Asylum seekers detained at Dungavel for more than a year

- Published

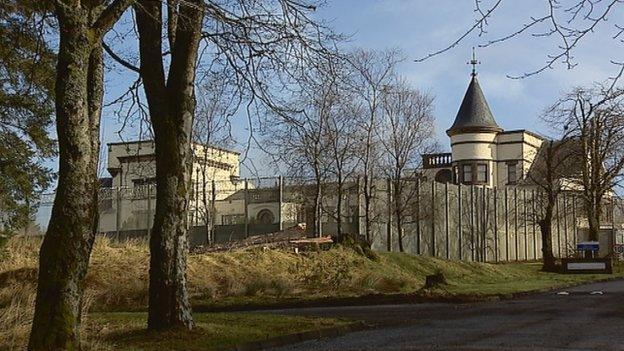

Dungavel is the only immigration removal centre in Scotland

Dozens of asylum seekers have been held at Dungavel immigration removal centre (IRC) in South Lanarkshire for months, new figures released to BBC Scotland reveal.

In some cases detainees were held for more than a year.

The figures come as MPs have called for a limit on the time someone could be detained under immigration powers.

The Home Office said it only detained people for the shortest period necessary.

The figures, released to the BBC's Scotland 2015 programme under Freedom of Information legislation, present a snapshot of detention at the controversial facility outside Strathaven.

On 7 January this year, 41 of the 185 detainees at Dungavel had been held there for more than three months.

Of those, 32 had been detained for more than six months, while in two cases detainees from Western Sahara and Algeria had been at Dungavel for more than a year.

One detainee from Iran had spent 11 months in Dungavel and a total of almost two and a half years in detention.

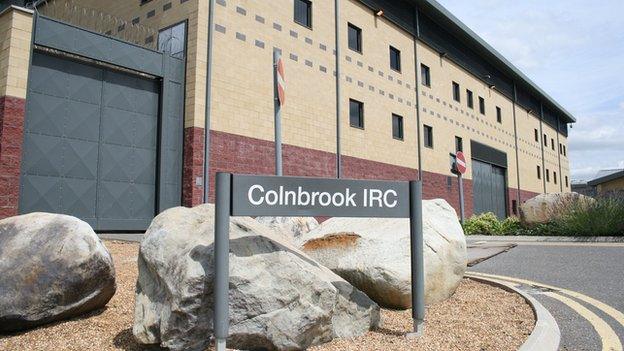

Rather than for criminal charges, asylum seekers and other migrant groups are held in immigration detention to enforce their removal from the UK or while their case is being assessed by the Home Office.

Among the detainees were people from countries to which it is often very difficult to enforce removal.

Countries such as Somalia, Iran and West African states often do not grant travel documents to asylum seekers whose applications to remain in the UK have been rejected by the Home Office.

'In limbo'

Sol - not is real name - was taken to Dungavel after serving a prison sentence for working in the UK illegally.

The Home Office was unable to remove him after his home country disputed his citizenship.

Sol - not his real name - is part of a group of former detainees who speak out about detention

He spent two and a half years in Dungavel, and a total of three and a half years in detention, more than three times as long as his initial prison sentence.

"The difference between prison and detention is that in prison you count your days down and in detention you count your days up," he told BBC Scotland.

"It's mental torture. It's so scary. You don't know when you will be released. You don't know when you'll be deported. You are in limbo."

He said he often saw people struggling to cope with the uncertainty of being in detention.

Sol, who is now effectively stateless, has a case of unlawful detention against the Home Office pending and cannot work in the UK in the meantime.

He is also part of Freed Voices, a group of former detainees who were detained for 20 years between them and who speak out about detention.

Time limit

Currently, the UK is the only country in the European Union which has no cap on the time someone can be detained under immigration powers.

A group of MPs has called for a 28-day limit on the length of time detainees like Sol can be held in Dungavel and other centres across the UK.

It came after they carried out a lengthy inquiry into immigration detention.

The All Party Parliamentary Groups on Refugees and Migrants also said the "enforcement-focused culture of the Home Office" meant that official guidance stating that detention should be used sparingly and for the shortest possible time was not being followed, resulting in too many instances of unnecessary detention.

Lib Dem MP Sarah Teather, the group's chair, said: "The UK is an outlier in not having a time limit on detention. We have concluded that the current system is expensive, ineffective and unjust.

"During the inquiry, we heard about the huge uncertainty this causes people to live with, not knowing if tomorrow they will be released, removed from the country, or continue being in detention."

Mental health problems

Dr Katy Robjant is a psychiatrist who has examined the mental health of detainees who have been held for long term periods of time in immigration detention.

In one of her studies she found that those who were detained for more than 30 days had higher instances of mental health problems than those held for shorter periods.

Dungavel, near Strathaven in South Lanarkshire, opened in 2001

She told BBC Scotland: "Research has shown that long term detention is linked to mental health problems including anxiety, depression and PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder).

"From my clinical experience, clients often report PTSD symptoms that are directly linked to the experience of detention.

"For example, nightmares or intrusive memories about being in detention or about experiences they witnessed while in detention such as seeing other detainees injured whilst resisting removal attempts, seeing other detainees on hunger strike or self-harm."

Campaigners welcomed the MPs' call to end indefinite detention and added that the practice should be stopped altogether.

Jerome Phelps of Detention Action said: "The inquiry is right that it is not enough to tinker with conditions in detention. Only wholesale reform can address the grotesquely inefficient and unjust incarceration of 30,000 migrants a year."

"The UK is isolated in its reliance on enforcement and detention. Detention is not working, either for immigration control or for the people at the sharp end."

'Sense of fairness'

According to the Home Office, the average cost of keeping one detainee in an IRC in 2014 was £97 per night.

Based on these costs, the total spent on detaining those who were in Dungavel on 7 January 2015 would be £1.5m.

In a statement, the Home Office said: "People are only detained for the shortest period necessary and all detention is reviewed on a regular basis to ensure it remains justified and reasonable."

"A sense of fairness must always be at the heart of our immigration system - including for those we are removing from the UK."

"That is why the home secretary commissioned Stephen Shaw to carry out a comprehensive review of our immigration detention estate to ensure the health and wellbeing of all detainees, some of whom may be vulnerable, is safeguarded at all times."

Policy and practice disconnect

Dr Alice Edwards, chief of protection policy and legal advice with the UN refugee agency, UNHCR, said that her organisation appreciated that the government's "quite clear" instructions to immigration officials did indicate there should be a presumption against detention, and that detention should be for the shortest period of time possible.

"What we find is there is a disconnect between the policies and what happens in practice," she said.

"Of course, the failure to have automatic reviews, which are available in other countries, does lead to people sometimes being forgotten in detention."

The Scottish government - whose referendum White Paper insisted an independent Scotland would have banned immigration detention - called for Dungavel to be closed.

Opened in 2001, Dungavel is the only IRC in Scotland. There are 12 other centres across England.

This is not the first time the controversial facility outside Strathaven has received attention.

Previously, children have been held at the centre, and in 2012 a newspaper investigation found that victims of torture had been held at Dungavel, despite this being against Home Office rules, unless in exceptional circumstances.

- Published3 March 2015

- Published12 May 2014