto but he decided on an act of reconciliation in Natal - and so it fell to me to watch and describe what happened.

In the years after he came out of prison I met Mandela several times.

He and his colleagues were keenly aware of the support they had received during the bleak decades of apartheid and so his visits outside South Africa were highly symbolic.

Mandela went to Zambia, Tanzania, Ethiopia - all countries which had helped the ANC when others turned their backs. And remarkably, he went to Glasgow.

I saw him on those African visits and by the time he got to Glasgow, I was back there too, catching a few words outside the City Chambers as he arrived to accept a collection of honours from all over Britain.

His warmest praise was for Glasgow, for the support the city had given to him and his fellow prisoners.

"Whilst we were physically denied our freedom in the country of our birth, a city 6,000 miles away, and as renowned as Glasgow, refused to accept the legitimacy of the apartheid system and declared us to be free.

"It is for this reason that we respect, admire and above all, love you all."

Mandela shuffle

Outside the City Chambers, Nelson Mandela lit up the grey October day, joining the dancers on stage and wowing the crowd with his own Mandela shuffle.

That was not the end of Nelson Mandela's connection with Scotland, or indeed with Glasgow.

Mr Mandela visited Megrahi when he was in Barlinne prison

He became a key figure in the negotiations which brought the two Libyans accused of the Lockerbie bombing to trial at Camp Zeist in the Netherlands.

Mandela argued the men ought to be tried in a neutral country.

After Abdelbaset al-Megrahi was convicted and brought to Scotland, Mandela visited him in Barlinnie.

I was there when he told a packed press conference inside the prison he believed Megrahi should be allowed a fresh appeal and should be transferred to serve his sentence in a Muslim country.

Seven years on, Nelson Mandela wrote to the Scottish government backing the decision to release Megrahi on compassionate grounds.

Mandela was already an old man by the time he became president in 1994.

His children joked that he was too busy being Father of the Nation to be a father to them.

When Margaret Thatcher stood down as the UK's prime minister, months after his released from 27 years in prison in 1990, I went with a TV crew to seek Mandela's reaction.

Nelson Mandela thanks the people of Glasgow for their support during his imprisonment.

He was resting in his room and came down a short while later.

Ever the joker, he apologised for keeping us waiting and said with a twinkle in his eye: "When the BBC calls, everyone must come."

We wondered what he would say about Mrs Thatcher, who had once denounced the African National Congress, to which he belonged, as a "typical terrorist organisation".

There was not a word of criticism. He was generous and thoughtful, praising the role she had played in building pressure for change in South Africa.

Nelson Mandela had 14 years on the world stage before he retired from public life in 2004.

He had become one of the great figures of the 20th Century, a statesman who combined humanity and humour.

Even as he brought the curtain down on his years of public engagements, he did so with a quip: "Don't call me, I'll call you."

- Published8 June 2013

- Published26 October 2010

- Published17 July 2010