What are botanic gardens for?

- Published

The Cruickshank Botanic Garden at the University of Aberdeen

Their advocates say they are a store of knowledge, which could help tackle many global problems and offer a chance to live in a timeframe not bound by instant messaging, but across the world many botanical gardens are having to face challenges, often related to funding.

The way ahead for one of them, St Andrews Botanic Garden, remains uncertain in the face of an upcoming cut in its funding.

The 16th century roots of botanic gardens lie in medicine but their more modern roles encompass research, education and conservation. So what are botanical gardens actually for?

Some welcome spring sunshine makes a chequer-board pattern through the trees at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh.

Beneath them, compost is being sieved into a wheelbarrow prior to planting and all around there are signs of activity and long waited for growth.

"Here we are only a mile from the centre of Edinburgh and yet this institution, because of its three and a half centuries of history, is cultivating one in 14 of the plants on this planet," says Alan Bennell, head of interpretation at the garden.

Experts from the garden are active in more than 40 countries across the world.

Edinburgh's botanic gardens cultivates one in 14 of all the plants on the planet

Botanic gardens have their roots on the continent and were intimately connected with the study of medicine.

Mr Bennell continues: "If I take us right back to the mid-1500s a number of early botanic gardens were founded on the continent and they were physic gardens.

"The very first is recognised in Padua, (in Italy.) It's still there."

Two Edinburgh doctors were doing their version of the European tour and when they saw this work going on they became determined to improve the practice of medicine at home.

Mr Bennell says they were inspired by what they had seen on the continent: "Namely, if you're treating people with potions derived from plants you need to consistently know what plant it's coming from, how do I recognise it, what are its close relatives."

Drawing of a tree transplanting machine used when the Garden moved from Leith Walk to Inverleith

The Edinburgh garden has been on different sites in the city. Its varied scientific and research work is supported by public money and funding also comes from other sources including grants.

In many ways the history of the great botanical gardens mirrored the wider history of the society around them.

In Edinburgh's case it continued to develop, reflecting the fact that Scots entrepreneurs, pioneers, medics and missionaries were out in the world collecting and sending back new plant material.

There is a whole network of botanical gardens across the world and a number here in Scotland, including in St Andrews, Dundee and Aberdeen.

Botanic gardens are defined as being different from parks in having documented collections of living plants and a purpose which includes an element of scientific research, conservation and/or education. But their purposes can be very varied.

"Some will have a particular focus on education and public outreach," explains Suzanne Sharrock, director of global programmes at Botanic Gardens Conservation International, an organisation which links gardens around the world.

"Others are much more focused on conservation issues, they have seed banks and gene banks and they're conserving threatened species.

"There's an increasing focus on conservation of native diversity and that's particularly the case in some of the newer gardens that are being established in developing countries.

"Some gardens are involved in monitoring plant collections for climate change, things like control of invasive species, perhaps development of new plants for commerce, that's still an activity in some gardens."

It is a day of sunshine and showers in Glasgow's Botanic Gardens, in the west end of the city, and as a watery version of that sunshine appears, both gardeners and the public begin to emerge from the glasshouses.

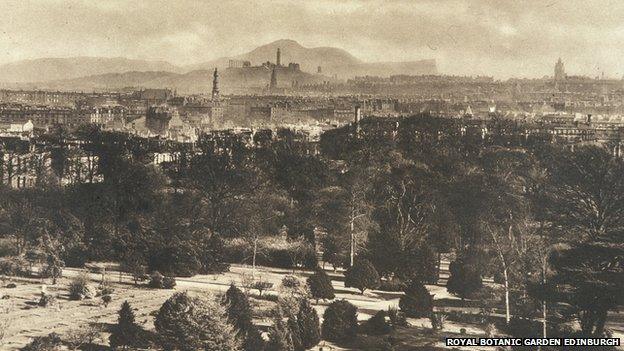

Looking out over the city from Inverleith gardens in Edinburgh

The gardens were set up in the 19th century by a distinguished Glasgow botanist, with the support of, among others, the university. They are now run by the council. But why do people come here?

"I've got two young children," says one woman, pushing a buggy along a path between the flower beds, "so it's an ideal spot to let them run around."

A couple coming out of the glasshouses say they come to look at the plants, meanwhile, a woman sitting on a bench warming her face tells me she is an almost daily visitor.

"They call this the old folk's row," she laughs pointing to the seat, "because all the sun comes to this bit, so everybody sits here in the good weather and they get lovely tans."

Whatever draws people now, many botanic gardens began being very closely associated with universities.

Yet the world has been changing around them. Across Europe, the teaching of botany as a distinct subject has been in decline in many universities and amid tight budgets some gardens have been forced to prove they still matter.

"They have to adapt," says Ms Sharrock.

"The important thing is they have to show their relevance in today's society.

"It's a slight contradiction in that so many of the problems or the issues that society is facing are related back to an understanding of plant science. Things like food security, climate change, dealing with invasive species."

The Cruikshank has the remits of research, learning and engagement

In Aberdeen, the university has the 11-acre Cruickshank Botanic Garden right on campus.

Various university departments use it and its curator, Mark Paterson views part of his role as being to raise its profile further, both in and outside the university.

"It has, as far as I'm concerned three major remits, that of research, that of learning and public engagement.

He wants the public to see more of what goes on behind the scenes.

Mr Paterson says: "I'm promoting more and more of that in the garden for people to see, the vital academic and research work of plant science - let's show some of it off front-of-house as well."

He explains his love of gardens in this way: "I do not live daily in the timeframe of our modern communications of instant messaging.

"I'm thinking of seasons, I'm thinking of decades, I'm thinking of centuries, depending on the plants that one is trying to grow."

Further south, and St Andrews Botanic Garden has been in existence since 1889, but its future is now uncertain.

The university says it is no longer used for research and Fife council which has been leasing the site says it will need to half its funding over the next two years.

"When you think about it, there can't be many towns the size of St Andrews that has a botanic gardens," local councillor Brian Thomson told Radio Scotland.

He explained that the council is looking to make savings across a range of services but that he hoped it could still be a partner or assist in some way toward setting up a trust which could access "a lot of external funding" and come up with some ideas to "rejuvenate the garden".

Back in the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh and several visitors are standing by a small stream as it hurries its way across stones and through rich planting. They seem to be just enjoying the sights and sounds.

Throughout the years, plants have been brought here from all over the world and now, in the form of its outreach work, knowledge flows the other way.

"Think of how many things we use plants for," concludes Alan Bennell.

"You fed on them this morning; you're probably wearing cloth made of them, the pharmaceutical industry, the forestry industry, the fabric industry.

"The medical industry still needs plant knowledge more than ever and yet out there in our planet there is this other great threat.

"Mankind is steadily eroding the very diversity base that is the future basis for future generations to have all of this.

"It's all very well wittering about conservation, if you don't know what it is you're trying to conserve, you don't have that basis understanding of what's out there."