How do we define immigration?

- Published

As part of a series of articles on the issue of immigration, BBC Scotland takes a look at how immigration is defined.

Whether your birthplace, your passport or your ethnicity - immigration can be measured in different ways.

As measures, they all have their limitations.

And as some people often seen as immigrants have been born in a country and have the country's passport, there's no firm definition.

How long ago, for instance, should you or your forebears have moved to Scotland to disqualify you as an immigrant?

And because of your name or the colour of your skin, could you always be seen as part of an immigrant community, even though you may be a third or fourth generation Scot?

Welcome to Scotland?

Those who were born outside Britain can count as immigrants, though their parents may have been wholly British or Scottish but happened to be posted overseas at the time of birth. So that's not entirely reliable as a measure.

Counting those with non-UK citizenship can also be skewed. It can include Scots with dual citizenship, through their parents' different nationalities, or having lived elsewhere and qualifying for foreign citizenship.

And it is likely to include many people who intend to return to their home countries, but are working in this country temporarily. Are these people really immigrants or should they be classified as temporary or migrant workers?

The census asks people to define their own ethnic identity, as well as saying their religious affiliation.

That can be a strong guide to ethnic minorities, but as many of them may be UK passport holders and born in the UK, they don't conform to the conventional definition of immigrant.

And as the census captures population numbers on only one night each decade, it is of very limited use in measuring the flow of people or the duration of their stay.

Net migration

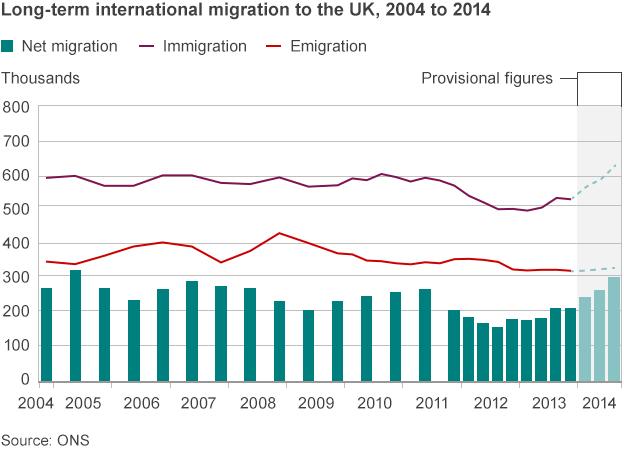

The current coalition government promised to reduce net migration below 100,000. That is defined by the number of leavers for at least a year minus the number of arrivals for at least a year.

However, that policy failed. Net migration has actually risen from 252,000 at the last election to 298,000 in the most recent data - not far off the record level set in 2005.

Partly, that is because the British government is not legally able to restrict the flow of people from the rest of the European Union. And with weak economies in Southern Europe, there is an incentive for many to leave, looking for jobs in countries with stronger economies.

Of course, that includes students, who form a large part of the numbers. Many come from China, with significant numbers also from India, Africa and the US.

It is also because the UK government has no control over the flow of people out of the country. Nor has anyone suggested that it should impose such controls. That number is as important to measuring net migration.

Reversed decline

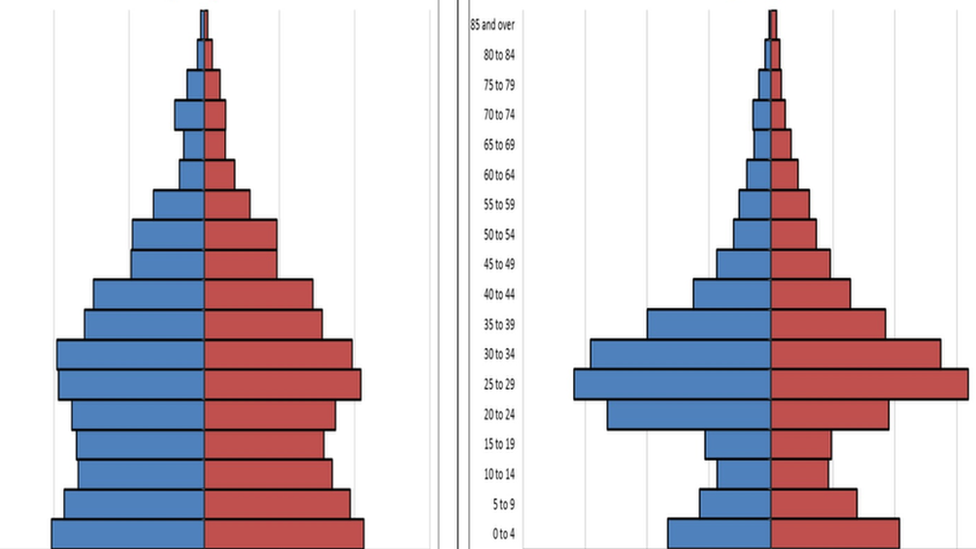

Scotland had long faced net emigration, until recent years. Not only was there an influx from newer members of the EU, but a relatively stronger economy helped boost the number of Scots staying at home rather than leaving for opportunities elsewhere.

In the 1990s, there was net emigration from Scotland, with an estimated average of 3,000 more people leaving than arriving each year.

Last decade, that had turned around to an estimated annual average of 11,000 more arrivals than departures, with the peak of new arrivals in 2005.

The Oxford University Migration Observatory notes that, in 2011, it is estimated 8,000 Scots emigrated to other parts of the EU outside the UK, and 16,000 to non-EU nations.

However, this is perhaps the least reliable form of counting migration, as it relies on a passenger survey carried out at airports.

- Published10 March 2015

- Published11 March 2015

- Published9 March 2015

- Published9 March 2015

- Published10 March 2015

- Published26 February 2015