How I became a drug cheat athlete to test the system

- Published

Mark's blood was taken once a week and sent off to a lab for analysis

It felt like I had crossed the line. I may not be an elite athlete, but I'm still an athlete. And I had just taken my first shot of EPO.

My goal was not to win a medal or make a team but to test the effectiveness of the athletes' biological passport - the latest tool in the global fight against drugs in sport.

It was a decision I had not arrived at lightly. I had decided to do what no elite athlete could do - put the passport to the test by becoming a doper myself.

For a year I had been investigating allegations about doping in athletics and exploring the cliché that cheats are "one step ahead" of the authorities.

When the biological passport was introduced in 2009, it was seen by some as the saviour of clean sport. Even the disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong said it "worked" and would have prevented him from the using the blood-doping techniques he used to win seven Tour de France titles.

Since 2012, about 50 track and field athletes have been banned for biological passport irregularities. But is that all of them?

And can clean athletes really be sure the passport is levelling the playing field?

THE PASSPORT

EPO is only available in the UK on prescription but it is possible to buy it online

There are different parts to the biological passport but the first one to be introduced, and the one we are interested in here, is the haematological (blood) module of the passport.

EPO, or erythropoietin, is a natural substance produced within the kidneys that stimulates the creation of new red blood cells.

Blood-boosting drugs like EPO, if injected, are only detectable in the urine or blood for a short window of time. The idea of the passport was to move away from searching for the actual drug, to looking for its effects.

The passport requires a series of samples from the athlete, at least four. These are used to establish normal, or baseline, blood values, which are then plotted on a graph. Once the athlete's normal levels are established, natural upper and lower limits are set.

The two most important numbers are the volume of haemoglobin (mature red blood cells) and the percentage of reticulocytes (immature red blood cells). There is also a third key measurement, called the OFF Score, which is a ratio of those two numbers.

Carsten Lundby, one of the world's leading experts on the effect drugs like EPO have on the body, told me EPO increases the amount of red blood cells in your blood stream and it is these cells that carry oxygen to your muscles.

"More oxygen, more power, the faster you go - pretty straightforward, actually," said Lundby.

"The athlete biological passport can indicate that you have performed any type of blood doping. It will show that you have abnormal variations in your blood counts and that something fishy has gone on."

Something "fishy" could be a blood transfusion, or an injection of EPO, but just how "fishy" does it have to be?

Some scientists, including Lundby, have questioned the passport's efficacy - especially when complicating factors like training at altitude are added to the mix - but also its sensitivity to micro-dosing, a little-but-often approach to doping.

The performance benefit of micro-dosing will be smaller, but so too the risk of triggering a red flag.

MY EXPERIMENT

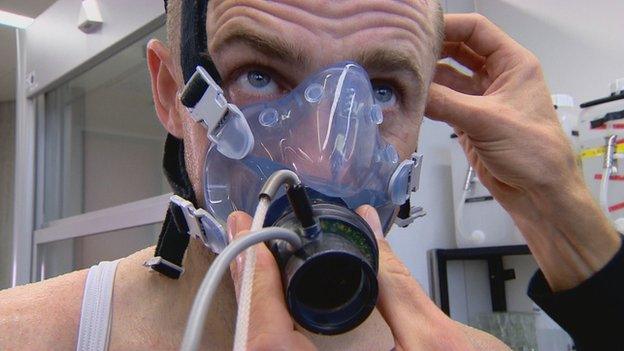

Mark had his fitness measured to supply a baseline for the experiment

I've always been fit, and have competed in dozens if not hundreds of cycling, running, swimming and triathlon races. I've also completed two Ironman-distance triathlons - one of them in under 11 hours - so I'm ok, but would be unlikely to ever trouble a podium.

Even so, I decided I would not compete for the duration of the experiment.

I got myself an experienced coach, Kevin Henderson, who trained me for four months in the run-up to the experiment. I kept up some running and swimming, but concentrated on cycling, both on my indoor bike and on the road, in all weather. I got used to training about 12 hours per week.

The effects were obvious. I was now able to stay with group rides I had previously only seen disappearing into the distance. I even managed a top 10 in one bike race, which was pretty good for me.

So, by the time I was ready to start the experiment, I was fitter than I'd ever been - so I would know that any marked improvements in my performance would most likely not be natural.

Kevin continued to train me throughout the experiment but kept the volume of training the same.

I also immersed myself in the science of blood doping and decided to base my own experiment on studies that had been carried out safely around the world.

It would last for 14 weeks and have three phases. I would have my blood taken once a week and sent off to a lab for analysis. A doctor would monitor my health throughout.

Baseline - weeks 1-3: establish what my "normal" blood levels are. Performance test at end of week 3

Loading - weeks 4-10: undergo a programme of between 2-3 micro-dose injections of EPO per week. Each injection would be supervised. Performance test at end of week 10

Washout - weeks 11-14: critical phase of the experiment, when I stop taking EPO and the passport is meant to be most effective.

The plan was to collect 14 blood analyses and have them put through the biological passport software to see if it would catch me.

But there were two major hurdles still to overcome: I needed the help of an accredited World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada) scientist with access to the passport software, which is easier said than done; and I needed some EPO, which is only available in the UK on prescription, usually reserved for sick people with low blood counts.

I eventually found someone, suitably accredited, within the anti-doping world to run my numbers through the software, but on the condition of anonymity.

So, one problem solved. But without the help of a compliant doctor, where could I get my hands on EPO?

The internet, of course.

My investigation was primarily at the elite end but it does not take a genius to work out that if these blood-boosters, designer steroids and hormones are available online, they will start to filter down into amateur sports.

That is what Andy Parkinson, the former head of UK Anti-Doping, fears. He told me the internet had "dramatically" changed the fight against drugs in sport.

"Ten to 15 years ago, if you wanted to get your hands on a banned substance, you had to physically meet somebody and purchase it off them," said Parkinson.

"Now you can sit at home, go online and order pretty much what you want.

"The really terrifying thing of it is you have no idea what you're buying."

He is right there. I picked a website at random and ordered 10 vials of EPO.

The site appeared to be selling Chinese pharmaceutical supplies but I had to transfer £300 to someone called Tatiana who seemed to be based in eastern Europe. Three weeks passed and a package from China arrived.

Now, it is not strictly illegal for me to be ordering pharmaceutical drugs over the internet for my own use, but I am pretty sure someone, somewhere, is breaking a law since the drugs arrived in packaging disguised as mobile phone covers.

Having sent it to a lab to be verified as EPO, I was now ready to start.

After my three weeks at baseline, I had to undergo a performance test, called a VO2 max test, which measures fitness by calculating maximum oxygen uptake. This involved riding a static bike and gradually increasing the resistance, measured in watts, until I could pedal no more.

Mark underwent punishing tests to measure his performance

To say this is a punishing experience just does not do it justice. I am wired up to a mask, which is difficult to breathe through, and surrounded by a film crew expecting big things.

I managed about 10-and-a-half minutes and a power output of 350 watts. I was almost sick.

I was pleased, though, to score a 58 on the test, which compares favourably to the average person's 35 but rather pathetically against an elite athlete's 70+.

Now that I had posted a "clean" performance marker, it was time to enter the loading phase.

I am not even at the top end of amateur sport but my first shot of a banned drug had an effect on me I was not prepared for: I had cheated for the first time and it felt terrible.

I would not be competing on EPO, and maybe not for a long time afterwards, so none of my competitors would lose out because of what I was doing. But I had cheated and it felt wrong.

I firmly believed what I was doing was in the public interest, though, so I put those thoughts to the back of my mind and got on with the training and with my investigation.

Within a couple of weeks I started to notice a difference, particularly on my longer rides. I appeared to have much more power at the end than I would normally have.

I kept a video diary during this period and one entry tells of a three-hour ride on a dark, cold night, when my legs were sore. It should have been deeply unpleasant, except it wasn't. By the end of the ride, when I should have been wasted, I was as fresh as a daisy. This was to be become a feature.

By week eight, the changes were obvious. I was climbing big hills four hours into a ride as if they were not there.

Like anyone who is into sport, I would usually come home after a good training session and have a great feeling about it. Now I was training at a level I had never reached but there was no joy in it - I knew it was not real.

Very few people knew what I was doing. I had stopped training with friends, and I was constantly wondering about my blood levels and whether my numbers would trigger a red flag on the passport.

I knew the drugs were working - even though I had been taking tiny dosages - because my haemoglobin and reticulocyte numbers were rising steadily but I had no idea if my passport would pass off the fluctuations as normal.

By week 10, I was fairly confident the drugs had given my training a hefty kick but I went back to the lab for another VO2 max test to make sure.

I flew past my previous mark and hung on for more than 12 minutes and 375 watts. This gave me a score of 63, a 7% increase in seven weeks. When you consider that even half a percentage point can make the difference in elite sport, that is a huge bump.

There was no elation. More a weary acceptance of what I had suspected: if you put two people of equal ability up against one another, and one is on drugs, the cheat will almost certainly win.

GETTING AWAY WITH IT

I was now into week 11, the "washout" phase. I was still training but I had stopped taking EPO.

This is the point that real cheats should be most worried because the body wants to reset its blood values to normal, which, if it happens too quickly, can cause a spike in the OFF score, or a dip in the reticulocyte count.

That can trigger a red flag in the biological passport.

I had my blood samples taken as normal, always trying to stay as close to Wada's rules about the samples being analysed within 36 hours.

I sent away 14 samples taken over 14 weeks to my confidential anti-doping source, and these numbers were run through the passport software.

Even though I was half-expecting it, I was still shocked when the result came through. I had passed.

Despite taking EPO for seven weeks, seeing steady rises in my haemoglobin and haematocrit counts, and gaining a significant performance benefit, I was clean.

I am not able to publish the results because I need to protect my source, and I also do not want to reveal anything that could help others cheat, so I went back to Professor Lundby who helped interpret them for me.

He said he could see "traces" of what I had done but "not of a sufficient magnitude to elicit an adverse analytical finding" in the passport.

"There is no evidence that you have injected yourself with EPO," said Lundby.

"If you were an athlete, you would have gotten away with it."

This confirmed my fears that the passport had put a stop to the worst excesses of the Lance Armstrong era but was not sensitive enough to pick up a careful programme of micro-dosing. Lundby was even more alarmed that this had been discovered by a rank amateur.

Lance Armstrong is sport's most famous EPO cheat

"What is worrying to me as a scientist, what's new to me, is that an ordinary guy can look up some information on the internet, do some injections and get away with it," he said.

When I went to Montreal to interview Wada's chief executive David Howman, I put the findings of my experiment to him.

"We certainly know that people try to get to the margins of beating systems and the passport will be no exception to that," said Howman.

"(But the passport) has made a big difference. It's substantially reduced, I would say, over-abuse of some of the blood doping that we knew in the past.

"It's not a panacea. It's another tool in the toolkit, so to speak, and it's used not only to find somebody breaking the rules, (but) also to say: 'This guy's got a profile which is a bit wonky. Go and target-test that guy'."

I have not been back on my bike since my experiment finished.

It had opened my eyes, not just to the difference that taking performance-enhancing drugs could make - there's nothing new in that - but to the ease with which I was able to get away it.

No, I was not subjected to targeted testing, but with drugs like EPO having such a short detection time the testers have to get pretty lucky to get a positive from a urine sample.

I thought the passport was supposed to be the answer but, like Howman told me, it is not a cure for all sport's ills.

And now that I know how effective banned drugs can be, I try to put myself in the shoes of clean athletes who suspect their competitors are doping.

How tough must that be?

If I have learned anything - and if doping is as prevalent as some fear - it is that those athletes who choose to compete clean deserve our utmost respect and admiration.

Maybe I will get the bike back out this weekend.

Catch Me If You Can is available to watch on the BBC iPlayer.

- Published3 June 2015

- Published3 June 2015

- Published5 June 2015