Ebola nurse Pauline Cafferkey 'stable' after night in London hospital

- Published

Pauline Cafferkey was taken to the Royal Free Hospital in London

Scots nurse Pauline Cafferkey is in a "stable" condition in a London hospital after being admitted for a third time since contracting Ebola.

The 40-year-old from South Lanarkshire was flown south after being admitted to Glasgow's Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

She was put on an RAF Hercules aircraft which took her to London where she was taken to the Royal Free Hospital.

Ms Cafferkey was treated there twice in 2015 after contracting Ebola in Sierra Leone the previous year.

A spokesman for the Royal Free said she had been transferred to the hospital "due to a late complication from her previous infection by the Ebola virus".

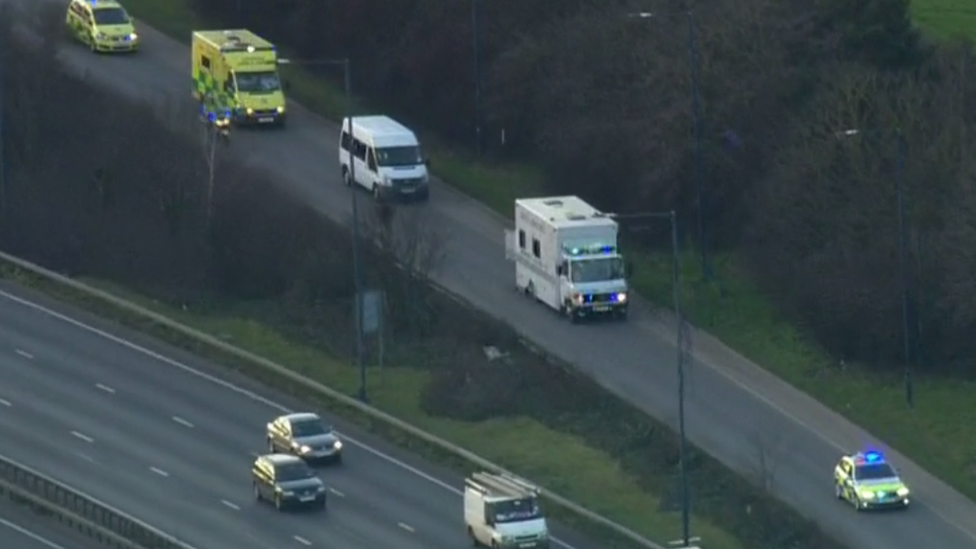

Ms Cafferkey was flown to London from Glasgow Airport in this RAF Hercules

The spokesman added: "She will now be treated by the hospital's infectious diseases team under nationally agreed guidelines.

"The Ebola virus can only be transmitted by direct contact with the blood or bodily fluids of an infected person while they are symptomatic so the risk to the general public remains low and the NHS has well established and practised infection control procedures in place."

Public health

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde said Ms Cafferkey had been admitted to the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital in Glasgow "under routine monitoring by the Infectious Diseases Unit".

The health board said she was "undergoing further investigations and her condition remains stable".

Scottish Health Secretary Shona Robison said: "I'd like to thank the expert NHS staff in Glasgow who have looked after her and helped with her transfer to the Royal Free Hospital, where Pauline has been treated before and where clinicians agreed it would be best to continue her treatment."

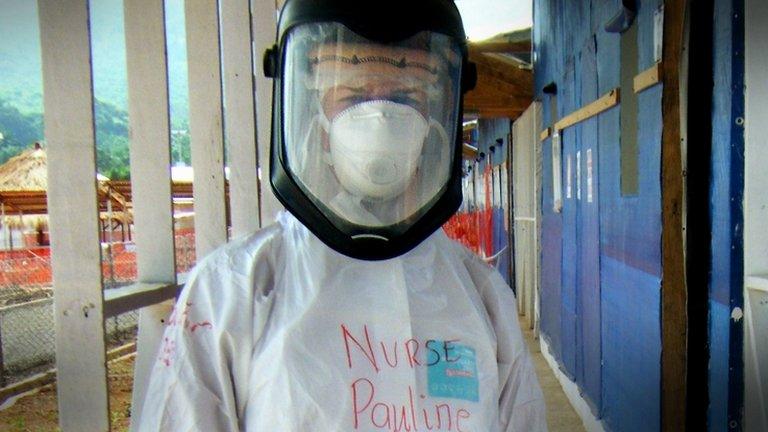

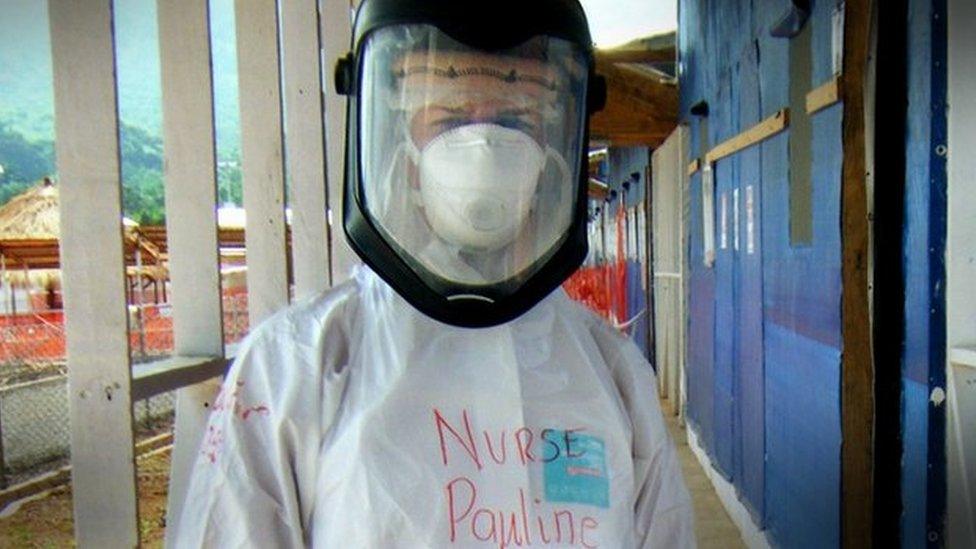

Pauline Cafferkey is in hospital for a third time since contracting Ebola in Sierra Leone in 2014

A RAF ambulance was given a police escort as it transferred Ms Cafferkey to the Royal Free

The nurse, from Halfway, Cambuslang, contracted the virus while working as part of a British team at the Kerry Town Ebola treatment centre.

She spent almost a month in isolation at the Royal Free at the beginning of 2015 after the virus was detected when she arrived back in the UK.

Ms Cafferkey was later discharged after apparently making a full recovery, and in March 2015 returned to work as a public health nurse at Blantyre Health Centre in South Lanarkshire.

In October last year it was discovered that Ebola was still present in her body, with health officials later confirming she had been diagnosed with meningitis caused by the virus.

Ms Cafferkey worked at Kerry Town Ebola treatment centre in 2014

What is Ebola?

Ebola is a viral illness of which the initial symptoms can include a sudden fever, intense weakness, muscle pain and a sore throat, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). And that is just the beginning: subsequent stages are vomiting, diarrhoea and - in some cases - both internal and external bleeding.

The disease infects humans through close contact with infected animals, including chimpanzees, fruit bats and forest antelope.

It then spreads between humans by direct contact with infected blood, bodily fluids or organs, or indirectly through contact with contaminated environments. Even funerals of Ebola victims can be a risk, if mourners have direct contact with the body of the deceased.

Where does it strike?

Ebola outbreaks occur primarily in remote villages in Central and West Africa, near tropical rainforests, says the WHO.

The Ebola outbreak in West Africa was first reported in March 2014, and rapidly became the deadliest occurrence of the disease since its discovery in 1976.

Almost two years on from the first confirmed case recorded on 23 March 2014, more than 11,000 people have been reported as having died from the disease in six countries; Liberia, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, the US and Mali.

The total number of reported cases is almost 29,000.

On 13 January, 2016, the World Health Organisation declared the last of the countries still affected, Liberia, to be Ebola-free.

Ms Cafferkey pictured in Sierra Leone in 2014

Ms Cafferkey was previously treated at a specialist isolation unit at the Royal Free Hospital in London

Bodily tissues can harbour the Ebola infection months after the person appears to have fully recovered.

Dr Derek Gatherer, lecturer in the Division of Biomedical and Life Sciences at Lancaster University, said it was "now becoming clear that Ebola is a far more complex disease than we previously imagined".

He said: "The meningitis that Ms Cafferkey suffered from at the end of last year is one of the most serious complications of all, as it can be life-threatening.

"The other main rare serious complication is inflammation of the eyes (conjunctivitis and/or uveitis) which can lead to blindness, especially if supportive treatments are unavailable."

Dr Gatherer said major post-recovery complications included "joint aches, headaches and general tiredness which can last for months".

Timeline: Pauline Cafferkey's Ebola illness

30 December, 2014 - Ebola nurse Pauline Cafferkey transferred to London unit

31 December, 2014 - Experimental drug for Ebola patient Pauline Cafferkey

4 January, 2015 - UK Ebola nurse Pauline Cafferkey 'in critical condition'

12 January, 2015 - Ebola nurse no longer critically ill

24 January, 2015 - Ebola nurse: Pauline Cafferkey 'happy to be alive'

10 October, 2015 - Ebola nurse Pauline Cafferkey remains 'serious'

14 October, 2015 - Ebola nurse Pauline Cafferkey now 'critically ill'

21 October, 2015 - Ebola caused meningitis in nurse Pauline Cafferkey

12 November, 2015 - Ebola nurse Pauline Cafferkey 'has made full recovery'

23 February, 2016 - Ebola nurse Pauline Cafferkey flown to London hospital

- Published18 August 2016