Scottish independence: Who pays price of Scots currency?

- Published

I'm writing from London, where retail staff are looking even more askance at my Scottish banknotes. It's filtering back to the metropolis that something is up on the future of the British pound.

Watching the debate from a distance on the Scottish government's currency options after a referendum 'yes', it's striking how scratchy it's become. Both sides know this matters.

I've taken some travelling time to look again at the assessment of currency options published by the Treasury last week, external.

To be more accurate, it's an assessment of one currency option - a formal currency alliance, with shared control of sterling.

And while every one of these Whitehall papers on the independence debate has been steered towards the case for retaining the UK union, this one is a lot more forthright. Brutally so.

The highly unusual, personalised back-up of a letter from the top Treasury mandarin, Sir Nicholas MacPherson, external, emphasised as much.

As I noted last week, this is the first time we've heard Whitehall articulate the voice of the rest of the UK (rUK). It hadn't intended to, but it did.

You may agree with the Scottish government that it's bluff, and there will be goodwill and co-operation once negotiations get under way.

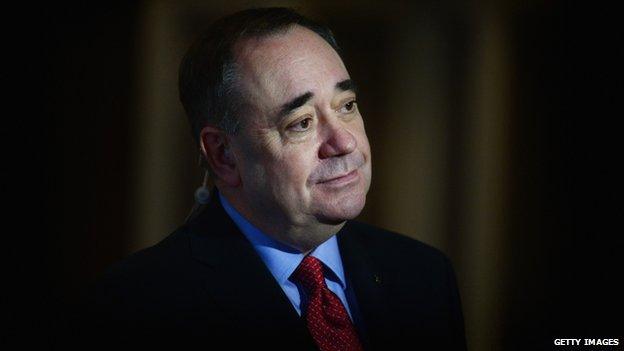

Having digested it, and Alex Salmond's response this morning, my reckoning, for what it's worth: that would be a brave thing to do.

It's your judgement as to whether it's bullying or ill-judged in tone. But I got the sense these Treasury officials meant what they wrote.

Embedded in Treasury thinking is an instinct to fight its corner ferociously, even with departments in its own government.

And all the more firmly embedded after the banking and Eurozone crisis, it protects its own independence.

But just suppose they do a U-turn on negotiating a deal after a 'Yes' vote, it's worth noting two sentences in particular from Scotland Analysis: Assessment of a sterling currency union.

"Regular monitoring of an independent Scottish state's fiscal position by the continuing UK would be required in a currency union, including some mechanism for intervention and correction if fiscal risks to the stability of the currency union were to arise.

"These constraints would limit a future Scottish government's ability to use fiscal policy to support the economy."

In other words, Treasury officials from London would treat the Scottish Treasury as accountable to them, requiring regular updates, with London expecting to have the power to overturn spending and taxation decisions.

That's more power than it currently has over Holyrood, and without any hint in the assessment that such an intrusion into an independent nation's finances would be reciprocated.

Humility

There are two elements of the Treasury analysis that are striking for their absence. One - and this is true of all these Whitehall assessments - is an absence of humility.

When it points out that Scotland would inherit debt of at least 84% of national output, and a deficit that could be running at more than 5% (that is, needless to say, a disputed figure), it's impossible to find even a footnote that explains this might have something to do with the Treasury's handling of the public finances.

When it talks about the sharing of risk between London and Edinburgh if banks collapse, it doesn't have to explain to its readers what that means. It's not theoretical. That's what happened recently, on the Treasury's watch, due to a failure of oversight.

It's not long ago that the Treasury could argue that Scots would be idiotic to part themselves from such a Rolls-Royce operation as the UK government's handling of the economy and the taxpayer pound.

They're not claiming that now.

Exchange costs

The other factor that's missing is a clear reckoning on the downsides of the rUK refusing to sign a deal on sharing the currency.

The argument looks like a balanced one. Some might say it's finely balanced. The Treasury clearly would not agree.

But by not acknowledging the downside of a refusal to agree a currency union, it's left the field open to economists in St Andrew's House to fill in some gaps.

They've come up with a figure of £500m costs to rUK business from introducing currency exchange transaction charges to exporters' bills.

"My submission," said Alex Salmond, "is that this charge - let us call it the George tax - would be impossible to sell to English business."

Economic exercise

Two observations on this.

It is based on "experimental" statistics about trade between Scotland and the rUK. There are some bold assumptions behind it.

But more significant, its inclusion in Alex Salmond's speech in Aberdeen, responding to George Osborne, appears to hint quite strongly at the direction of the first minister's thinking for a Plan B.

He's got his economists to figure out the implications of only one scenario: Scotland setting up its own currency.

Their figure of around £500m is drawn from research into the impact of removing exchange costs from the Eurozone, not including oil and gas exports.

When I say "around", they're saying it lies between £370m to £630m.

And it may be worth noting that the costs saved from removing a currency exchange barrier (the creation of the Eurozone) may not be the same as those added by creating one (a new Scottish currency).

Anyway, if business in the rUK could expect to face £500m exchange transaction costs, then it follows that Scotland, with lower sales of goods and services into the rUK, could - very roughly - expect a business cost of £400m. A smaller figure, but proportionately a lot more.

And that's at the lower end of potential estimates.

The Scottish government conservatively assumed that currency exchange inhibits 0.1% of Gross Domestic Product in the rUK. It could be double that.

But its economists' background paper says that for a small country, Eurozone research suggests the impact could go as high as 1%.

That is: the full cost to Scottish businesses of introducing a separate currency could be, proportionately, much greater than that estimated for the rUK.

It's not obvious why the first minister would wish to draw attention to such a big potential blow to trade.

While it might hurt rUK businesses selling into an independent Scotland, it looks like it would hurt Scottish businesses far more.

And it's on the Scottish side of the border that the votes are, where voters may not much like what George Osborne had to say, but they may also doubt that he was bluffing.

If, as Alex Salmond suggests, George Osborne hasn't bothered to factor in the cost to rUK business of trading in a different currency, it may be because he's taking his own gamble - that Scotland would choose to use the pound as its currency, but without a formal currency union.

That way, transaction costs would barely change; it would limit the impact for sterling of a change in the oil price; the rUK would not have to make compromises with an independent Scotland on sharing monetary controls and the insurance of a banking union; and the worst concern for the rUK Treasury would be the volatility its assessment foresees in the Scottish economy, reducing demand for English, Welsh and Northern Irish sales.

Asset or not?

I offer one other element worth noting in the Treasury's assessment, relating to much of the debate around whether Scotland retains a right to share control of the pound.

It's been described, from the nationalist side, as an asset. And if an independent Scotland doesn't get a share of UK assets, it is argued it should not be expected to take on a share of the liabilities - primarily, Britain's government debt.

The Treasury's response to this is that the pound is not an asset, but a system underpinned by a legal, institutional and administrative framework, which allows it to function as a medium of exchange, store of value and unit of account.

Assets, it is argued, include cash, currency and gold reserves, and these "may be subject to negotiation" in the event of a 'yes' vote.

But "the assets held as backing for a currency are not the same as, or equivalent to, the currency itself".

I don't expect that's going to end the debate. But it might help inform it.