Life and death on the A9

- Published

The A9 is the road Scots love to hate, holding a reputation as both the gateway to the stunning scenery of the Highlands and as Scotland's most notorious killer road.

It is Scotland's longest road, stretching 273 miles (439km) down the spine of the country from Scrabster harbour in the far north to the Forth Valley in the south.

The A9 has been patrol officer Pc Fraser Cameron's beat for the past five years and he says it is "absolutely fantastic" to have an office with such amazing views.

"A lot of people travelling the road on a daily basis become immune to what's in front of them," he says.

"They miss the scenery, just wanting to get from A to B."

The scenery on the A9 can distract motorists

Truck driver Alex Stewart tells the BBC Scotland programme Life and death on the A9: "When there are tourists here in summer time they are mesmerised by the views. You've really got to watch out for them."

Tourists unfamiliar with Scotland's roads are just one reason why the A9 is considered one of Scotland's most dangerous road.

Its reputation is also linked to a confusing road layout, long stretches of single carriageway and motorists stuck behind high volumes of heavy goods vehicles, which are restricted to 40mph, leading to driver frustration and dangerous manoeuvres.

Pc Cameron rejects the killer road tag, saying: "I wouldn't class it as that. It is the people who travel it that cause the problems one way or another."

He says driver impatience is a big problem, as many people squeeze past the car in front, or overtake where they should not, just to save a few seconds.

Alex Stewart, who has driven the A9 for 39 years, agrees, saying: "In my eyes a lot of this is down to frustration and people being in a serous hurry and that's when it goes badly wrong for a lot of people."

A road layout that confuses drivers has been blamed for some of the accidents on the A9

Plans are under way to upgrade an 80-mile (128 km) section from Perth to Inverness to full dual carriageway at a cost of £3bn.

Transport Minister Keith Brown said the upgrade was the biggest transport project in Scotland's history and would not be completed until 2025.

However, some sections will be dualled well before then, with the Kincraig-Dalraddy stretch due in 2017 and the Luncarty- Birnam stretch in 2019.

Mr Stewart says: "The A9 is at the stage now where it has got to be dual carriageway.

"This road is really busy. We have paid the road fund licence we are surely entitled to a safe and decent road.

"It is none of the two just now. It is bumpy, it's lumpy. It's done."

Jo Blewett, Transport Scotland's project manager for the A9 upgrade, says: "I can understand the public wanting us to go faster.

"There is a huge desire for this road to built up to a suitable modern and safe standard."

But she says there are huge challenges and it is a very complex project.

There have been calls for improvements to the A9 for years, but changes to the road have been constant over the decades and much of the road only dates back to a major revamp in the 1970s and 1980s.

A much-needed upgrade which began about 40 years ago involved diverting the River Tay just north of Dunkeld and bypassing 18 towns and villages.

The Kessock Bridge was opened in 1982

The Kessock Bridge, which spans the Beauly Firth from Inverness to the Black Isle, was one of the 12 bridges built in the original upgrade.

Construction of the bridge began in 1976 and it opened in 1982. Along with the Cromarty Bridge it shortened the distance north by 14 miles (22 km), cutting out Beauly, Muir of Ord, Conon Bridge and Dingwall.

Together with the Dornoch bridge, which opened in 1991, about 90 minutes was cut off the old A9 journey time.

Three decades on and the Kessock Bridge is undergoing a full resurfacing job, with the road surface being completely removed and re-laid.

The improvements to the A9 in the late 1970s opened up the Highlands for tourists from the UK and beyond.

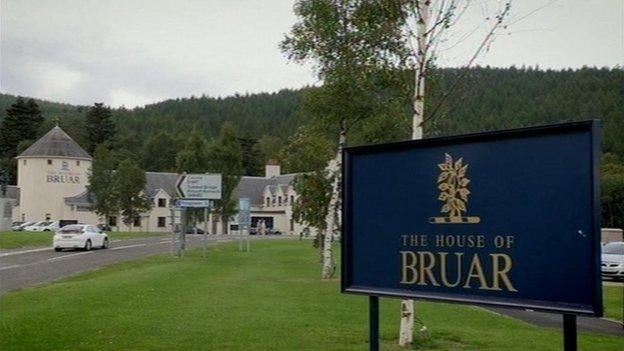

The House of Bruar relies on the A9 for its customers

One business that has benefited from the increase of tourist traffic is the House of Bruar, the clothes, food and homewares retailer founded 20 years ago by Mark and Linda Birkbeck.

It occupies an 11-acre site just off the A9 by Blair Atholl in rural Perthshire, and among its other attractions is the biggest cashmere clothing department in Britain.

An estimated 1.2 million visitors stop by the House of Bruar every year, many staying to eat in the extensive food halls.

Managing director Patrick Birkbeck says: "Without the A9 we would not have any customers."

The truckers' breakfast at the Motorgrill at Balinluig

Fifteen miles (24 km) down the road at Ballinluig is the Motorgrill, set up by owner Clive Bridges more than 30 years ago.

He says people do not visit his venue to linger.

"Most people come in, get their food, get their fuel, go to the toilet and go," Clive says.

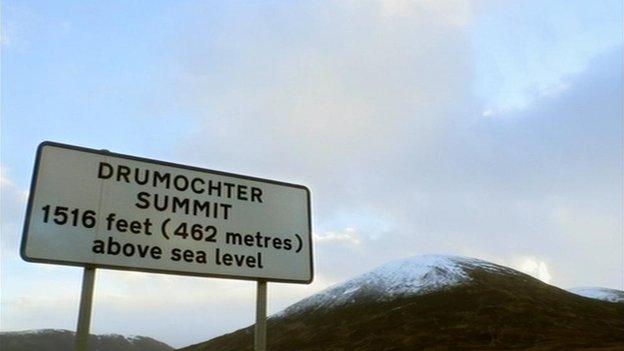

Drumochter Summit is the highest point on the A9

The A9 travels through hundreds of miles of varied and challenging terrain.

Drumochter Summit - 1,516ft (462m) above sea level - is the highest point on the A9 and one of the highest roads in the country.

For the police and snow plough teams it is a constant battle to keep the road open.

Alex Stewart says very few people prepare for the possibility of getting stuck in a "tin box" in -10C.

Snow plough driver Billy says: "You can guarantee you will see four or five near-misses every single run. They will just about get in in time and no more.

"But we'll never be able to educate them and tell them to wait until there is a space to overtake."

The snow gates are closed to prevent cars getting stuck in the worst of the winter weather

The A9 also has another hazard that is less obvious than heavy traffic or bad weather.

Last year there were about 200 deer strikes on the road.

Pc Cameron ended up in intensive care himself three years ago when a deer came out in to his path while the officer was on his motorcycle.

For forestry ranger Malcolm keeping deer numbers down is a year-round job.

He says: "They are big solid animals, and if you hit a deer on the road when you are doing 60 mph or 70 mph there is a good chance of your car getting written off.

"There is a good chance of people getting injured or worse. There is a lot of crashing happening with people either hitting the deer or swerving to avoid the deer and hitting other cars."

Malcolm has seen a lot of the road over the years and does not think it is very bad.

He says: "You see some crazy driving right enough but I don't know if it is any worse than any other road.

"To be honest I quite like the road. It has got some bonny spots on it."

Life and death on the A9 is on BBC Scotland at 21:00 on Thursday 6 March.