Why the Carmichael case was actually riveting TV

- Published

Lord Matthews and Lady Paton will now consider the submissions they have heard

Judges have retired to consider their position after hearing legal arguments in a bid to unseat Orkney and Shetland MP Alistair Carmichael.

Their conclusion could be of vital importance, in what has been a landmark case - but it may not have made riveting viewing for many.

The case, raised against the Liberal Democrat MP by four of his constituents, was broadcast and streamed online live from the Court of Session in Edinburgh, sitting as a special Election Court.

A broadcast coming live from inside a Scottish courtroom is rare spectacle indeed - but as one online commentator noted, it was hardly an episode of Judge Judy.

There were no sweaty-palmed witnesses, no terse cross-examination, no bewigged lawyers shouted "objection" or paced up and down before a jury.

Even Alistair Carmichael himself wasn't there, leaving matters in the hands of Roddy Dunlop QC while he was at Westminster, carrying on the day job some of his constituents want to see him ejected from.

An initial outburst of enthusiasm and interest on social media turned to bemusement in some quarters as legal precedent from 1886 was cited and minutes of Victorian-era standing committees were pored over.

"Somebody set off the fire alarm," one tweeter implored.

But do not be fooled by the seemingly dull, dry exterior, this was an important moment, made up of important debate.

Mr Carmichael was not in court for the hearing

As Mr Dunlop noted, the potential consequences of this inquiry could be profound.

Not only could it see an MP disqualified from office, it was suggested such cases could even potentially lead to criminal charges, should the Crown choose to pursue them.

And these are not just consequences for Mr Carmichael; the outcome of this case could have an impact on the way all political campaigns are run, and the way the country's political debate is conducted.

Mr Dunlop put it that "we would have to strap future candidates into lie detectors and administer a truth serum".

He also suggested there could be a lot more courts of this kind, rather than one every 50 years - although his opposite number, Jonathan Mitchell QC, said this seemed "highly unlikely".

'Cover up'

This was not a trial of facts; it was essentially a legal debate over the applicability of the Representation of the People Act to the case at hand.

Broadly, the facts of the matter were never in dispute.

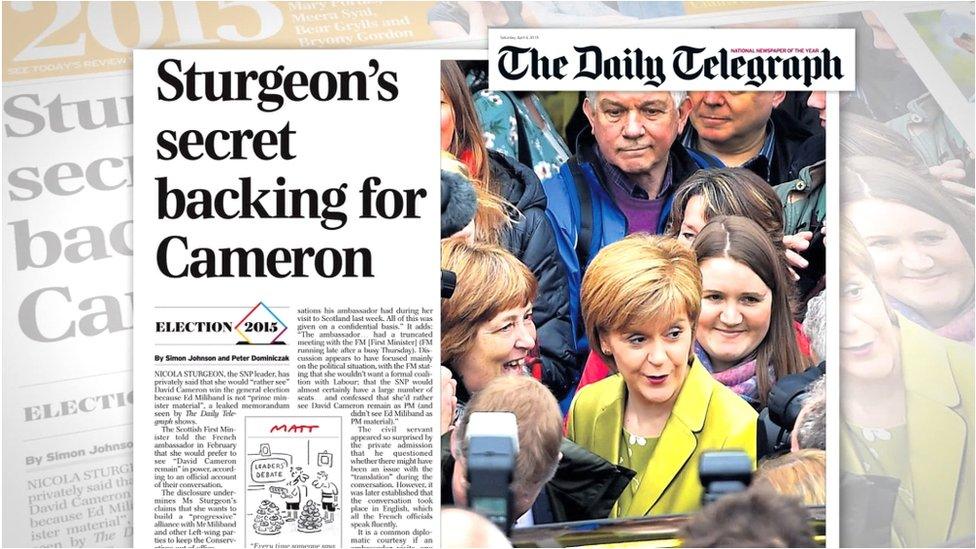

Prior to the General Election, Mr Carmichael sanctioned the leak of a memo about the first minister, then denied doing so in a television interview.

No complaint was raised over the leak itself. It was Mr Carmichael's denial. As Jonathan Mitchell QC, representing the petitioners, put it: "It's not the original sin that matters, it's the cover up."

Roddy Dunlop QC, for Mr Carmichael, said the case was "bound to fail"

Section 106 of the 1983 Act stipulates that a person who, during an election or for the purpose of affecting the return of a candidate, "makes or publishes any false statement of fact in relation to the candidate's personal character or conduct shall be guilty of an illegal practice".

So in the argument of the petitioners, represented by Mr Mitchell, Mr Carmichael's false statement was in relation to his own personal character or conduct, and he was attempting to affect his own return as a candidate by denying knowledge of the leak.

Legal debate

The debate hinged on three distinct points of law.

Firstly, it was contested whether the false statement required by the Act had to be a disparaging remark aimed at another candidate, as Mr Dunlop submitted, or if it could be a "laudatory" talking up of oneself.

Delving into Hansard Parliamentary records, Mr Dunlop said there was a "very clear statement" that the Act was "designed to strike against the disparaging of others", and said it would have been easy for the statute to make it clear if it was meant to apply to candidates speaking of themselves.

However, producing case law of his own, Mr Mitchell submitted that the wording of the Act was wide enough to encapsulate "self-talking".

He said there was "simply no reason to make such distinction" between false statements about oneself or others; "why on Earth", he asked, should they not be equally penalised?

Jonathan Mitchell QC made the case for the petitioners against Mr Carmichael

Secondly, the line between a political attack and a personal one, as defined by the "personal character or conduct" line of the Act, was also debated.

Mr Dunlop said this was a binary position.

He claimed statements are either political or personal, and "it is as clear as clear could be" that what Mr Carmichael said was about politics.

Mr Carmichael was being questioned in his capacity as Scotland Office minister on Channel Four news when the false statement was made.

"We couldn't get a more public or more political context," Mr Dunlop said.

However, Mr Mitchell said Mr Carmichael's denial was a personal matter.

He said it was "fundamentally dishonourable conduct" to leak a secret document, a "wilful and dishonourable breach of duty" beyond politics.

Mr Mitchell said the politician had put his reputation on the line by denying knowledge of the memo.

The QC said nothing in politics, other than the election, called on Mr Carmichael to lie.

Even if driven by political motive, the betrayal of confidence and betrayal of secrets if essentially personal, he said; "no-one goes to the electorate on the platform that 'your secrets are not safe with me'."

The case centres around this Daily Telegraph article from April, based on a leaked memo

The third issue being debated was whether the false statement was made for the purpose of affecting the return of a candidate at the election.

Mr Dunlop said the petitioners had fallen short of proving this motive.

Mr Carmichael's QC also claimed they had muddied the waters by making claims about the election as a whole, while the Act would only apply to an individual constituency poll.

But Mr Mitchell said it was clear that if Mr Carmichael was trying to affect his own electoral chances, he was by extension affecting those of other candidates.

Why did he deny leaking the document, if not to affect the election, he asked?

Avizandum

Having heard two days of complex legal debate, Lord Matthews and Lady Paton declared the case "avizandum", which means they are going to go away and think about it.

Should they back Mr Carmichael on any of the three points, the case could collapse.

A lot rests on their decision; not just in the present case, which could see Scotland's one remaining Liberal Democrat MP ejected from office, and a by-election, but in setting a precedent for future cases.

Their remit as the judges of an Election Court is different to that of a normal Scottish court.

The Election Court is "akin to a committee of the Commons", and reports back to parliament, so there will be careful examination of their own role, as well as the arguments put forward.

Mr Carmichael and his constituents will not be the only ones anxiously awaiting the outcome.

- Published8 September 2015

- Published7 September 2015

- Published1 September 2015

- Published21 August 2015

- Published8 July 2015

- Published6 July 2015