World War One: The woman who took on the slum landlords

- Published

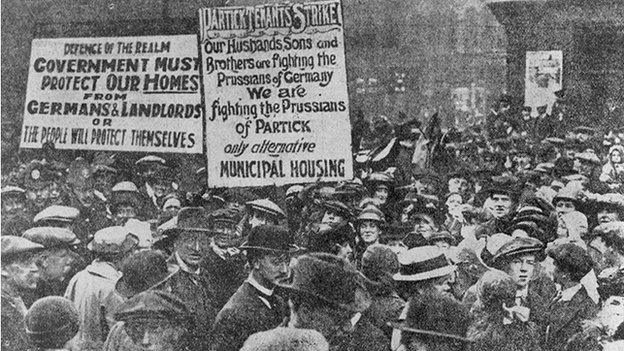

Thousands protested against the injustice of rent rises while the country was at war

Private landlords seeking to cash in on the demand for housing during World War One did not reckon on a working class housewife rousing thousands of women to join a protest that led to restrictions on their power.

The outbreak of World War One saw many men leaving home to join the fight on the Western Front, but in Glasgow it also brought thousands of workers to the city to take up jobs in the shipyards and munitions factories.

The city's housing was already overcrowded and in a poor condition but, in the days before widespread council housing, private landlords saw this extra demand as an opportunity to raise rents for the thousands of tenants.

The rent rises were steep and aroused fury in working class districts such as Govan, the home of Mary Barbour, the driving force behind the resistance.

Dr Catriona Burness, who has been researching the life of Mrs Barbour, said: "In Glasgow you have got an overcrowded population living hugger-mugger in tenement flats, often slum flats.

"When war came, men went to the front but their families were left behind.

Mary Barbour led the protests about the rent rises

"At the same time there were more workers coming into the city, essential workers for the shipyards and in munitions factories."

Dr Burness adds: "The landlords saw the opportunity to put rents up and there was an immediate reaction against having rent increases at a point when the country was in crisis.

"People were being moved into extraordinary situations and, at the same time, private landlords were taking the opportunity to increase rents."

Mrs Barbour, by this time a 40-year-old housewife with two children, had been born into a carpet-weaving family in Kilbarchan, Renfrewshire.

When she was 21 she married an engineer who worked at the Fairfield shipyard and settled in Govan, becoming an active member of the Kinning Park Co-operative Guild.

She also became a member of the Independent Labour Party and the Socialist Sunday School, but it was the Glasgow rent strike that brought her to prominence.

Mrs Barbour was involved in every aspect of activities, from organising committees to the physical prevention of evictions.

The women who refused to pay the rent rises organised networks and systems of resistance which involved one woman in each tenement keeping watch for the bailiff's officer coming to evict a tenant for arrears.

Rent strike

When he appeared the lookout would ring a bell and the other women would rush to hurl flour bombs or other missiles at the bailiff to stop him carrying out his work.

By November 1915 as many as 20,000 tenants were on rent strike and the protest was spreading beyond Glasgow.

A decision by a Partick factor to prosecute 18 tenants for non-payment of a rent increase brought the crisis to a head.

On 17 November thousands of women, sometimes dubbed Mrs Barbour's Army, marched to the sheriff courts along with thousands of men from the shipyard and engineering workers.

The arrest of tenants who refused to pay the increase led to a huge protest

Maria Fyfe, former Labour MP for Glasgow Maryhill, said: "If you had been standing outside the sheriff court on that day you would have seen an enormous crowd of people, 20,000 or more.

"Women had come from all over Glasgow, men had come out of the shipyards and the munitions works, and they were gathered all the way back to the City Chambers in George Square, filling the streets.

"They were singing songs, waving placards, and they had speakers such as John Maclean, Willie Gallacher and James Maxton, heroes of Glasgow's Red Clydeside days. It must have been very exciting."

Inside the court they were feeling alarmed and a call was made to David Lloyd George, who was munitions minister in the coalition government at that time.

Ms Fyfe says: "Lloyd George said to them 'release the tenants and I will get something done'.

"He said 'I promise you, action will be taken'.

"So a huge cheer went up outside in the street. Apparently they were partying for hours afterwards."

Lloyd George was as good as his word. The Rent Restriction Act was passed only a month later to bring rents back to pre-war levels throughout Britain and to hold them at that level for six months after the war was finished.

Ms Fyfe says: "What Mary Barbour achieved that day was something that benefited tenants across the whole of the country and I think she was real heroine."

After the war Mary Barbour was elected to Glasgow Town Council as its first woman Labour Councillor.

She later became Glasgow Corporation's first woman Baillie.

She died in 1958 at the age of 83.