The Charles Kennedy Story

- Published

Charles Kennedy, centre, with comedian John Cleese, left, and Paddy Ashdown

Lib Dem leader Charles Kennedy led his party to their best ever election result in 2005 but, battling a drink problem, had to resign a few months later. After his death at the age of 55, here's a look back at the life and career of one of the most influential politicians of his generation.

When they elected Charles Kennedy as their leader in 1999, the Liberal Democrats knew they had chosen a "bon viveur" over rivals with more gravitas but less charisma.

Mr Kennedy was a genial, witty figure more than capable of holding his own on television panel games such as Have I Got News for You.

His laid-back approach contrasted with more earnest, policy-heavy rivals such as Simon Hughes and Malcolm Bruce. Rivals accused him of laziness - one dubbed him "inaction man" compared with his ex-marine predecessor Paddy Ashdown.

But he was no lightweight. He had been one of the brightest of his generation, winning a Fulbright scholarship as well as national debating competitions at an early age and was spoken of as a future leader from his early days.

He was known to be fond of a drink - he described himself during the leadership contest as an "up front social drinker" - and his claim to be trying to give up smoking was already becoming a familiar refrain.

Charles Kennedy: 1959-2015

By Nick Robinson, BBC political editor

Charles Kennedy left a mark on British politics. The man who took his party to its electoral peak, he was the only UK party leader to warn the country of the perils of invading Iraq when Labour and the Conservatives were uniting to support it.

He was also the only Liberal Democrat MP who could not bring himself to vote to form a coalition with the Conservatives.

But British politics also left its mark on him. Elected at the age of just 23, politics and the House of Commons became his life whilst alcohol was his friend, his prop and his curse.

Charles Kennedy's life in pictures

It was even suggested in 1994 that he failed to take politics seriously when he won £2,000 from a £50 flutter betting that the Lib Dems would take only two seats in the European elections.

But Mr Kennedy never seemed worried by such criticism. He knew he was a popular figure among ordinary party members - and his blokeish image won him votes from people normally turned off by politicians.

He also took his politics seriously, had a sharp tactical brain and extensive front rank experience. He was only 39 when he became leader - but he had already been an MP for 16 years and had served in a succession of frontbench roles.

Here is the story of his life in politics.

The early years

Mr Kennedy was born in Inverness and grew up in a remote crofter's cottage in the Highlands. He was educated at Lochaber High School - where at 15 he joined the Labour Party - and Glasgow University.

His father Ian says his son's attitude at school was: "Do enough to get by without knocking your pan in."

This reputation for a laid-back approach to life persisted at university, where his nickname was "Taxi Kennedy" for his habit of taking a minicab for the quarter mile journey from the union buildings to his lectures.

But the young Kennedy also had political ambitions, joining the Dialectic Society, a debating society, and becoming president of the union in 1980 and joining the Social Democratic Party (SDP).

He won an honours degree and a Fulbright scholarship to Indiana University in the US, where he worked on a thesis on Roy Jenkins (one of the founders of the SDP). He seemed set for a career in academia - before agreeing to fight the seemingly no-hope seat of Ross Cromarty and Skye for the SDP at the 1983 election.

Entering politics

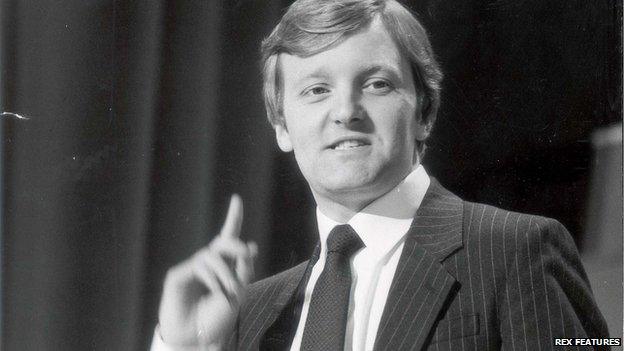

Charles Kennedy in 1983

Mr Kennedy had thought his chances of victory in Ross Cromarty and Skye so slim he had flown back to the US when the polls closed.

But he unseated government minister Hamish Gray and - instead of returning to academia - found himself thrust into the world of Westminster politics at the tender age of 23, as the youngest MP.

As he says in his book The Future of Politics in 2001: "The story begins in the West Highlands of Scotland in November 1959 and I cannot tell you where it might yet end. My first visit to London was not until the age of seventeen; my third visit was as a newly elected Member of Parliament in 1983. A friend put me up, in those first few crazy weeks, in his spare bedroom in Hammersmith. I didn't know how you got to Hammersmith from Heathrow airport. I had no idea where Hammersmith stood geographically in relation to Westminster. It was a fast learning curve."

Charles Kennedy was a backer of the SDP-Liberal Party merger

At first he was SDP spokesman on social security, Scotland and health and when most of his party merged with the Liberals to form the Lib Dems in 1988, he continued to hold a series of frontbench posts.

He made his first major breakthrough in 1990 when he was elected to the crucial post of party president.

Charles Kennedy, right, party president, with leader Paddy Ashdown in 1993

Becoming leader

During the 1990s, Mr Kennedy built his profile through TV appearances, earning him the nickname - which he hated - of "Chatshow Charlie".

In 1999, he beat off five competitors to take over as party leader, gaining 28,425 votes to second place Simon Hughes' 21,833.

He said he wanted to make the Liberal Democrats a party of government, by building its strength on local councils and in the devolved administrations of Scotland and Wales.

On the national stage, he pledged to form policies that would appeal to both Conservative and Labour voters.

Break with Labour

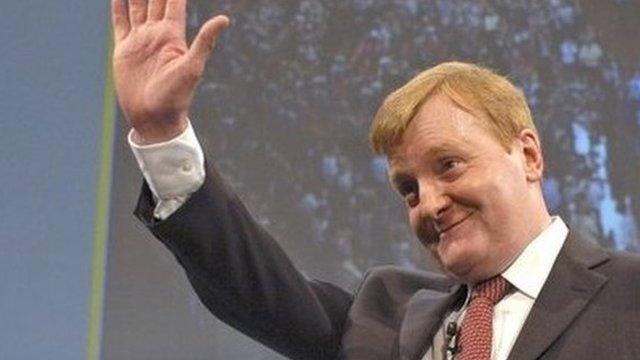

Charles Kennedy at the 2000 Lib Dem conference

Mr Kennedy supported predecessor Paddy Ashdown's attempts to form an alliance with the Labour Party, based around a shared commitment to electoral reform and Europe.

But as soon as he became leader he set about uncoupling the party from Labour, which was now in its New Labour pomp, instead forming distinctive policies on taxation, the environment and, as Labour's enthusiasm for the single currency cooled, Europe.

At the 2001 general election the party improved its share of the vote to 18.3%, 1.5% more than in the 1997 election.

Although smaller than the 25.4% share the SDP/Liberal Alliance achieved in 1983, the Lib Dems won a best ever 52 seats, compared with the Alliance's 23.

Family man

Charles Kennedy and Sarah Gurling in 2001

Mr Kennedy's 2002 marriage to Camelot public relations executive Sarah Gurling - party finance chief Lord Razzall was best man - was seen by many in the party as a sign he was settling down.

The birth of his son in 2005 was seen as a further sign that the hard-partying Kennedy - one commentator had dubbed him "Jock the lad" - was being transformed into a family man.

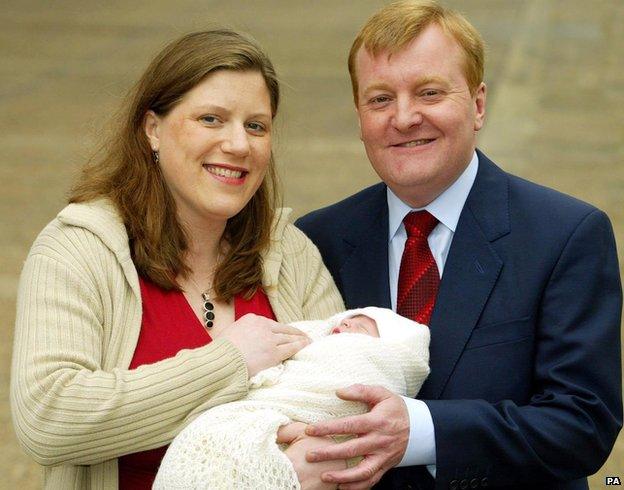

Charles Kennedy, wife Sarah and baby son Donald

Their marriage ended in divorce in 2010, with the Daily Mail reporting that it was "entirely amicable" and in a blog posted, external after Kennedy's death his longtime friend Alastair Campbell describes him as having been "a doting Dad".

Opposing Iraq

Many think Kennedy's finest political hour was his decision to oppose the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq.

It was a decision he had agonised over and he backed British troops once the invasion was under way.

But in the run-up to the war Mr Kennedy became the unofficial leader of the anti-war movement - and the main voice of opposition in the Commons as Labour and the opposition Conservatives backed the military action.

Mr Kennedy at the anti-war protest in Hyde Park, 2003

It was seen by many as a principled stand that was borne out by events when it turned out the intelligence suggesting Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction had been wrong.

It attracted support from Conservative and Labour voters disaffected by their parties' support for the war.

Liberal Democrats fully expected to reap the electoral rewards at the 2005 general election.

Record election result

Mr Kennedy fought the 2005 election as "The Real Alternative", attempting to pull off the difficult task of appealing to both Labour and Tory voters.

The party was rewarded with 22% of votes and 62 seats - the highest tally for a third party since the old Liberal Party days of the 1920s.

But there was a feeling of deflation among some MPs - particularly some of the recent intake on the right of the party who were impatient for power.

The party's 2005 autumn conference was billed as a "celebration" of electoral gains - but ended with Mr Kennedy battling to silence growing criticism of his leadership.

Drink problems

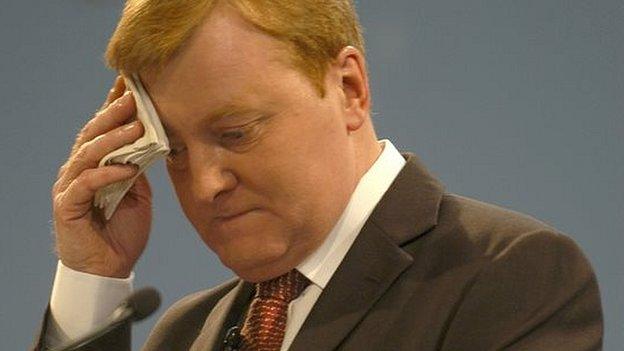

Charles Kennedy at his party's 2005 conference

Mr Kennedy was a familiar sight in the bars and clubs of Westminster for more than 20 years and was known to be fond of a drink.

But whenever he was asked whether he had a problem, he flatly denied it.

After he became the leader, the first time the question of Mr Kennedy's drinking became a mainstream issue was after a 2002 interview with Newsnight's Jeremy Paxman.

"How much do you drink?" Mr Paxman asked. "Moderately, socially, as you well know," was the reply.

Paxman: "You don't drink privately?"

Kennedy: "What do you mean, privately?"

Paxman: "By yourself, a bottle of whisky late at night?"

Kennedy: "No, I do not, no."

Mr Kennedy made several more polite but firm denials over the next few years, sometimes adding a pledge to quit smoking.

In 2004, he said he had cut down on his drinking and was taking more exercise - now it has emerged he was receiving treatment for an alcohol problem.

Concerned colleagues

Despite the public denials, it seems efforts were going on behind the scenes to encourage Mr Kennedy to face up to his demons.

His non-appearance for the 2004 Budget speech, when Vince Cable and Sir Menzies Campbell were reportedly forced to stand in for him at 15 minutes notice led to him having to deny his absence was drink-related.

And a perspiring performance at the 2004 spring conference - put down to a stomach bug - also sparked rumours of alcohol abuse.

Four top party figures apparently cornered Mr Kennedy in his private office in 2004, and insisted he acknowledge his drink problem.

According to reports, they succeeded in persuading him to admit his condition, and he began receiving "private" medical help.

Colleagues in the party apparently expected Mr Kennedy to stand down after the general election in May 2005. As it was the drinking issue only raised its head once during the campaign.

That was when, after a quick paternity leave break during that campaign, he stumbled in an early morning press conference answering media questions on some policy details. He blamed it on a lack of sleep, which any new parent might accept, though others put down to his drinking.

The election was a triumph for the party and he did not resign afterwards, although the rumours grew when in November he pulled out of a scheduled visit to Newcastle while en route. An appearance at London School of Economics also apparently had to curtailed because of drink, it was later claimed.

Political downfall

Charles Kennedy arrives at Lib Dem HQ to announce he is resigning

The election of David Cameron as Conservative leader towards the end of 2005 - and his subsequent appeal to Lib Dem members to jump ship - appeared to throw Mr Kennedy's colleagues into near panic.

They feared the party lacked direction and dynamism, compared with the revitalised Tories.

Senior figures such as deputy leader Sir Menzies Campbell and Simon Hughes told Mr Kennedy he had to "raise his game" or face a leadership challenge.

Mr Kennedy might just have weathered the storm had it not been for journalists from ITV News confronting him with evidence - supplied by senior party colleagues - that he had received treatment for alcohol addiction.

Within an hour of being confronted with detailed allegations, Mr Kennedy made an extraordinary personal statement at party headquarters in Westminster, admitting he had a drink problem.

He threw himself on the mercy of the party membership - among whom he has always been very popular - announcing a leadership contest he intended to take part in.

But his gamble failed to pay off as frontbench figures broke cover to say he should not take part in the leadership contest. More than half of his MPs were openly urging him to quit.

Faced with the threat of a mass walkout by his frontbench team Mr Kennedy felt he had no option but to resign.

On the backbenches

Kennedy returned to life on the backbenches for the Lib Dems - the promise of a return to frontline politics once his drink problem was overcome, never came to pass.

He became a much lower profile figure at Westminster, but never became one of those former leaders who took to criticising their successors in public.

He also resisted the urge, which could have been understood after the criticism he took in 2002/3, of "I told you sos" about the Iraq War as the years passed.

Charles Kennedy with party leader Nick Clegg during the 2010 election campaign

The decision of the party to go into coalition with the Conservatives after the 2010 election was one he was uncomfortable with and he stayed clear of any government role.

This meant he spent the past few years as a more distant figure. Making the occasional speech in the Commons and appearances on TV shows such as a Question Time (although a recent one sparked a fresh round of rumours about his health) and This Week.

Election defeat and life after the Commons

The 2015 election was a traumatic one for the Lib Dems across the UK - and a disastrous one in Scotland as they were hit by their coalition with the Conservatives and the rise of the SNP after the independence referendum in 2014.

Kennedy was one of those who lost their seats as a result, swept away despite him being widely known to be a coalition sceptic and having, in Alastair Campbell's words, taken steps to avoid national Lib Dem figures coming to campaign in his constituency.

After his defeat Kennedy wrote "It has been the greatest privilege of my adult and public life to have served, for 32 years, as the Member of Parliament for our local Highlands and Islands communities. I would particularly like to thank the generation of voters, and then some, who have put their trust in me to carry out that role and its responsibilities."

He said he was "saddened" not to be involved in the devolution of fresh powers to Scotland, but clearly had plans to stay active in politics. Especially, as a passionate pro-European, with the EU referendum to come in which he wished "to be actively engaged".

"The next few years in politics will come down to a tale of two Unions - the UK and the EU. Despite all the difficult challenges ahead the Liberal Democrat voice must and will be heard. We did so over Iraq; we can do so again. Let us relish the prospect."

Tributes

Charles Kennedy appealed to politicians and people across the spectrum with tributes pouring in from all directions after his death. The over-riding theme was respect for his politics and warmth for the man.

Former Labour leader Tony Blair called it a tragedy: "He was throughout his time a lovely, genuine and deeply committed public servant. As leader of the Liberal Democrats, we worked closely together and he was always great company, with a lively and inventive mind."

Former Tory leader Iain Duncan Smith said: "He just had that kind of look of somebody who didn't necessarily appear to be that professional politician. But the point was most of all... for me and for many others was he was a good friend - he was a courteous friend and adversary and always good humoured at the most difficult time."

Current Prime Minister David Cameron said: "He was a talented politician who has died too young. My thoughts are with his family."

Former Lib Dem leader and deputy prime minister Nick Clegg said Mr Kennedy's death "robs Britain of one of the most gifted politicians of his generation", while acting Labour leader Harriet Harman said he "brought courage, wit and humour to everything he did".

And his long-time friend, but also opponent over Iraq War, Alastair Campbell, external, said: "He was great company, sober or drinking. He had a fine political mind and a real commitment to public service. He was not bitter about his ousting as leader. Despite the occasional blip when the drink interfered, he was a terrific communicator and a fine orator. He spoke fluent human, because he had humanity in every vein and every cell."

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published8 May 2015

- Published2 June 2015