Dr David Livingstone: A 200-year legacy

- Published

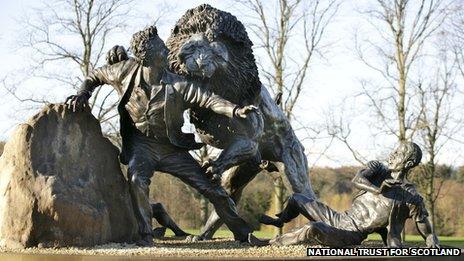

A statue in the grounds of the David Livingstone Centre helps portray the legend

A missionary, an explorer, a medic, an anti-slavery campaigner and Victorian celebrity whose death prompted displays of public mourning reminiscent of Princess Diana. It is 200 years since David Livingstone was born in Blantyre.

Tuesday's anniversary is being marked by a variety of events throughout Scotland and the wider world.

Livingstone's legacy continues to fascinate and prompt some very different opinions.

At the David Livingstone Centre in Blantyre, a tour group is being shown round the place where the world famous explorer and missionary was born. Many have visited the centre before - most on Sunday school trips.

Grit and determination

A narrow, spiral staircase brings the group to the single room where David Livingstone lived with his parents and siblings. It is small, with two beds recessed into the wall and two more underneath them.

It would have been cramped, but by the standards of the time, the conditions in the room and at the local cotton factory, where the family worked, were decent.

"It was very interesting to hear how he grew, how he developed from very little to become a doctor," commented one man in the group, "a missionary involved in the anti-slavery situation at the time."

Between working in the mill and going to Africa was a story of grit and determination. After working all day, the young David Livingstone did school work in the evenings. He later studied medicine and theology in Glasgow.

"Livingstone had a really strong Christian faith," said Karen Carruthers, the property manager at the David Livingstone Centre. "And he really struggled as a young man to find a way of reconciling that faith with his interest in the world about him and developments in science.

"He heard about a chap who was a medical missionary in China. Livingstone saw this was a way that he could combine both his interest in science and the world around him with his Christian faith.

"He is a great example of what people can achieve from even the most humble of backgrounds.

"I think he's also remembered rightly for his campaigns against the East African slave trade. He's also remembered as a great humanitarian."

Prolific writer

During his lifetime, Livingstone became an international celebrity of the Victorian age, who counted Charles Dickens among his fans. He was awarded the freedom of various cities and a number of honorary degrees.

At the time of his explorations he wrote prolifically and in a style that was very accessible.

"Newspapers picked up on the stories," explained Dr Joanna Lewis of the London School of Economics

"Of course he found things like the Victoria Falls. He was mauled by a lion. So he was always doing lots of derring-do.

"Then at the time of his death, He died in pain, miserable and alone as people saw it in central Africa, believing that his great quest for the Nile had failed, believing that his campaign against slavery had died.

"The Victorians were profoundly upset. How come this man who'd sacrificed so much, how come he had such a horrible death? It was a bit like the death of Princess Diana, people were weeping in the streets."

But how should we view him now? He wrote thousands of letters to members of his family, to politicians, to other missionaries, to scientists. He also kept journals and diaries.

In these wide and varied pieces, he was often writing off the cuff, he expressed many different views and sometimes changed them. They show different David Livingstones.

Complex story

"Some people have depicted him as an imperialist, I don't think he was," said John MacKenzie, emeritus professor at Lancaster University, who specialises in the history of empire and imperialism.

"I don't think there's any doubt that a lot of the information he gathered fed into imperialism and was useful because knowledge does always lead to power."

He said it was a complex story. "What we can say is that later in the century after his death in 1873 lots of other people pursued imperial policies using the name of Livingstone as a kind of patron saint.

"So once he was gone and conveniently off the scene he then became a kind of ancestor figure, a saintly figure who could be used by others for their own ends in order to promote the development of colonies."

Part of David Livingstone's modern legacy is the strong links which exist between Scotland and countries like Malawi and others in elsewhere in Africa.

Many people from there visit the David Livingstone Centre.

"It's clear that for a lot of our African visitors," said Ms Carruthers, "it's almost like coming home in a way because they know so much about Livingstone."

As for his anti-slavery campaigning "unquestionably he gets full marks from me for that," said Dr John Lwanda, who is originally from Malawi but has lived in Scotland for more than 40 years.

The David Livingstone Centre in Blantyre houses some of Dr Livingstone's notes and diaries

"David Livingstone's influence in Malawi has been good and bad," he added.

"Malawians overwhelmingly like David Livingstone. He brought Christianity; he introduced Malawi to the outside world. One of the bad things that he did, when he opened up that part of Africa it led to the scramble for Africa and in the case of Malawi we were left with a small sliver of land, the rest was taken away from us."

In April, in the Zambian town which bears his name, scholars from Africa and around the world will be gathering to talk about Livingstone and assess his legacy. The conference is entitled Imperial Obsessions - David Livingstone, Africa and world history: a life and legacy reconsidered.

The idea is to exchange and discuss both new and old ideas.

"He used to be very much a marmite subject," said Dr Lewis, who is one of the conference organisers. She is expecting some lively debate.

"Either you loved him or loathed him. You loved him because he was a great explorer, a humanitarian and he was a great Scotsman or you loathed him because you blamed him and other missionaries and explorers for bringing colonial rule to Africa.

"So he's been quite a divisive figure. But we have I think a more balanced view now, as we acknowledge that to understand that encounter with Africa in the 19th Century that was so significant for that continent, that figures like David Livingstone have to be looked at, there's no getting away from them."

- Published18 March 2013

- Published23 November 2012

- Published20 June 2012