Professor Peter Higgs: in his own words

- Published

BBC Scotland's Kenneth Macdonald talks to Professor Peter Higgs, the Edinburgh University physicist who proposed the existence of a new particle which would become known as the Higgs Boson.

It was an idea that changed the Universe - or at least how we look at it.

Here, in his own words, Higgs explains how "incompetence" in the lab led to him pursuing theoretical physics, how it should be the Goldstone boson and why he does not like the "God particle" label.

Early years

"What kind of pupil was I? Well, I was a swot, but I was allowed to be without any ill effects by my contemporaries because I was excused from games, due to my asthma. So being a swot was something to compensate for not being to play football.

Higgs said he was not hugely interested in the physics he was taught at school

I was already, I think, at the age of 18, showing signs of being incompetent in the lab.

My recollection of the higher school certificate, which involved a practical exam in physics, was being confronted with an experiment involving a sort of barometer arrangement, wondering why I couldn't make it work.

That sort of set the scene for me and when I chose to go to university, which was Kings College London, I continued to show all sorts of symptoms of incompetence in the lab while I was a student there. So very early on, I was heading towards the theoretical end of physics as the only kind of thing I was competent in."

Working in Edinburgh

"I liked Edinburgh as a university in a way that I'd never enjoyed King's College London. I realised after I came to Edinburgh that perhaps it was a mistake to have gone to a college which was bang in the centre of a vast city. It had a bad effect on the social life of the students because a lot of them were commuting from outer London.

Edinburgh was much better as a place to live. If I'd been a student there I would have had far more friends than I ever had in London.

When I moved back to Edinburgh I'd been doing work in quantum gravity but I couldn't see any useful way of extending it at the time, I was sort of at a dead end. I didn't know what I was going to do so first of all, in Edinburgh, in the summer of 1960, I was roped into the organisation of the first Scottish university summer school in physics at Newbattle Abbey College, before taking up the lectureship in October.

In my first year of teaching in Edinburgh I began to do more reading and on things which I hadn't thought about in the last few years. By the end of my first year, I had read papers by Yoichiro Nambu and that was when I was converted to the ideas that Nambu had formulated. I thought that this was a good way of formulating field theories for elementary particles and that I would work in that area myself."

His discovery

"It shouldn't be a Higgs field. If it's anybody's it should be Goldstone field, I think. When Nambu wrote his short paper in 1960, Jeffrey Goldstone of Cambridge University, who was visiting Cern, heard about it. He then wrote a paper which was conceptually similar to what Nambu had done, but a simpler model.

The hunt for the Higgs has been compared by some to the Apollo programme that reached the Moon

The one thing which was missing at that time, in 1960-61, was that in formulating the models intended for the strong interactions of elementary particles, Nambu and Goldstone ignored electromagnetism. For some reason they didn't include it in the basic dynamics. Like everyone else, they thought electromagnetism was a small effect. We're after a theory of the strong particle interactions. So they left out electromagnetism and what did they get instead? They got what were called Goldstone Bosons, a set of particles with no spin and no mass. And that spoilt the theory.

There was a period of about two years in which people argued about it in the literature. Then, in 1964, my realisation of what the answer was simply came over a weekend, after I'd read a paper which seemed to shut the door on any exceptions to this theorem. I got very upset over that paper."

'The God particle'

"That name was a kind of joke, and not a very good one. An author, Leon Lederman, wanted to call it 'that goddamn particle' because it was clear it was going to be a tough job finding it experimentally. His editor wouldn't have that, and he said 'okay, call it the God particle', and the editor accepted it. I don't think he should've have done, because it's so misleading."

First visit

"My first visit to the Large Hadron Collider was in April 2008, before it started up, and Cern had some open days. They were slightly shocked by the end of it because I think they got something like 50,000 visitors. The group from Edinburgh were slightly privileged and went through on a conducted tour just before the mob arrived. And it was extremely impressive.

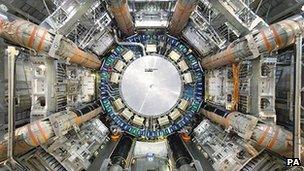

Higgs was stunned by the scale of the Atlas detector during his first visit

I knew about the scale of the machine, the circumference of the tunnel and so on, so that wasn't surprising. But the size of the detectors was the really amazing thing. I mean, the Atlas detector, which is the one that the Edinburgh and Glasgow groups are involved in, is said to be bigger than Salisbury Cathedral. It's really amazing.

I was a bit unhappy about the way it was being sold. Not because I didn't think they should go after the Higgs Boson, of course, but I thought they should have educated people more about the breadth of the programme of the machine, and not concentrated on this so much. It seemed to me they were taking a risk that when they found the thing, then a lot of people would say 'oh well, that's it, isn't it? Why do we still want this machine?'"

The announcement at Cern

"By the evening of July 3rd, it was clear there were people camping outside the lecture theatre in the hope of getting a seat the next morning. Apparently during the night there was a fire alarm, the fire brigade were called and the people camping refused to move. When the time came on the Wednesday morning, I had to have a sort of bodyguard to get me through the crowd outside the lecture theatre.

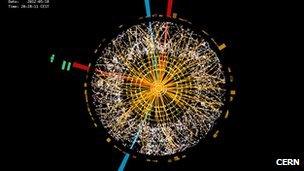

Scientists involved in the Cern describe the moment they were told a new particle consistent with the Higgs boson had been discovered

I think I got the worst of it because of the way the publicity is concentrated on my name, but there were three other people there out of the six of us who did the work in '64.

I'd never been in a scientific meeting like that before, because people got up and cheered and it was a completely new experience.

I didn't accept it was me that they were cheering. I regarded it as cheers for the home team, as at a football match, and the home team were the two experiments, Atlas and CMS, with 1,500 members each. That's what it was really about. Maybe they were cheering me too but that was a minor issue."

BBC Scotland Investigates: Peter Higgs: Particle Man will be broadcast on BBC1 Scotland at 22:35 on Wednesday 17 April, and for a week later on the BBC iPlayer.

- Published10 April 2013

- Published17 April 2013

- Published21 June 2012