Q&A: Why does immigration matter?

- Published

Recent polls consistently show voters think that immigration is one of the issues people most want to see addressed in the UK general election campaign.

That is true of Britain as a whole, as well as Scotland.

BBC Scotland takes a look at why that is the case, as part of a series called Welcome to Scotland?

Welcome to Scotland?

Why does immigration matter to voters?

Britain is changing. Many more people from outside Britain and outside the European Union have moved to Britain since the start of the century.

In the decade between the last two national censuses (2001 and 2011), the population of England and Wales went up 3.7 million, or 7%. More than half of that was due to migration, some due to the birth rate.

In Scotland, the population rose by 5%.

This was the biggest single-decade increase in a century. The growth rate is expected to continue through the current decade.

Some of the newcomers are refugees and asylum seekers. Some are extremely rich. And many have come from other parts of the EU, from where migration is unrestricted.

Ahead of the economic downturn, Britain saw an unprecedented influx of people, most of them young, from the newer members of the EU, many of them from Poland and the Baltic states.

People can see their neighbourhoods, towns or cities changing and some raise concerns that there are too many immigrants.

That raises cultural fears, but also tensions over allocations of public funding - for housing, welfare and health services.

Concern about immigration over the past 30 years has risen roughly in line with immigration numbers.

The job market has changed over that time. Some people feel more insecure about employment, feeling that their position has been undercut by the availability to recruiters of incomers.

Some critics of uncontrolled EU migration say migrants are securing jobs which could otherwise be done by people already based in Britain.

Who is most unhappy about immigration?

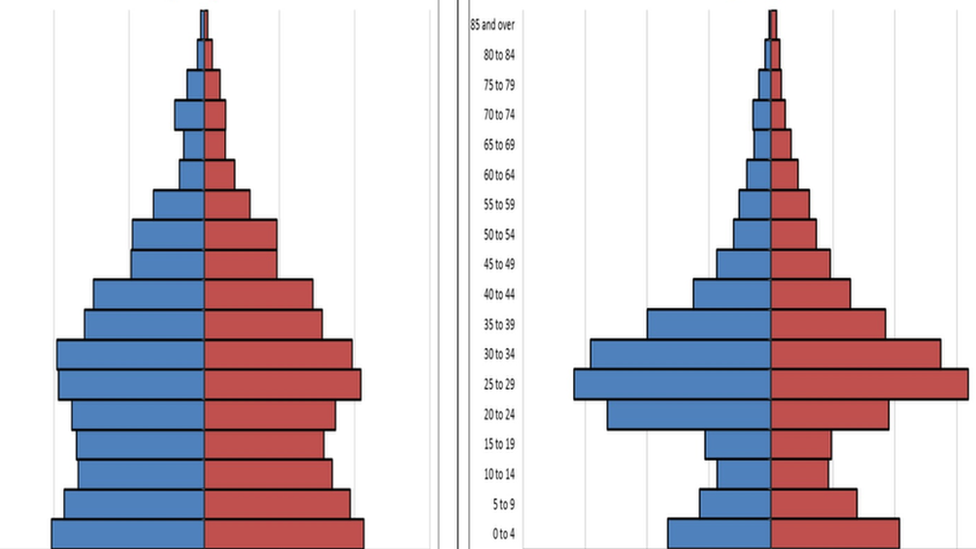

Analysis of polling results by Ipsos Mori found that there is a clear link with age.

It is not only that people born before 1945 were nearly twice as likely to want less immigration than young people, but there is some evidence that people become more opposed to immigration as they grow older.

There is also a link between social class, defined by work and skill level. Professionals and managers are least likely to want immigration reduced, and skilled manual workers are most likely to do so - though the gap is not as clear as for age groups.

Surely those who live with the most ethnic diversity in their neighbourhood, town or city are the ones who are most unhappy about immigration?

That's not what Ipsos Mori found. The areas with the most diversity have lower levels of opposition to it among "white British" people. And even areas seeing the fastest change, as diversity increases, are a bit less likely to oppose immigration than those areas with the least diversity.

For London, for instance, which has seen the most rapid change in recent years, there are only small numbers who want to see more immigration, a quarter think it should stay as it is, and there is a clear majority who want to see less. But the proportion who want to see a lot less is much lower than in other types of city or neighbourhood.

And it is not only "native" British people who want to see immigration reduced, found Ipsos Mori. Of those immigrants who arrived in the UK before 1990, a clear majority think the same.

What's the view of immigration elsewhere?

Ipsos Mori found that British people have been clearly and consistently more concerned about immigration than the average in Western Europe and Scandinavia.

Around the world, with many millions on the move, about 10% of people say immigration is one of their top two concerns. In Britain, it has been around 40% for the past four years.

And compared with other Western Europeans, the British have been far more likely to see immigration as a problem than an opportunity.

One of the reasons which may explain those attitudes is that the British greatly over-estimate the number of immigrants in the country. One poll late last year showed the average guess about immigrants was 24%, where the officially counted figure is 13%.

But immigration is a significant political issue across much of Europe, including France in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attack and in Scandinavia, where integration is creating tensions, partly because some immigrants challenge Northern European liberal attitudes.

What is the political response to it?

As the public raises immigration as a major concern, the question of free movement within Europe has become a hotter issue.

UKIP has raised its support while arguing that it wants to pull out of the European Union, saying this would get back control of the flow of people into the country.

Some Conservatives want the same. And under pressure from his Euro-sceptic MPs, David Cameron pledged to cut net immigration during this parliament.

Recent figures show that has not happened. On the contrary, net immigration has increased.

One reason for that is that there is no control of the number of British people who leave, which is part of the calculation of net migration.

Labour has publicly regretted that it was so open to immigration while in power between 1997 and 2010 - the period when the gates opened to the new Europeans.

It is promising a tougher regime than before, delays for migration of workers from new EU members, making it illegal for UK recruiters only to target people from overseas, and longer delays before immigrants can claim benefits.

In Scotland, there has been a very different debate. While first minister, Labour's Jack McConnell secured a cross-party consensus that Scotland had to turn around its falling population.

He secured, though only temporarily, a Whitehall exception to work permit rules, allowing "fresh talent" - those graduating from Scottish universities - to remain for a short period in Scotland to get work experience.

The SNP government wants to see a similar plan reinstated. Nationalists and some others argue that Holyrood should be able to set its own immigration policy, to meet specific needs.

Scottish Conservatives follow the London line on making it tougher for immigrants to claim benefits.

However, it continues to see the case for Scotland encouraging more in-migration in order to tackle demographic change.

Like Labour, Liberal Democrats want tougher border checks, and emphasise the importance of immigrants speaking English. They would be expected to 'earn' the right to benefits.

UKIP accepts the case for some immigration, but wants net migration below 50,000. It wants to see a points system targeted at high-skilled migrants. It wants to require English language skills, and to deport asylum seekers more easily.

But is the Holyrood consensus in tune with a different set of views across the Scottish public?

That is far from clear, particularly after the McConnell initiative appeared to work, with a rise in the population after it was announced.

The Big Immigration debate is on BBC Two Scotland at 22:30 on Tuesday 10 March

- Published10 March 2015

- Published11 March 2015

- Published10 March 2015

- Published9 March 2015

- Published9 March 2015

- Published26 February 2015