Charles Kennedy: A political contact and a chum

- Published

Former MP Charles Kennedy spoke to the BBC before May's election as part of a behind-the-scenes look at the workings of the House of Commons

Anecdotes and wry observations spilled from Charles Kennedy. He had an acute intelligence and a thoroughgoing comprehension of contemporary politics. But his style was frequently conversational and companionable, rather than didactic or driven.

At the recent Scottish conference of his party, he shared a few yarns in a vintage performance. He recalled the period when he was nearing the end of his career at Glasgow University.

His tutor, apparently, was a mite apprehensive. Young Kennedy was a notably bright chap - but what was he going to do with his ability? Kennedy Jr suggested he might fancy academica or - if all else failed - he could try politics.

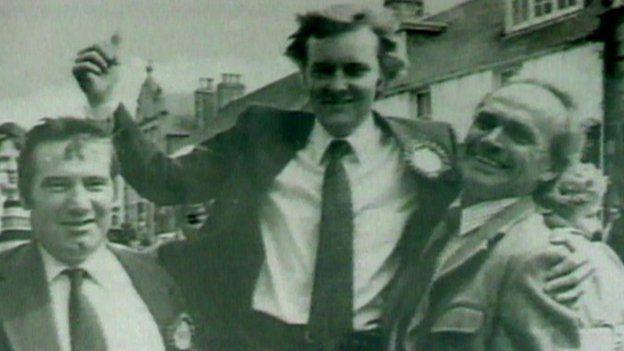

Only a very short time later, he did indeed try politics, standing in a Highland seat against an established and respected Conservative Government Minister, Hamish Gray. To general surprise, Charles Kennedy succeeded, taking the seat at the age of 23.

The response from his erstwhile tutor? He wrote a letter of congratulations, opening along the lines of: "I presume all else failed……"

It was a typically self-effacing tale, delivered with wit and warmth. The then MP followed this by exhorting his party to stick to principles and to continue the fight.

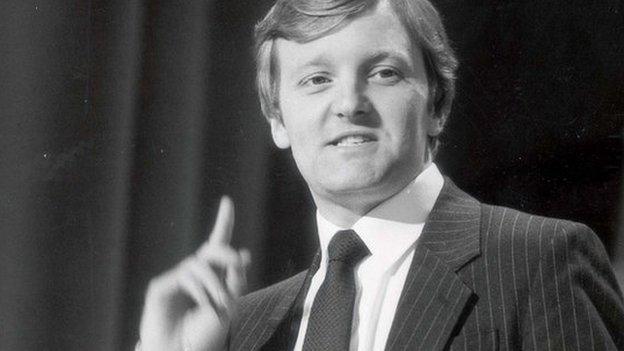

Charles Kennedy speaking in 2003

The then Lib Dem leader appeared on BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs in October 2003 with Sue Lawley.

The politician spoke about his rural upbringing as well as his life in politics. His chosen tunes included fiddle pieces performed by his father Ian at the 1966 Gaelic National Mod and Frank Sinatra's "Fly Me to the Moon" which he said he would like played at his funeral.

As it proved, to no immediate avail. Charles Kennedy lost his Highland constituency in the Commons - along with every other mainland Liberal Democrat in Scotland. He foundered against the rising SNP tide, accompanied by UK wide disquiet with his party following the coalition with the Conservatives.

When a politician dies, the response is occasionally formulaic. Life of service, dedication and duty, will not see the like again.

With Charles Kennedy, the respect is genuine - and the sympathy enormous. After all, this is a man who lost his father (who died in April), who lost his seat in May and who has now lost his life in June.

I first encountered Charles when he entered the Commons as the youngest MP in 1983, making him the Baby of the House. I was a few years older, a correspondent at Westminster for the Press and Journal.

A young Charles Kennedy was in triumphant mood after becoming an MP aged 23

Charles Kennedy was leader of the Liberal Democrat Party for six years

As the P&J reach encompasses the Highlands, Charles was an important contact for me. But he was more. He was a chum. I rated his intellect, his empathy, his humanity and his humour.

He always struck me as slightly removed from politics. By that, I mean politics as routinely practised, politics in conventional form.

Obliged to operate in rigid partisan silos, politicians frequently find themselves resorting to role play like characters from the Commedia dell'Arte, delivering lines and sentiments in keeping with their party's current standpoint, while decrying their rivals as loathsome.

Charles always found all that particularly irksome. If anything, his instincts were journalistic rather than partisan. (I mean that as a compliment!) He could always see the other side of an argument and, instead of shrugging it off, found it mildly amusing to investigate its possibilities.

To be clear, I believe this to be worthy of praise. To be clear further, I do not believe this trait in Charles deflected him from serious involvement in the authentic issues which concerned his constituents and the wider nation.

Might he have done better?

He may have eschewed role play - but he was not playing at politics. He was the real deal, surviving the tensions of merger between the SDP and the Liberals to end up leading the combined operation. Leading it, one should recall, to the party's best performance for many decades.

Might he have done more? Might he have done better? Some certainly feel so. They feel that greater success was on the horizon in 2005, that the political mould was genuinely there for the breaking.

Such comments, it should be said, are most prevalent among those who have never led a party, who have never sought to persuade truculent, vacillating voters to back their side.

Charles Kennedy resigned as leader after admitting to battling a drink problem

And then the flaw. After prolonged speculation, Charles Kennedy confessed in early January 2006 that he had a problem with alcohol, external. He hoped to continue as leader, after a contest, but internal disquiet precluded that. He stood down, never to return to the front benches.

Did the public shun him? Friends, they did not. Not long afterwards, he was mobbed by admirers as he campaigned in the Dunfermline by-election. One young woman shouted: "Charles, I love you". Mr Kennedy advised her, with a wry grin, to beware of the tabloids.

To colleagues, he could occasionally be a source of concern. His drinking. His laid-back outlook. But the sanguine saw the brilliance beneath. The strategists saw the campaigner who was a big hit with the voters.

Charles Kennedy was Rector of Glasgow University, his alma mater, for two terms. The only other two term Rector was Benjamin Disraeli - to whom is attributed the comment: "Damn your principles, stick to your party." Charles Kennedy stuck to his principles.

Sympathy to his family.

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015