Penrose Inquiry: The key questions over contaminated blood

- Published

Lord Penrose led the inquiry into NHS use of infected blood and blood products

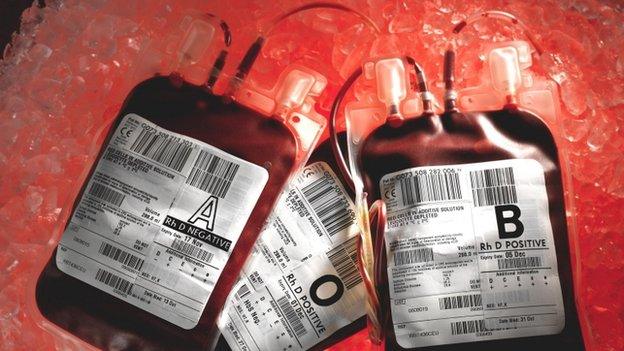

The findings of the Penrose Inquiry, external into the contamination of blood supplies in the 1970s and 80s have been published.

Thousands of people were infected with Hepatitis C and HIV through blood transfusions and blood products.

The inquiry, led by a former High Court judge, has taken six years and cost about £12m to complete.

Why was the inquiry established?

Lord Penrose did not have the power to summon witnesses from outside Scotland

Between 1970 and 1991, thousands of people were infected with Hepatitis C and/or HIV through blood products supplied by the NHS.

The total number of victims is not known, but the Department of Health recently estimated it was 30,000 UK-wide.

There are many unanswered questions surrounding this public health disaster. An inquiry was a key election promise of the SNP and was announced in 2007 when the SNP came to power.

However, there was then a delay of nearly two years before the inquiry opened - a delay which was criticised by a senior Scottish judge.

This is the first statutory inquiry in the UK - one with the power to force witnesses to give evidence.

However, Lord Penrose did not have the power to summon witnesses from outside Scotland. This is a major limitation, since health policy before 1999 was controlled by Westminster and many crucial decisions were made by England-based politicians and civil servants.

What is Hepatitis C?

Hepatitis C is a virus which damages the liver.

In the early stages most people are unaware they have the infection, and between 15-25% of people will clear the virus from their system naturally.

For the remaining 75-85%, their health will gradually deteriorate. They may suffer jaundice, drowsiness, and pain.

Drug treatments are effective in just over half of all cases, although new drugs are offering more effective cure rates.

Twenty years after infection, approximately 15% to 20% of the remaining patients will develop cirrhosis or advanced liver disease, which is fatal without a liver transplant.

Those infected with HIV as well as Hepatitis C develop cirrhosis sooner and have a higher risk of death.

What are the key questions?

The first big question is whether the authorities did enough to protect people from becoming infected.

Children being treated at Yorkhill Hospital in Glasgow for haemophilia were given plasma products sourced from paid donors in the US which were known to be high-risk. As a result, most were infected with HIV and Hepatitis C by the age of five.

Also, the Scottish NHS continued to collect blood from prisoners for two years after it had been told to stop because of the increased risk.

The NHS has always argued that it sought to protect patients in line with understanding at the time - knowledge of HIV and Hepatitis C was still emerging during the 1980s.

The second big question is whether, once the risks became known, enough was done to warn people.

Anyone who has received a blood transfusion before 1991 is at risk of Hepatitis C infection since blood donations were not screened before this date, yet no large-scale public warning has ever been issued.

Early diagnosis is essential for the best chance of successful treatment. Even haemophiliacs who received high-risk clotting drugs were not warned of the dangers for many years - by which time they had unwittingly exposed their partners and family to the risk of infection.

There are other questions which the inquiry won't address: in particular, why have the medical notes of so many of the victims gone missing, particularly the sections relating the crucial period of infection?

What happens next?

Many victims want to see prosecutions, but this is unlikely. Lord Penrose said no individuals or institutions would be held criminally liable as a result of his inquiry.

Three men who contracted Hepatitis C from blood transfusions have already begun a legal case to challenge the support available to them, and it is likely further legal action will follow.

For several years, people infected with Hepatitis C have been eligible for payments from the UK government, depending on the stage of their illness.

The government has always refused to call this compensation, since it maintains it was not to blame for the disaster.

Many victims argue that the payments - of between £20,000 and £70,000 - are insufficient given that, even if they have survived, they cannot get life insurance or a mortgage and many are unable to work.

Earlier this year that view was supported by the All Party Parliamentary Group on Haemophilic and Contaminated Blood, which found many victims were living in poverty and that support arrangements were inadequate.

Scottish Health Minister Shona Robison is expected to make a statement to Holyrood on Thursday. The UK government says it is considering improvements to the support system.

- Published25 March 2015

- Published15 January 2015

- Published8 March 2011