Challenges facing Scottish universities after Brexit

- Published

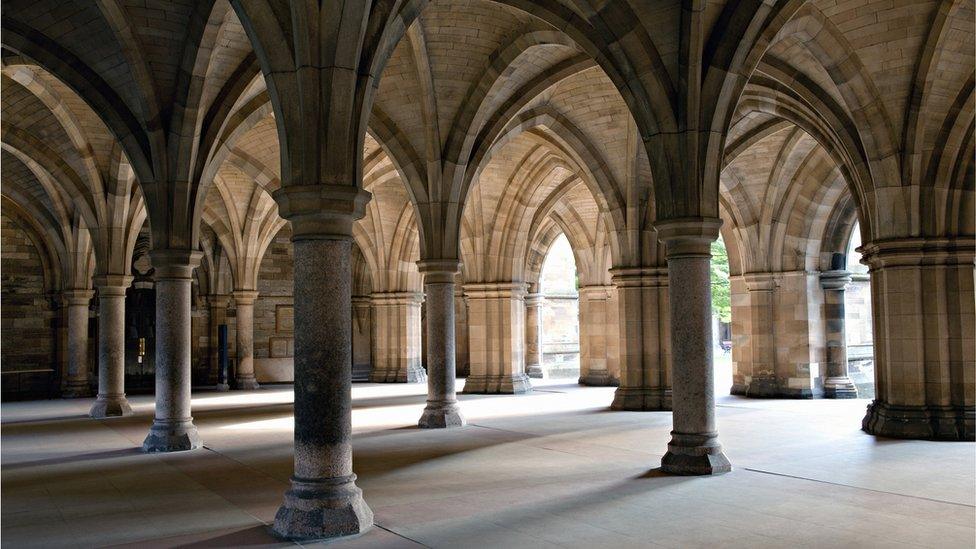

The Scottish Association for Marine Science carries out high-level research

In his second report on how Scotland's universities may be affected by the decision to leave the European Union, external, BBC Scotland education correspondent Jamie McIvor assesses the possible impact on postgraduate students, academics and research.

The West Highlands of Scotland suffered for generations from depopulation. Many of the brightest young people were lost to their communities when they left for university.

Oban is one of the busiest towns in the area. Over the summer, its population always swells with tourists from home and abroad.

But now its population is more diverse across the whole of the year.

The sign on the road explains why: Oban now calls itself a university town.

This is thanks to the University of the Highlands and Islands - a federation of colleges and institutions at locations from Shetland to Kintyre.

It offers opportunities to students from across the region but also brings in new blood from far and wide including postgraduate students from other EU countries.

Universities across Scotland argue that the EU is important to them: some 10% of research funding comes from the EU while about 16% of academic staff and more than a fifth of research-only staff are from other EU countries.

UHI argues the EU has been even more important to it than some other universities as European money has helped to develop the region's infrastructure and benefited the individual institutions within UHI.

One institution within UHI is the Scottish Association for Marine Science based just outside Oban.

Thanks to the influx of students, Oban now has a more diverse population than ever

It carries out high level-research and leads a prestigious masters course in aquaculture, environment and society - in collaboration with institutions in Crete and France - which attracts postgraduate students from across the European Union and beyond.

A senior lecturer at SAMS UHI, Dr Elizabeth Cottier-Cook, believes big challenges lie ahead to ensure this course and universities generally do not lose out after Brexit.

She said: "The collaborative links that I have forged over my research career - you cannot put a price on that - and I think it would be a real shame to lose those links."

Only two of the latest cohort of 25 students on the masters are from the UK. The remainder come from overseas, many from EU countries.

One of Dr Cottier-Cook's concerns touches on a widespread worry within academia. There is concern that it will be much more difficult for British universities to work jointly with universities in EU countries on academic research or could be cut off from EU-wide funding.

EU funding pots

Asked how damaging it would be for universities generally if such links were not maintained, her answer was stark: "Pretty terrible."

There is already anecdotal evidence to suggest teams at British universities may be encountering new challenges joining some international consortia.

Universities accept the result of the referendum but want to minimise the practical impact on them of leaving the EU.

Alastair Sim, of Universities Scotland, says one option would be for the British government after Brexit to choose to pay in to EU-wide funding pots.

He said: "We want to be part of these schemes on at least as close a basis as Norway is so that we're still part of that common European research endeavour with our closest neighbours."

Universities win funding for research from a number of sources including UK and Scottish funding bodies and the private sector. The cash lost if EU-wide funding were to stop could, in theory at least, be made up in absolute terms.

What some academics worry about more is the risk to British involvement in research carried out collaboratively by teams at different EU universities and that funding in particular fields could be very hard to replace.

Back at SAMS in Oban, Alejandro Espi from Alicante in Spain is working on his postgraduate course. He studied for his degree in Scotland and opted to stay here. As an EU citizen, he has the freedom to live or work in any EU country, so remaining in the UK was not an issue.

One of his big concerns is over what his own, long-term position will be after Britain leaves the EU: will he need a post-study work visa to remain in the UK?

A wider concern at universities is that Britain may simply be less attractive for academic and research staff from EU countries.

A major question, which cannot be answered just now, is what arrangements there will be to ensure they can remain in the UK after Brexit.

Access to public services

Alastair Sim said: "For existing staff, we cannot tell them what conditions there may be for them to remain in the UK - for instance what entitlements they may have for access to public services in the future."

It seems unthinkable that academic and research staff from the EU would not be welcome in Britain. Mainstream supporters of Brexit did not question whether people with these skills were wanted. The issue within academia is about the uncertainty ahead or the fear over what the new arrangements could be.

At one extreme, might freedom of movement effectively continue? Alternatively, would work permits be required? If so, would universities need to show that they were offering a job to someone from the EU because they could not find a British citizen to fill the post? This issue - which affects many other employers - will need to be discussed and settled in the coming negotiations.

At best, universities hope current relationships can be maintained.

At worst, they fear less money, less collaboration on groundbreaking research and fewer opportunities or even barriers for students, staff and academics.

- Published14 November 2016