Scots role in gravitational waves discovery

- Published

Albert Einstein predicted the existence of gravitational waves in the Theory of General Relativity

Planet Earth is a shaky old place.

When you're looking for something as subtle as a gravitational wave just about everything else threatens to drown out the signal.

It's what scientists call "noise" - radio signals, passing cars, waves crashing on a distant beach, even fluctuations in temperature.

The Advanced Ligo detectors had to be isolated from all of these noise sources and more. In fact, from everything other than that tiny ripple in space itself.

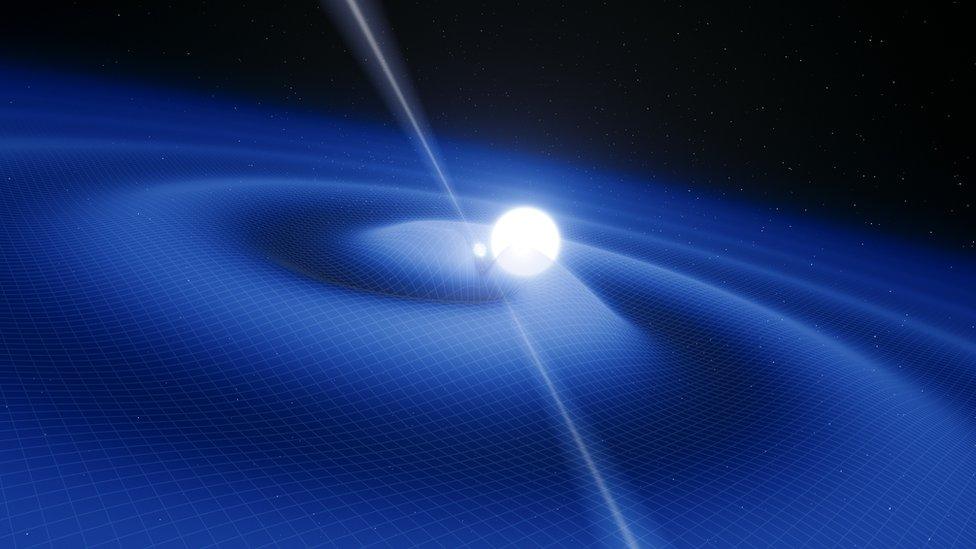

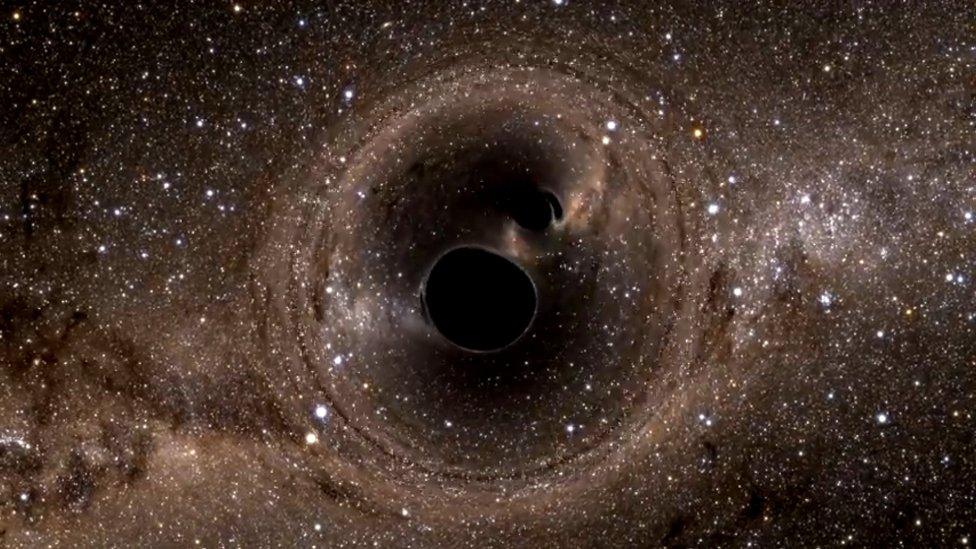

It had begun its journey as a massive wave. When the two black holes collided it had the energy of a hundred billion trillion Suns.

But that was more than a billion years ago, more than a billion light years away.

'Key role'

By the time it passed through the detectors of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (Ligo) in the United States it had the force of a single, not particularly energetic, photon.

In its first incarnation Ligo could not observe anything so puny.

But after an upgrade to Advanced Ligo status the breakthrough was not long in coming.

As befits an international partnership, the discovery was announced at simultaneous news conferences worldwide, including Glasgow.

Measurable gravitational waves should radiate from extreme events like star collisions

Because Scotland - and Glasgow University in particular - has played a key role in the upgrade.

Martin Hendry, Glasgow's professor of gravitational astrophysics and cosmology and a member of the Ligo Scientific Collaboration, explains that this is a two-for-one discovery.

"We've detected gravitational waves directly for the first time," he said, "and it provides us with direct evidence for the first time that black holes exist and can merge together."

They've been looking for gravitational waves at the university for half a century.

James Hough proudly showed his first detector to the cameras of the BBC's Tomorrow's World programme in 1972. It now sits in a glass case at the university.

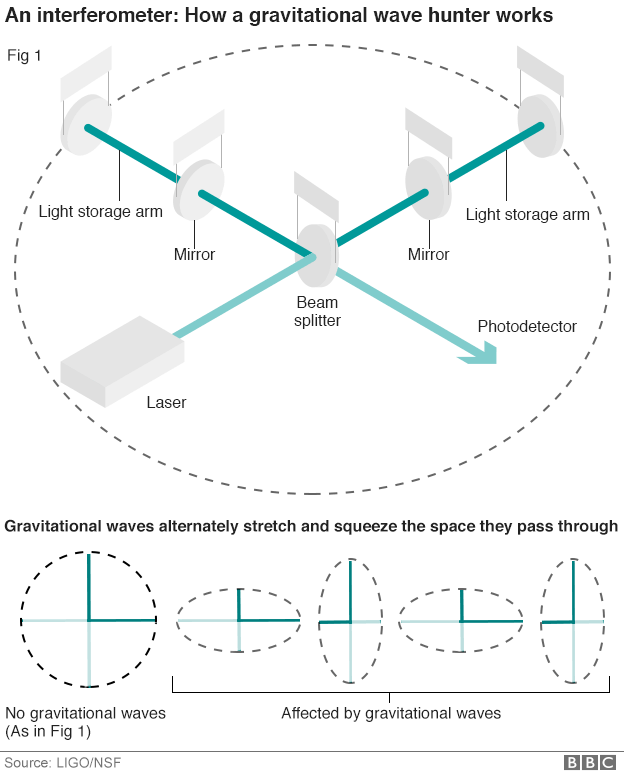

In 2003 Jim - by then Professor - Hough explained to me exactly how Ligo would finally detect the ripples in spacetime. In an interview for Newsnight Scotland he accurately predicted how the passive wave would stretch and squeeze the observatories' laser arms.

Now officially retired, he still contributes to the research effort and was in Washington DC for the announcement of the discovery.

Meanwhile back in Glasgow, Prof Hendry explains how decades of work has borne fruit.

"The disturbance we were looking to measure was going to be about the size of one million-millionth of the width of a human hair," he said.

"That's the change in the separation of the mirrors in our detector.

"The gravitational wave as it passes will stretch and squash spacetime by that tiny amount."

Tiny bends

Other Scottish universities are involved in Ligo - Strathclyde, Edinburgh and the University of the West of Scotland are among dozens of institutions worldwide that have contributed to the effort.

But it's Glasgow university which has led the UK's input to the Ligo upgrade.

"There were certain key aspects of turning it into Advanced Ligo which were led by the UK with Glasgow at the heart of that collaboration," Prof Hendry said.

His colleague Prof Ken Strain led the work to create and install a better suspension system for the mirrors so that our planet's tremors and wobbles could be factored out, the tiny bends in space and time detected, and Albert Einstein proved correct a century after he published his general theory of relativity.

But this is not the end of the story. This is the beginning.

We are witnessing the birth of an entirely new branch of science: gravitational astronomy.

Plans are already in hand to use the waves to look through dust clouds, stars and even galaxies and see what lies beyond.

To gaze across the Universe at things we've never seen before.

- Published11 February 2016

- Published12 February 2016

- Published10 February 2016