How Scotland helped sink the Bismarck

- Published

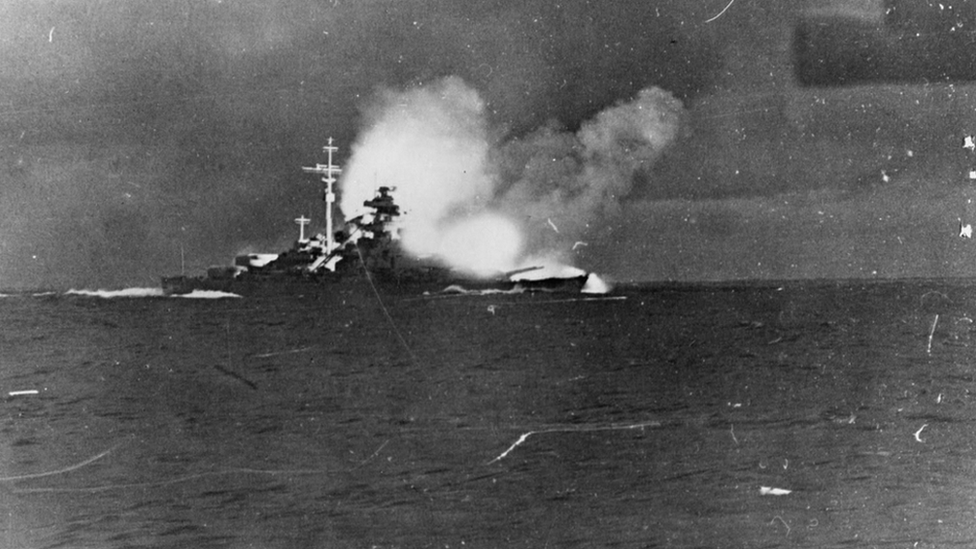

Aerial photo dubbed "The picture which sank the Bismarck," showing the German battleship preparing to leave a fjord near Bergen in Norway

A grainy image taken by a Spitfire pilot flying at 25,000ft (7,600m) led to one of the most significant incidents of World War Two - the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck.

The photograph was taken by Pilot Officer Michael Suckling, 20, flying from RAF Wick in Caithness.

It was one of a number of connections Scotland had with the sinking of the pride of the Nazi navy on 27 May 1941.

British Intelligence already knew that Bismarck on 18 May, which had slipped out of the Baltic Sea, was to be deployed on Operation Rheinübung - an attempt to block Allied shipping.

Ready to go

Secret reports were received from contacts in Sweden and Norway that German battleships had been seen and photographic reconnaissance Spitfires were sent to fly to the Norwegian coast to attempt to locate the ships.

Suckling's photographs, taken as the Bismarck prepared to leave a a fjord near Bergen in Norway, proved the mission was imminent, according to Edinburgh University maritime historian Dr Eric Graham.

"Experts would realise she wasn't refuelling, she wasn't arming.

"They weren't developing booms around her like they did with the Tirpitz when they put her in a fjord. She is ready to go."

Dr Graham added: "Admiral Raeder, in charge of the Kriegsmarine, the German Navy, had this big idea that surface ships, big raiders, would go out and completely disrupt the supply line from America to Britain.

"If it was done in conjunction with submarines, you could win the war."

Once the pictures had been analysed, a naval force was deployed from Scapa Flow in Orkney to intercept Bismarck.

Clyde-built, HMS Hood was the largest warship ever built by the Royal Navy

It was led by the Royal Navy's largest vessel, the Clyde-built Hood, which engaged Bismarck on 24 May in the Denmark Strait, between Iceland and Greenland.

According to Cdr William Sutherland, a board member of the HMS Hood Association, it was an uneven fight.

"The Bismarck was probably the most powerful warship in commission at the time; the Hood was over 20 years old.

"More than that, she was a battle cruiser, rather than a battleship, which meant she had rather less armour than a battleship, particularly horizontal armour against plunging fire - shells coming down from on high at a long range.

"And that proved to be her vulnerability."

At approximately 06:00 a shell from the Bismarck penetrated Hood's armour, exploding her magazines.

She sank in about six minutes with the loss of all but three of her crew of almost 1,500.

From 10 miles away in the Denmark Strait, Bismarck sent up a wall of "plunging fire" which penetrated the weak deck armour of HMS Hood

The Hood's magazines exploded, sinking the Royal Navy's largest vessel in just six minutes

It was a devastating blow to British morale to hear of the loss of a vessel nicknamed "Mighty Hood," which had flown the flag for Royal Navy power around the world through the inter-war years.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill sent a terse signal to the Navy: "Sink the Bismarck."

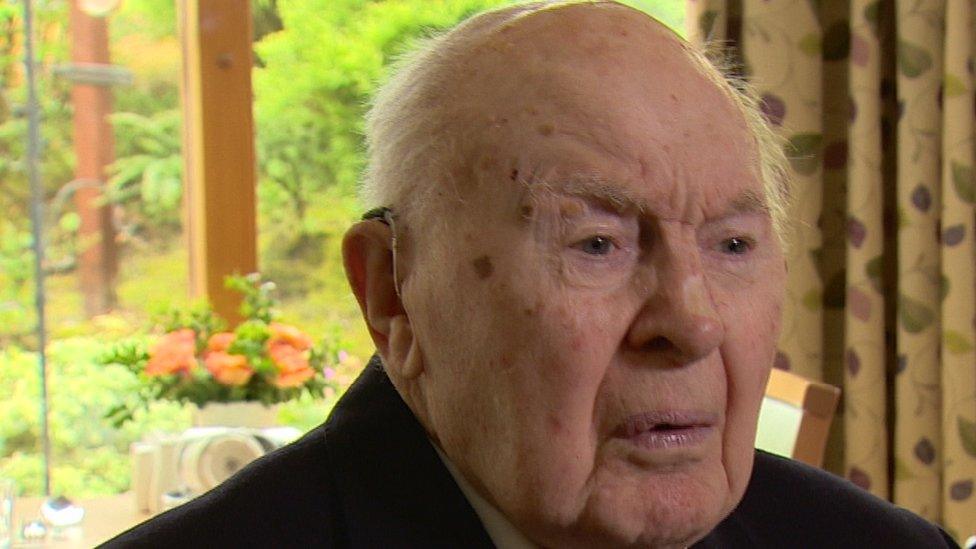

Among those answering that call was John Moffat from Kelso, a Fleet Air Arm pilot with 818 Squadron onboard the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal.

With Bismarck fleeing from the Royal Navy in an attempt to reach the safety of French ports, carrier-based aircraft were the only option to reach her.

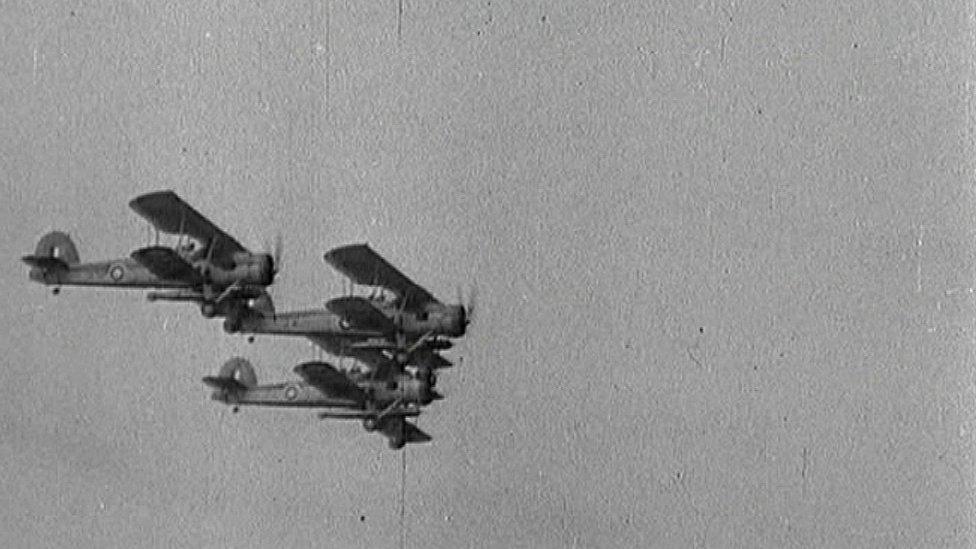

The squadron was equipped with obsolete Fairey Swordfish which were armed by a single torpedo, which limited their top speed to about 150 mph.

Lt-Cdr Moffat, now 96, recalled his first sight of the giant German warship as he descended through the clouds.

"The first sight I had was over my right shoulder. I could see it belching fire from the side of the ship. It's guns. They couldn't fire fast enough."

John Moffat's torpedo crippled the Bismarck

With his observer hanging out of the open cockpit, communicating with him through their headphones, Moffat flew low towards the Bismarck to keep below its guns.

"He kept saying 'Not yet, not yet'. And then eventually he said 'Let her go'.

"I pressed the firing pin on my throttle and the torpedo dropped into the sea.

"And it was him who said 'We've got a runner, Jock'!

Obsolete Fairey Swordfish biplanes, each armed with a single torpedo, attacked Bismarck

That torpedo disabled Bismarck's rudder. Unable to flee, it was caught by the pursuing Royal Navy force and shelled before it was scuttled.

John Moffat, on a second attack of the giant battleship, saw it happen.

He said: "The Bismarck turned on its side, and all the sailors seemed to be in the water. It's lived with me for a long time."

Fewer than 120 of the Bismarck's crew of 2,200 survived.

For Churchill, it was revenge for the sinking of the Hood, and he ordered the photographs taken by Pilot Officer Suckling from RAF Wick to be published under the title: "The pictures that sank the Bismarck."

- Published24 May 2016