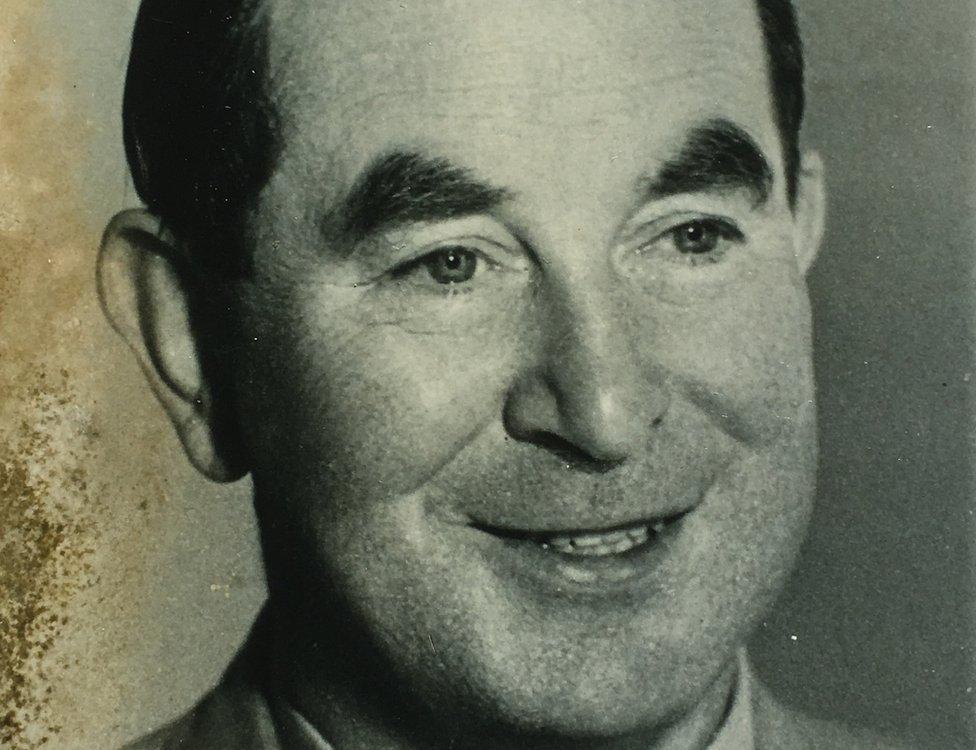

Arthur Woodburn: The man who went from conshie to leader

- Published

Arthur Woodburn became Secretary of State for Scotland after World War Two

Arthur Woodburn rose from being a despised World War One conscientious objector to become Secretary of State for Scotland.

Not many people have made such a leap, but he had the satisfaction of moving up from a tiny, freezing-cold prison cell to the most coveted office in Scotland.

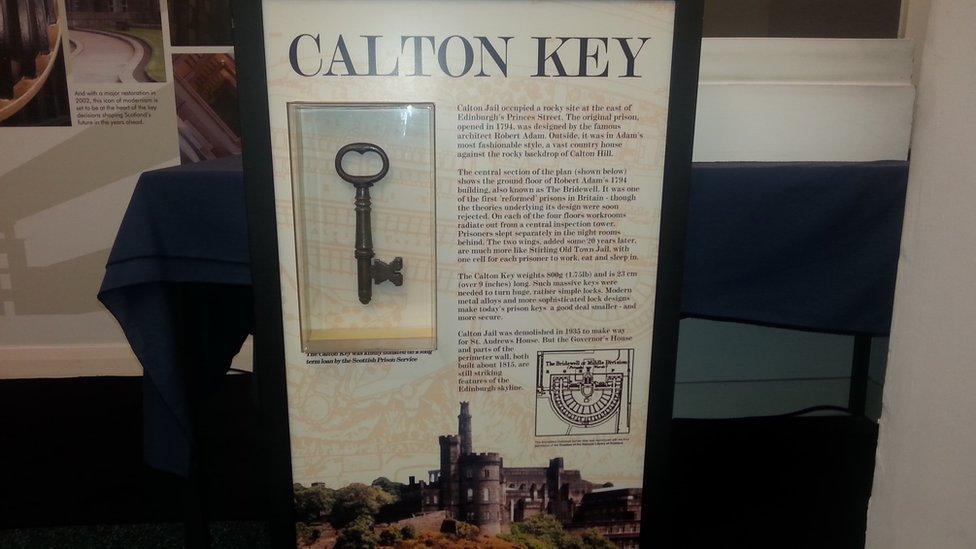

His old prison, Calton Jail in Edinburgh, was razed almost to the ground - and one of Scotland's swankiest 1930s buildings took shape above - St Andrew's House on Calton Hill.

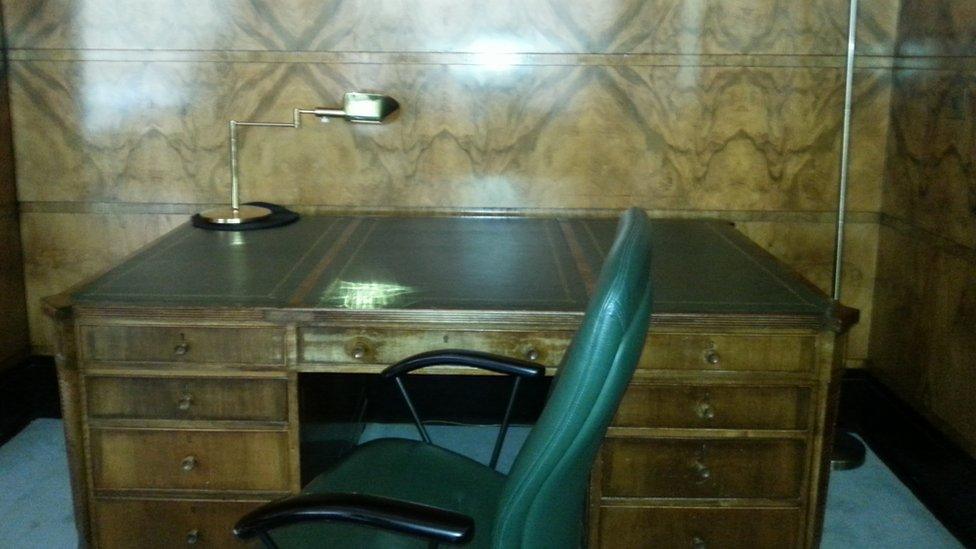

Woodburn's new office when he arrived in 1947 as Labour Secretary of State for Scotland was a walnut-panelled art-deco marvel to die for. But it didn't begin like that.

Arthur Woodburn was born in Edinburgh in 1890, the youngest of eight children.

He did not begin World War One as an objector but his job as a clerk at the London Road foundry showed him how the arms trade worked at that time.

He was appalled that firms were profiting from misery, making huge fortunes while men were fighting at the front losing their lives.

St Andrew's House was built on the site of the old Calton Gaol

It began to turn Woodburn's views and, anyway, he had his elderly mother to look after and a kidney condition that affected his fitness.

An exhibit on Calton Gaol at St Andrew's House

Arthur did not go to war when it began but, in 1916, the war came for Arthur.

The Military Service Act of January 1916 called up all single men between the ages of 18 and 41 unless they were given an exemption by local military tribunals.

Woodburn was 25 and had an easy way out, he was in an exempt occupation that helped the war effort.

But this was too easy for a man with such a strict conscience.

How could he ask others to risk imprisonment for refusing conscription when he had a get-out-of-jail free card?

Woodburn told the authorities in writing that he would resist conscription.

He was now a marked man.

Arthur Woodburn moved from jail to an walnut-panelled office in St Andrews House

There were four categories for exemption - obvious ones for ill health, hardship and essential war work, and then the most controversial one: "conscientious objection to the undertaking of combatant service".

This last category was really for people who had strong religious objections and it did not cover political objection.

Though Woodburn was religious, his anti-war views were deeply rooted in his Independent Labour Party politics, so his chances of escaping call-up were slim.

Those slim chances vanished when a Zeppelin bombed Edinburgh the day before his final appeal.

The Zeppelins were used to drop bombs during the early years of World War One

Soon Arthur was on the path to Calton Jail, which in his case went via Glencorse Barracks, Wormwood Scrubs and even a short stay in the Tower of London before being sent back to Scotland.

Then, as now, trains pulling into Edinburgh Waverley from the east arrived under an impressive set of walls, jutting out of Calton Hill.

They are not there to hold the rocks back or to make it look picturesque for the tourists.

They were built to stop criminals escaping.

A century ago, you would have seen towering above them, not St Andrews House, but the jail Woodburn described as '"the poorhouse of all prisons with the cold chill of a grim fortress".

It was famously cold.

The food was revolting.

According to another conscientious objector it consisted "almost entirely of porridge and sour milk and soup and bread".

"On one day only, Friday, when potatoes are given, can it be called solid food," they said.

And if you were lucky enough to have a hot day in summer, the stench was almost unbearable.

On top of this came the rule of silence.

Prisoners were not allowed to talk to other prisoners.

Then there was hard labour.

In Calton Jail, men endlessly knotted mats until their fingers went into spasms.

The only compensation for Arthur was to be close to family.

He worked out a kind of semaphore system with his wife-to-be, so she could wave at him from Calton Hill and he could signal back that he was all right.

According to Robert Duncan, in his new book Objectors and Resisters, Arthur Woodburn was Scotland's longest serving conscientious objector, from April 1916 to April 1919.

When many others decided to give in and take alternative war work, Woodburn refused.

Finally when the government was slow to release him, he went on hunger strike.

It was a brave stand for his principles.

According to his great nephew Ken Duffy, Woodburn did not forget those principles as he rose up the political hierarchy, but he did change his mind by World War Two about how to apply them.

He decided that only governments, not individuals, would end war.

He hoped they would do that by coming together at last to form a world government.

But he never forgot that his new HQ as Scottish secretary was built on his old jail.

In fact he bought some of the old paving stones from the prison to lay a garden path at his house, a reminder that his path to power was not Old Labour or New Labour but hard labour.

Not many Secretaries of State could say that.

- Published24 February 2014