'This piece of work alarms me the most'

- Published

The university said it was yet to investigate whether repeatedly heading a football had long-term effects

It's the unexpected nature of the test results that make them so devastating for football.

None of the academics themselves thought that the mere act of heading a normal football a number of times, at a normal speed, as if in a normal situation, would give rise to an immediate reduction in brain function, and the onset memory loss, in the brains of two thirds of the participants tested.

Disturbingly the symptoms took 24 hours to clear. The question that popped into my head was: what if someone does this every day? Do they live a life in a permanently sub concussive state? How does this affect them in older life? What about youngsters whose brains are more prone to damage?

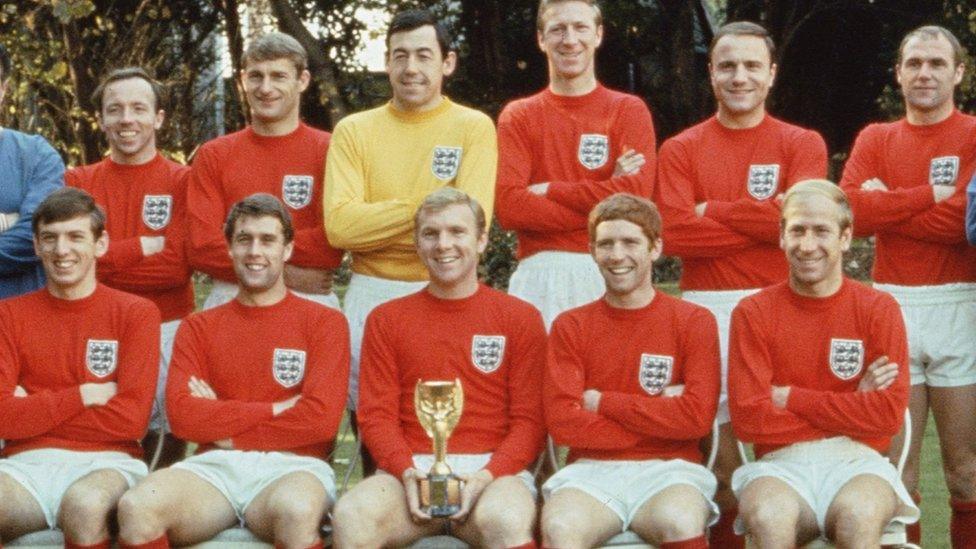

Oh we know about concussions, but we thought the days of heading an old, sodden, leather football were gone. We know about elbows and head knocks, and we know about footballers and rugby players with early onset dementia.

But we didn't know that just heading a ball caused so much damage to the brain.

As I looked on slightly alarmed, a student footballer sat strapped to a chair in the shiny white laboratory of the Cottrell building on the leafy Stirling university campus. Outside the trees tried to discard their summer green for the stunning autumn gold, but the subject's face clung on to the olive tones of someone more than slightly nervous.

Wires led from his body to a machine measuring his brain's ability to react to a stimulus and transfer it to his leg muscles. To my left was a wavy line on a screen that couldn't lie.

The test was a mock-up for our filming, but the source signals going through his brain and to the machine were real and each one came with a crack, a two-eyed blink, a violent contraction of his quadricep, and a tell-tale jump in the trace signal on that all knowing screen.

Putting students through this before and after headers demonstrated the immediate effects I mentioned earlier.

I played rugby, I have a son who plays rugby, and a daughter who plays international football. I hope beyond hope that this test doesn't mean I have been a fool to encourage both of them into sport.

But this, of all the research I have seen, is the piece of work that alarms me the most.

More and more research is pointing to the fact that the bit of my body I was least worried about hurting by taking up sport - my brain - might just have been the most vulnerable after all.

And after this, many footballers young and old will be thinking the same.

More research is needed to assess whether this is temporary, and the effects on youngsters.

- Published24 October 2016

- Published12 April 2016

- Published31 May 2016

- Published19 March 2012