Scotland's watershed route mapped out for hikers

- Published

The watershed is the geographical feature that separates Scotland's river systems from east to west

It follows a line that's as old as the hills, and now Scotland's newest long-distance footpath has been marked out for hikers.

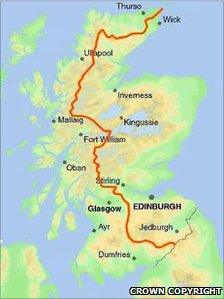

The 745-mile (1,200km) route follows the watershed, the line dividing river systems that flow west to the Atlantic from those that end up in the North Sea.

"Imagine you are a raindrop", Peter Wright, the new route's author, told me.

Frankly, that wasn't difficult.

On the day I met him in the Campsie Fells the cloud was low. The fog was high. And the drizzle was pretty constant.

"When you fall to ground you either have to go west, to the Atlantic Ocean. Or east, and end up in the North Sea."

'Big walking project'

Despite the weather, the scenery looked beautiful. Peter had brought me there to walk a short stretch of the watershed.

It's the geographical feature that separates Scotland's river systems. And the basis of what Peter hopes will be the country's latest long distance footpath.

"Back in about 2004", he told me, "I was looking for a big walking project.

"I wanted something that was going to be quite a challenge. Quite demanding. Something that hadn't been done before.

"One of the few subjects I was interested in at school was geography, so I reckoned Scotland must have a watershed.

"So I set about plotting the watershed on the map of Scotland, and it all took off from there.

"Once I'd plotted it, and worked out how long it was, I then started planning to walk it."

The route starts at Peel Fell, just across the border in Cumbria, and ends at Duncansby Head, overlooking the Pentland Firth.

It links Scotland's two National Parks - Loch Lomond and the Trossachs, and the Cairngorms.

It takes in 24 Corbetts (mountains between 2,500ft and 3,000ft); 44 Munros (mountains over 3,000ft); and eighty-nine protected sites or nature reserves.

Important feature

As we walked a tiny stretch of the watershed together we came across a mountain stream, fed by the rain running off the tops.

"I can say for absolute certain that the water in this burn is definitely going to flow into the river Kelvin, the Clyde, and eventually the Atlantic Ocean," Peter told me.

And the reason he could be so sure? Because we were just on the western side of the watershed.

But cross the ridge, and all the raindrops falling to the east of the watershed "will have a journey by bog, burn, and river into the North Sea."

I suspect that the term "watershed" is used most often these days by people thinking about what can be shown on television after the kids' bedtime.

But Peter - who was awarded an MBE for his work on the Duke of Edinburgh's Award scheme - reckons it is an important geographical feature.

"If we went to some other countries, notably north and south America, we would find that their watersheds are very well known, and indeed celebrated.

"But not the Scottish watershed. Because, as I discovered, nobody had actually ever defined it."

Scotland "from the air"

Having worked out the route, Peter told me he realised it was much more than a topographical curiosity.

It forms a strip of largely unspoiled wild land that skirts some of Scotland's biggest towns and cities, and goes through some of the most remote parts of the country.

By definition, it follows the peaks of Scotland's highest mountains.

Walking it would be like seeing Scotland from the air. But with your feet on the ground.

So what happens now?

In an interview for the BBC's Good Morning Scotland radio programme, Peter told me he hoped the route would be celebrated and appreciated.

And walked.

"There's an immense amount of opportunity for people to get out there, get their boots on, and have a good walk."

But isn't there a danger, I wondered, that by publicising the route Peter might turn it into another West Highland Way?

With route markers, B&Bs and camp sites, even companies that will ferry your luggage from one overnight stop to the next while you stroll along unencumbered?

"I'm not going to knock the West Highland Way", he responded.

"But I certainly hope that the watershed never suffers from any way-marking, or anything that's going to make it any easier.

"People who take on the whole watershed are going to have to be self-reliant. They're going to have to have good equipment.

"They're going to have to be fairly skilled at looking after themselves in remote country.

"And nothing can change that."

- Published10 March 2011

- Published3 March 2011