John Beattie meets former rugby players with dementia

- Published

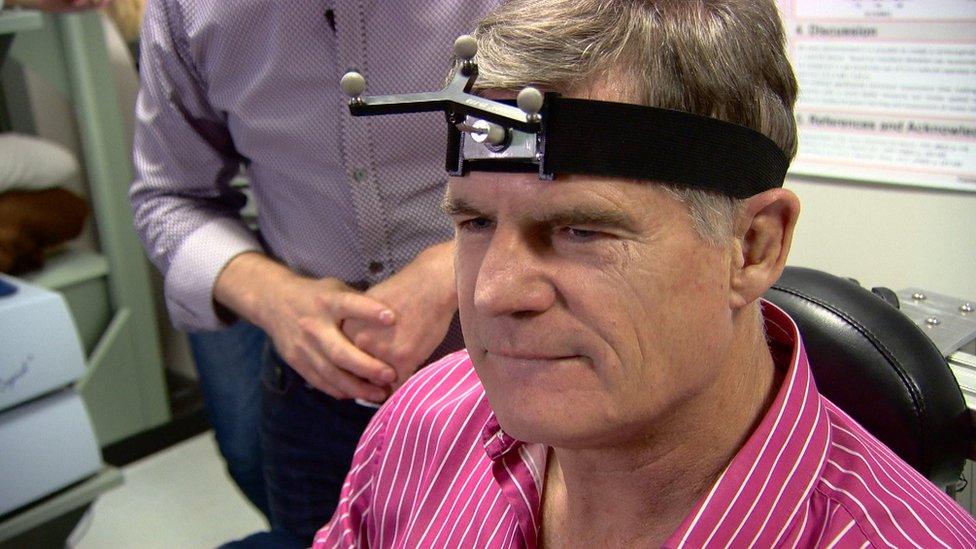

John Beattie met David Shedden, a winger known as "the Spear", who played for Scotland in the 1970s

Former British Lion and Scotland international John Beattie meets ex-players who suffer from dementia and asks whether the condition can be linked to head knocks they received on the pitch.

They arrived gradually - some shuffling in with walking sticks, others ushered in by relatives.

Former rugby players - internationals and club stalwarts - were gathering for a Rugby Memories session. Two of the players were among my heroes.

A single table was set up in a chilly hall at Milngavie's West of Scotland Rugby Club and it was completely covered in images from the game's history.

Team photos and action stills featured many of the greats from the last 50 years.

As the ex-players settled in, relatives and volunteers took them through images and slowly these elderly faces came to life.

Did rugby damage these players' brains?

John Beattie played for Scotland and the British Lions.

Last year he made a documentary about the growing evidence that repeated head injury in contact sports might lead to long term brain damage.

Now he's been contacted by former players worried this may have happened to them.

In this exclusive film he hears their stories and speaks to the man who was the Scotland Rugby team doctor for 30 years.

Former Scotland rugby player John Beattie hears from other former players who fear that their sporting career has caused brain damage

The programme aims to counter the effects of dementia by stimulating memories of great moments in the game.

There were several faces around the table I recognised, but I was here to see one man in particular.

David Shedden was a combative, speedy wing who played for Scotland in the late 1970s.

But in his early 50s he developed dementia. Now he barely speaks and his daughter Lynne said these sessions saw him at his most animated.

She believes his illness may well be linked to the head knocks he experienced as a player. His nickname was "the Spear" given his particular tackling style, and she recounts up to 13 knockouts or concussions suffered by her father during his rugby career.

And she's not the only one. After I made a documentary last year looking at the links between contact sports and brain damage I was contacted by several ex players.

Now three of them feature in a film for the BBC News Scotland website. Their stories are worrying and saddening. As a former player I find it disturbing.

The scientific evidence associating multiple head trauma in a sport like rugby with long-term brain damage is strong and getting stronger.

Work looking at American Football players, as well those in other contact sports, has established that a specific form of dementia called Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) is present in the brains of former players.

Increasingly, the focus is not simply on obviously concussed individuals. Researchers are focusing on the cumulative effects of many small blows to the head sustained not just in matches, but in training.

However, current science can't test for CTE in living individuals, only a post-mortem examination can establish whether it is present.

In the past, little was understood about the potential damage caused by multiple blows to the head.

Mr Shedden's daughter Lynne believes his condition may be linked to the head knocks he received on the field

Former SRU team doctor Donald MacLeod is worried about the long-term effects of rugby on players

For this film I met up with Donald MacLeod. He was the Scottish Rugby Union (SRU) team doctor from 1967 to 1995. He also served as president of the SRU. He is a man who was good to me and I respect him.

He told me he's now convinced that some of the symptoms he saw in players in the past were early signs of CTE brought on by rugby. And he explained he often worries about what the long-term effects of playing have been on players from the '70s, '80s and '90s.

Rugby has done much to improve the treatment of head injuries. Assessment of head injuries on the field and the management of them off it have been transformed.

The SRU told me it was keen to hear from players who are worried they may be having health problems.

Meanwhile, the amazing work of Rugby Memories goes on. It's good to know that the sport these men loved is helping them, even if it's possible that at least some of them are ill as a result of the playing careers that they treasure today.

I would urge rugby players, and their families, to come forward and look for help if they think that there are signs that cause concern.

- Published21 September 2015

- Published21 September 2015

- Published21 September 2015