First Minister's Questions: Politicians support shipyard workers

- Published

The exchanges were robust. Very robust. But, instead of considering independence in the abstract, this session at Holyrood was dealing directly with the future for hundreds of jobs on the Clyde.

This was particularly pointed for the main participants on this occasion - Nicola Sturgeon and Johann Lamont. Govan shipyard lies in Ms Lamont's constituency and abuts Ms Sturgeon's fiefdom.

That led them each to acknowledge the sincerity of the other. Johann Lamont said she did not doubt the determination of the deputy First Minister to fight for the interests of the workforce, as she saw them.

Nicola Sturgeon - deputising for the First Minister, who is in China - said she accepted that Ms Lamont's concerns about the possible impact of independence were genuinely held - and she respected that. However, each also believed their rival to be sincerely wrong. Hence the robustness.

The essence of Johann Lamont's argument was that independence could jeopardise the placing of orders for new Type 26 warships on the Clyde.

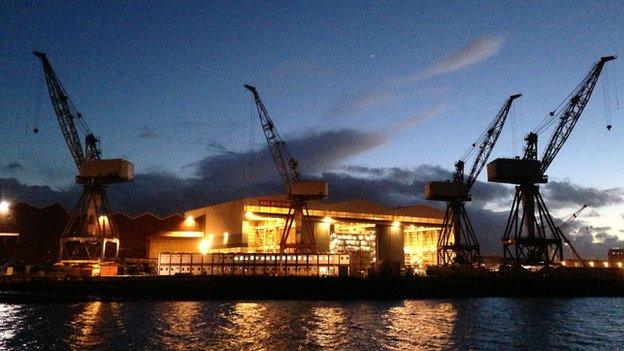

Shipyard jobs are to go at the Govan site

She said the Ministry of Defence did not traditionally place warship orders outside the UK. Why, she asked, would they break that custom for an independent Scotland which, by then, would be an independent country?

Nicola Sturgeon listed examples of the MoD offering to collaborate on the T26 warship with Australia and other countries on grounds of cost. Was it simply Scotland which would be excluded?

She argued further that the Clyde was not just the best place to build the T26. It was now the only place.

Then robustness kicked in still more bluntly. Ms Sturgeon accused the Scottish Secretary Alistair Carmichael of letting down Scotland. (He had warned that the orders might not go to Glasgow in the event of independence.)

And, directly, she accused Ms Lamont of seeking to "bully and blackmail" the workforce on the Clyde. Joint procurement between Scotland and the remainder of the UK, with orders placed on the Clyde, would make sense.

Joint deal

Ms Lamont retorted that she was in favour of joint procurement. It was called the United Kingdom. She earnestly hoped that situation would continue to prevail.

Both other party leaders pitched in on shipyard orders. And, to her credit, the Presiding Officer allowed the exchanges to run long, rightly judging that the chamber and the people of Scotland wanted to hear the full debate.

For the Conservatives, Ruth Davidson offered a notably measured response - and, on the day, a rather effective one. Quietly and without rancour, she urged Ms Sturgeon to offer every possible support to the Clyde yards to build the global expertise which, she said, was now required for specialist warship yards.

For the Liberal Democrats, Willie Rennie recalled that Ms Sturgeon had previously suggested that a fisheries protection vessel order should be reclassified as a "grey ship" (that is, military) so that the work could be diverted to Scottish yards. Did that not clash with her demand now that rUK post independence should give work to Scotland?

Ms Sturgeon said that Mr Rennie was misunderstanding the nature of the relevant EU regulations. They allowed a member state to protect its security with regard to the placing of orders. That did not mean, she argued, that orders must be placed within the boundaries of the state. It did not preclude, she argued, a joint deal with an independent Scotland to place Type 26 orders with BAE - and for those orders to be filled on the Clyde.

- Published7 November 2013

- Published7 November 2013

- Published6 November 2013

- Published5 November 2013