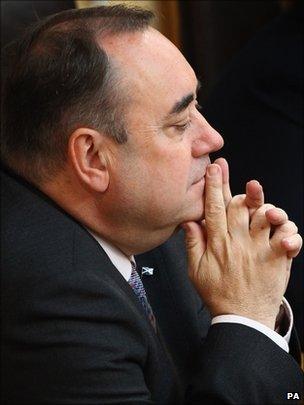

Salmond outlines Scottish vision

- Published

- comments

Glance through the list of bills in the Scottish government's new legislative programme, external and you will find little in the way of dog-whistle politics.

Yes, there are highly contentious measures - such as the reintroduction of minimum unit pricing for alcohol, the anti-sectarianism measures and the proposed single police and fire services.

These, along with other measures such as reform of social care and the protection of young people, will ensure that Holyrood's committees have a full workload.

But they are scarcely at the core of Nationalism. They are not why the party was founded three quarters of a century back. They do not reach to the deep in the SNP.

Look further, though, into Alex Salmond's address to parliament today , externaland you will find a revival and refinement of the broad political strategy which he pursued in the last session, while governing as a minority.

Look at the section on the economy. Look at the non-legislative provisions.

Therein, Mr Salmond promises to strengthen the economy to the full scope allowed by existing devolved powers - then links that to a demand for enhanced fiscal devolution.

In essence, he is again saying: consider our works, are we not sensible, are we not governmental, are we not moderate and controlled? Trust us with more power.

The message, of course, is expressed in rather blunter terms, now that he has a majority at Holyrood.

He asserts, although still in constrained language, that he now has a mandate from the people of Scotland for further powers to be transferred to Scotland.

He asserts that those people do not fear independence.

Look at the arguments to and fro on the issue of transferring control of corporation tax to Holyrood. The two sides are, to some extent, talking about different aspects of the debate.

SNP ministers and MPs at Westminster tend to talk about the principle of devolving corporation tax.

They assert it is Holyrood's right, they cite the proposal to devolve the tax to Northern Ireland. UK Ministers, including the Treasury, mostly talk about the consequences.

They suggest that the integrated tax system of the UK (or, more precisely in this instance, GB) would be undermined.

They argue that big cuts in corporation tax in Scotland would mean big cuts in the block grant.

Each side has issues to address.

The Scottish government does indeed have to address the cash consequences of slashing corporation tax. (They do so in outline by arguing that any cut would be phased in, potentially attracting investment by the very fact of signalling a future cut.)

The UK government needs to provide a more coherent explanation of why devolving corporation tax to Scotland would release a host of demons - when just such a plan is being advocated for Northern Ireland. (They do so in outline by arguing that the NI economy is more detached and faces direct cross-border competition from the low-tax Republic.)

At the core, though, are the consistent strategies of those advocating independence and those advancing the Union.

Those backing independence say: trust the incumbent devolved SNP administration to go further, to move to full power; the potential benefits.

Cuts anger

Those backing the Union talk up the anxieties and strains which they believe are intrinsic to such a radical change: the potential damage.

In addition, of course, there is a degree of impossibilism in Mr Salmond's approach.

He advances his case, fully aware that the Treasury is minded to say no. Thereby, he hopes to foster the impression that Scotland can not hope for fair treatment from the UK government.

At Holyrood today, opposition leaders were largely interested in the dog which didn't bark during Mr Salmond's address.

The absence of an early bill for a referendum on independence.

Why, they asked, did Mr Salmond not get on with it? Why not table the bill now? As so often in politics, they know the answer.

Because, right now, Mr Salmond is not confident he would win. Because he prefers to wait, to build the case. Because, right now, he wants to focus upon the economy and public services (remember that broad strategy.)

Because he hopes that public anger over impending cuts in public spending will turn ultimately upon the Treasury and the UK government, not his own team.

In contradistinction to that, those who advocate the UK will argue that Scotland alone would be too weak to counter global economic trends.

Big stakes, big politics. Sixteen bills in the legislative programme.

Some contentious, some worthy, some dull. The one that really matters? The Budget Bill, external.