Funding the future: New wave of NHS 'big build' projects

- Published

The Aberdeen Community Health and Care Village brings together a range of services on one site

A health and care centre in Aberdeen is the first NHS project to be financed under a new system for funding major public building projects. But how is the new system, overseen by the Scottish Futures Trust, different to the controversial Private Finance Initiative?

Podiatrist Rachel Little is very pleased with her new surroundings in Aberdeen's new Community Health Village.

Instead of being on its own, her clinic is now housed alongside other health services such as physiotherapy.

"It's actually improved things drastically. We can speak to colleagues face-to-face if we receive a referral and we're questioning something - we can just nip through and see them," she said.

It's not just the proximity to colleagues which has made life better.

Many staff moved from Aberdeen's oldest hospital, Woolmanhill, which dates from 1749. They are now housed in a light and airy building, complete with a coffee shop and pleasant atrium. It is so pleasant, patients have even been turning up early.

Podiatrist Rachel Little said the new building has "drastically" improved communication with colleagues

"Some of the patients from the cardiac rehab classes meet in the coffee area before their classes. It's a nice social element," said Rachel.

Of course, Rachel is not the first member of NHS staff to find herself in a pleasant new building. Over the past 15 years, the NHS has funded a massive building programme, but the way it has been financed has been controversial.

Under Private Finance Initiatives (PFI), the private sector took on the cost of construction and charged the NHS for rent and maintenance.

Some health boards are still struggling with ongoing PFI debts. Worst affected is NHS Lanarkshire which, in 2012/13, had to set aside £50m of its £980m budget for two PFI hospitals at Hairmyres and Wishaw. This financial burden was given by health secretary Alex Neil as one of the factors behind a high mortality rate at Lanarkshire's third hospital, Monklands.

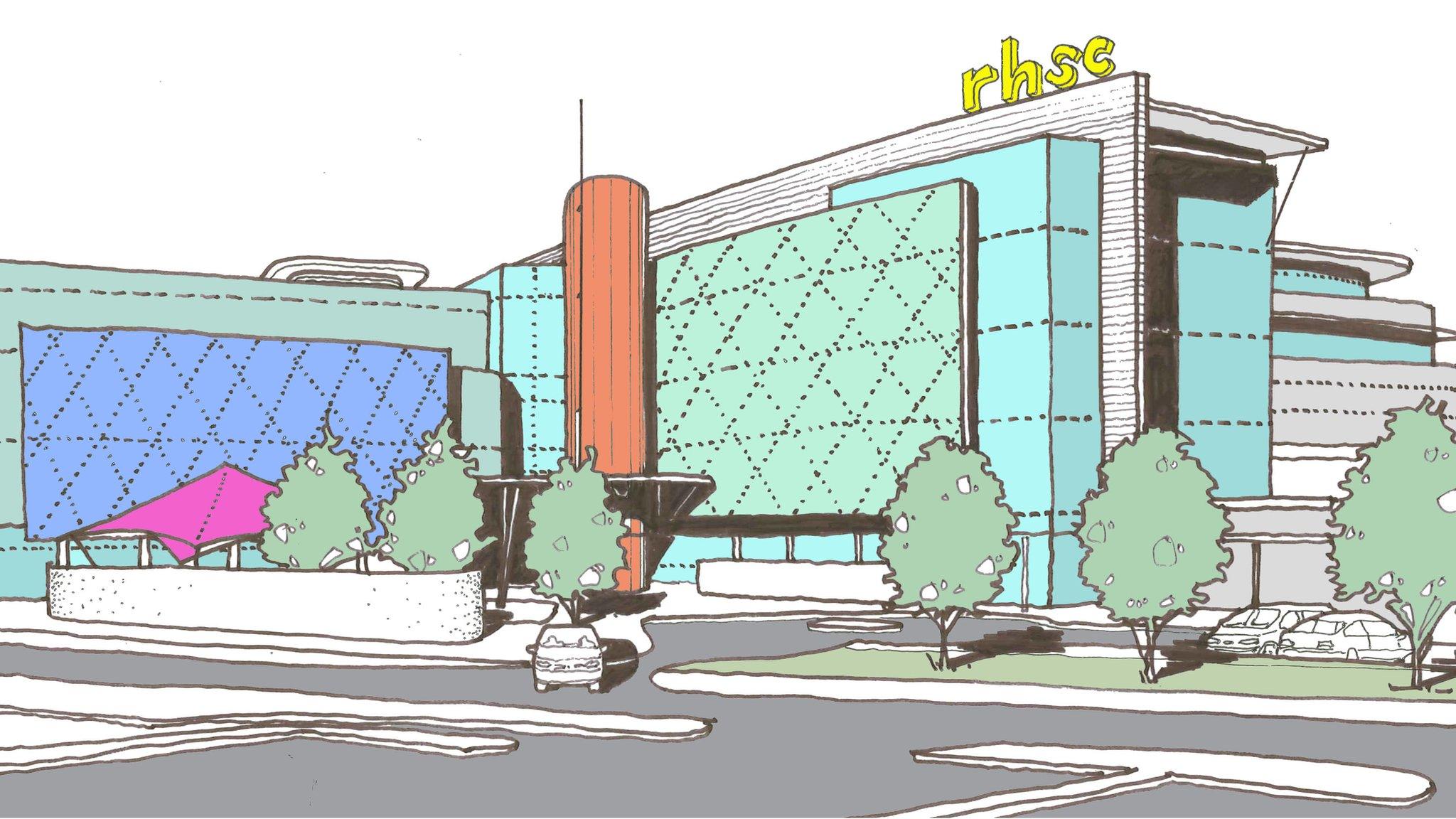

The Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Edinburgh is being built under the Scottish Futures Trust

Aberdeen Community Health and Care Village is the first health project to be built under a new way of financing public projects, overseen by the Scottish Futures Trust.

Also in the pipeline are other major roads, colleges and hospitals, such as the new £150m Royal Hospital for Sick Children and Department of Clinical Neurosciences in Edinburgh.

In some ways the new arrangement is worryingly similar to PFI. The private sector builds the project and the health board pays "rent" for 25 years, but those involved in the new system say there are crucial differences.

"One of the distinct features is that all the participants have an opportunity to invest in the project," said Stan Mathieson who was NHS Grampian's commercial lead for the health village.

"We are a shareholder and we will get returns over the 25 years."

Profit levels are also capped.

Patients seem to like the new "light and airy" surroundings of the Aberdeen Community Health and Care Village

"The 'hub' company is unable to breach the capped rate of return, so they can't make too much money," he added.

Also, unlike PFI schemes, where individual NHS boards were left to negotiate, often disastrous, contracts, the Scottish Futures Trust checks that each project represents value for money.

So far the Scottish Futures Trust has not attracted the vocal criticism levelled at PFI schemes but there are still concerns. The public sector union, Unison, said the essential features of both systems are the same.

"The Aberdeen Health Village and similar 'Public-Private Partnership' schemes are an improvement," said the union's Scottish organiser, Dave Watson.

"However, they still rely on expensive private finance, tie health boards to long contracts and profits are simply pushed down to the contractor level. This means resources that could be spent on better health care are being wasted."

- Published6 March 2014

- Published12 June 2013

- Published19 September 2012

- Published15 December 2011