Heading footballs 'affects memory'

- Published

The university said it was yet to investigate whether repeatedly heading a football had long-term effects

Heading a football can significantly affect a player's brain function and memory for 24 hours, a study has found.

Researchers said they had identified "small but significant changes in brain function" after players headed the ball 20 times.

Memory performance was reduced by between 41% and 67% in the 24 hours after routine heading practice.

One of the study's authors suggested football should be avoided ahead of important events like exams.

The University of Stirling study was published in EBioMedicine.

It is the first to detect direct changes in the brain after players were exposed to everyday head impacts, as opposed to clinical brain injuries like concussion.

Researchers fired footballs from a machine designed to simulate the pace and power of a corner kick and asked a group of football players to head a ball 20 times.

The players' brain function and memory were tested before and after the exercise.

Study co-author, neuropathologist Dr Willie Stewart, was asked what advice he would offer to footballers, based on his findings.

He said: "I think this evidence so far suggests - that if it's just a short term thing and it's just something that lasts 24 hours - I think if I were a parent of a kid who had an exam on a Wednesday, I would suggest to them perhaps that they miss football training [on Tuesday] certainly because I would want to do well in that Wednesday afternoon exam."

He added: "If you translate the evidence we've got now, we've got an immediate impairment of short and long-term memory - which does recover.

"It takes 24 hours to recover - so I would say, for that 24-hour period, if you've got something important coming up, that you shouldn't be playing football."

'Industrial disease'

The university said it was yet to investigate whether the changes to the brain were temporary after repeated games of football or if there were long-term consequences on brain health.

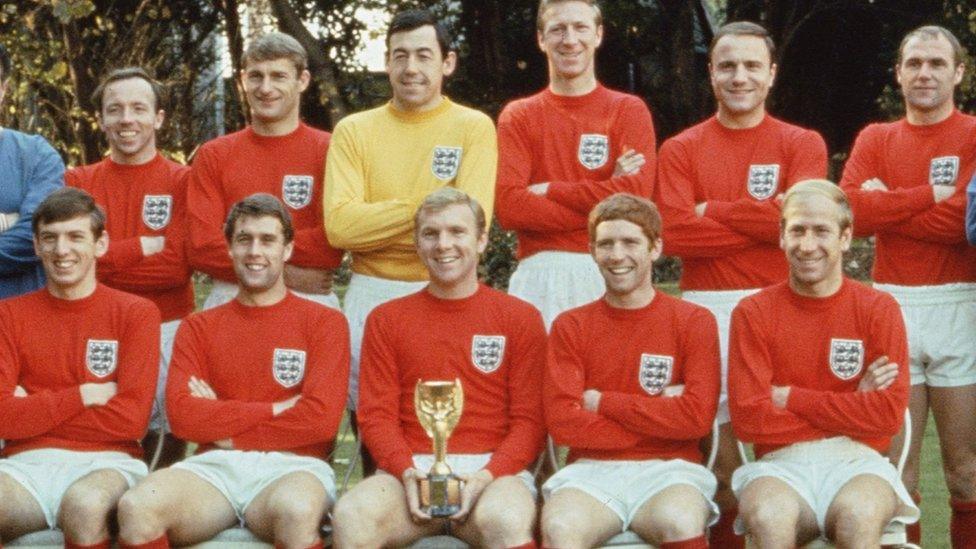

In May this year, the Football Association said it would lead a study into possible links between football and brain diseases.

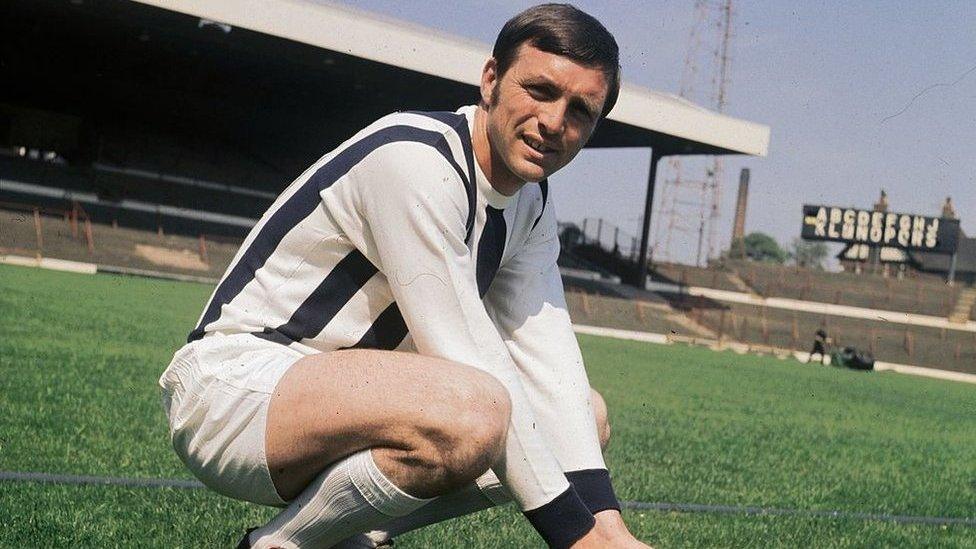

The announcement followed a campaign by the family of former England, West Brom and Notts County striker, Jeff Astle, who died from brain trauma in 2002.

A coroner described his illness as an "industrial disease", in reference to him heading leather balls.

Dr Magdalena Ietswaart, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Stirling, said the research had been carried out in the light of "growing concern" about links between brain injury in sport and the increased risk of dementia.

"Using a drill most amateur and professional teams would be familiar with, we found there was in fact increased inhibition in the brain immediately after heading and that performance on memory tests was reduced significantly," she said.

"Although the changes were temporary, we believe they are significant to brain health, particularly if they happen over and over again as they do in football heading.

"With large numbers of people around the world participating in this sport, it is important that they are aware of what is happening inside the brain and the lasting effect this may have."

Former SFA chief executive Gordon Smith said Scotland should look at the rules in America

Former Scottish Football Association chief executive Gordon Smith said Scotland should consider copying the American method by putting a ban in place to prevent youngsters heading the ball.

He said: "I do consider that it should be looked at for young players below a certain age. In football, for youngsters these days the ball is often in the air because they play smaller-sided games.

"We should try and discourage it from certain age groups in order to make sure there isn't any later effects on little kids."

But he added that if he had his time again, he would still play in the same way: "I think if I was given the choice to play again with the scenario that you were heading the ball and it could do some sort of damage, I would still agree to play.

"That was what I wanted to do more than anything in my life."

Analysis from BBC Radio Scotland's John Beattie, a former international rugby player

It's the unexpected nature of the test results that make them so devastating for football. None of the academics themselves thought that the mere act of heading a normal football a number of times, at a normal speed, as if in a normal situation, would give rise to an immediate reduction in brain function, and the onset memory loss, in the brains of two thirds of the participants tested.

Disturbingly the symptoms took 24 hours to clear. The question that popped into my head was: what if someone does this every day? Do they live a life in a permanently sub concussive state? How does this affect them in older life? What about youngsters whose brains are more prone to damage?

Oh we know about concussions, but we thought the days of heading an old, sodden, leather football were gone. We know about elbows and head knocks, and we know about footballers and rugby players with early onset dementia.

But we didn't know that just heading a ball caused so much damage to the brain.

Read more of John's analysis.

Psychology professor Lindsay Wilson from Stirling University said: "There's been scepticism about whether there is a connection between soccer heading and changes in the brain, but this is evidence of both changes in inhibition and also in cognition immediately after heading.

"I think that together with evidence from previous studies it begins to paint a picture that raises concerns.

"What we really need here is more research to try and better understand what is going on."

When asked about the impact it could have on memory, Prof Wilson said: "The effects we are seeing are rather short term. We really need to identify in more detail what exactly is happening and how long these effects are lasting."

Dr Angus Hunter, reader in exercise physiology, added: "For the first time, sporting bodies and members of the public can see clear evidence of the risks associated with repetitive impact caused by heading a football.

"We hope these findings will open up new approaches for detecting, monitoring and preventing cumulative brain injuries in sport. We need to safeguard the long-term health of football players at all levels, as well as individuals involved in other contact sports."

- Published24 October 2016

- Published12 April 2016

- Published31 May 2016

- Published19 March 2012