His name was Henry Summers - but who was he?

- Published

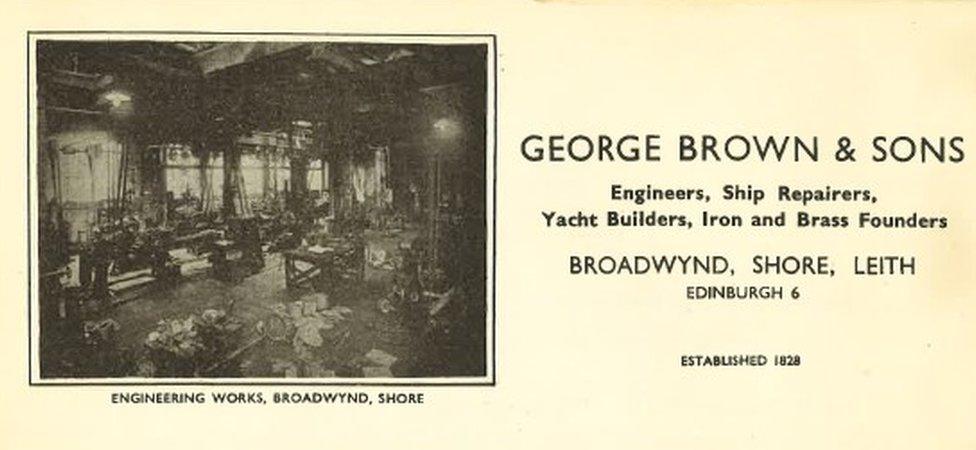

Harry (on the left) with workmates at George Brown & Sons

When I heard the story of an elderly man who had lain undiscovered in his flat for three years I wanted to know more about who he was.

It began with an urban horror story.

In June 2015 police in Edinburgh were called by a GP because an elderly patient named Henry Summers had not been seen for several years.

The police went to Henry's address in Leith, one of the most densely populated areas in Scotland.

Henry lived in a top-floor flat in Leith

They went to the door of his top-floor flat on Easter Road and knocked but got no answer.

The police called a locksmith but he couldn't open the door because the hinges had fused as it hadn't been opened for years.

When the police knocked the door down they found a mountain of mail in the hall and Henry Summers was inside, dead.

He had been dead for three years, undiscovered, because all of his bills were paid by direct debit.

Police beat down the door to gain entry to Henry's flat

The media were full of recrimination and finger pointing.

I used to work with old people and had seen this before. It's easy to de-personalise older people.

We talk about parents and pensioners as if they are conversation-starters about social issues.

But the way someone dies isn't a summary of their whole life.

Who was Henry Summers?

A year after his body was found, I wanted to find out who Henry Summers had been during his 80-something years of life.

My detective work was for a BBC Radio Scotland documentary and it began with the reports of the incident in the local papers.

Journalist John Connell had interviewed neighbours at the time the body was discovered.

Denise Mina started her investigations at the home where Henry was found

They told him they had last seen Mr Summers three years earlier in 2012.

They saw him being stretchered out of his house into an ambulance.

He was wearing an oxygen mask and looked very grey.

The neighbours didn't know that Henry had been discharged and returned to his home.

The nameplate on Henry's front door

Later, one of the neighbours knocked on the door. He opened Henry's letterbox and smelled what he assumed was food going bad.

They said Henry kept himself to himself but was very dapper, always wore a blue jacket and a flat cap and he used to whistle as he was coming up the stairs.

Then a twist: a man came forward and said that the man found dead in the flat in Easter Road could not possibly be Henry Summers.

Henry Summers of Easter Road was his father and had died and been cremated in 2012.

'Unfathomable coincidence'

My Henry was 10 years younger than the man's father.

This meant that two men with the exact same name had lived in the same street and died in the same year.

It sounds like an unfathomable coincidence - but it wasn't.

Later, once we knew who Henry was, it would make perfect sense.

Henry lived at 300 Easter Road in Leith

I went to Easter Road and asked in the local café, the pub, newsagents.

The police wouldn't release a photo of Henry so it was difficult to know if they were remembering our Henry.

Some people thought they'd seen him but he was variously reported as being in his 60s and his 90s.

Some said he stood at the bus stop every morning, caught the number 35 and then came back on it in the afternoon.

He bought milk and newspapers every day too but the shopkeepers had changed in the three years since he was last seen. He was a difficult man to find.

Funeral paid for

I had assumed that Henry had been forgotten and would have been buried by the city council.

Public health funerals often happen when a person has died alone and impoverished.

I was completely wrong.

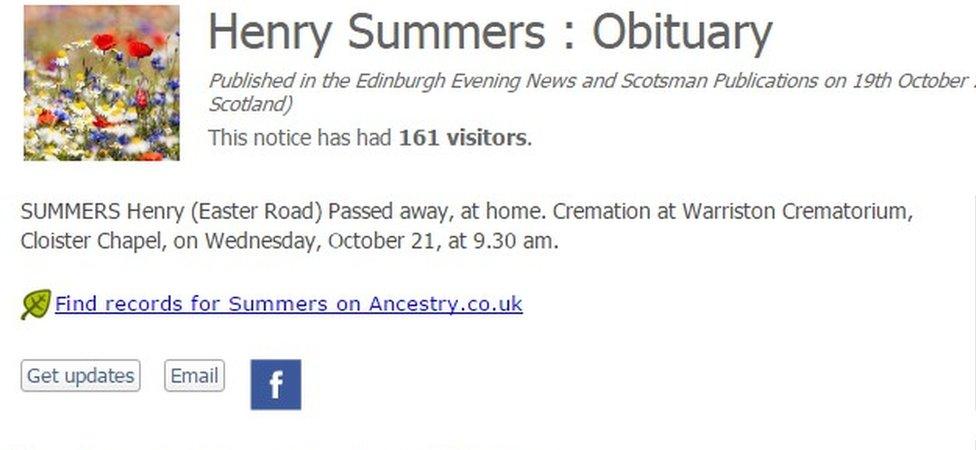

In fact, Henry's funeral had been organised and paid for and an obituary had been printed in the paper.

I wrote, via the crematorium, to the person who paid for the funeral but they wanted to remain anonymous.

I also assumed that Henry's flat was rented, perhaps the landlord would know him, but Henry owned his flat outright.

He had bought it in 1970 and paid his mortgage off completely in just four years.

It was £1,500. Where on earth did he get that money from? Was he from a rich family?

I was stuck so I went on BBC Radio Scotland's Kaye Adams programme to ask for information.

Left intestate

The documentary team were contacted on Facebook by people who thought they had seen a man matching his description in the Ocean Terminal Shopping Centre.

He was there regularly, reading the paper, quite content, they said.

The number 35 stops there so it seemed credible.

In the meantime, I tried to trace the person who inherited Henry's flat.

In Scotland, any property left intestate is dealt with by the National Ultimus Haeres Unit.

National Ultimus Haeres Unit

DEATHS REPORTED 01 JULY 2015

SUMMERS, Henry, d.o.b: 16/03/1929: place of birth: Leith, who resided at Flat 3F3, 300 Easter Road, Edinburgh , EH6 8JT and who died at Flat 3F3, 300 Easter Road, Edinburgh , EH6 8JT, on 24/06/2015. NUHU/113/15 - POSSIBLE RELATIVES TRACED

They list unclaimed property online so that any claims can be filed.

Henry's flat had been claimed but they couldn't tell us who the beneficiary was.

I contacted expert genealogist Dr Bruce Durie and using the Land Register and the census he solved the mystery of the two Henrys.

Our Henry was born in 1929 and had lived and worked in Leith all of his life.

He was an only child and lived with his parents, nursing his fragile mum until her death.

After that he moved from a flat in Thorntree Street just round the corner to the flat in Easter Road.

Henry was said to have taken the 35 bus from his home to Ocean Terminal in Leith

Here was the answer: Henry's dad, one of nine children, was brought up at several addresses in Couper Street, Leith.

This street was populated almost entirely by households by the name of Summers.

Most of those families, probably relations, had children named Henry.

The name 'Henry Summers' was as much a part of Leith as rope and drink.

Demographics changed

The only reason I didn't know that was that Leith has changed so much over the past 40 years.

It is gentrified now, the docks have shut, the demographics changed and the vast Summers family have mostly left.

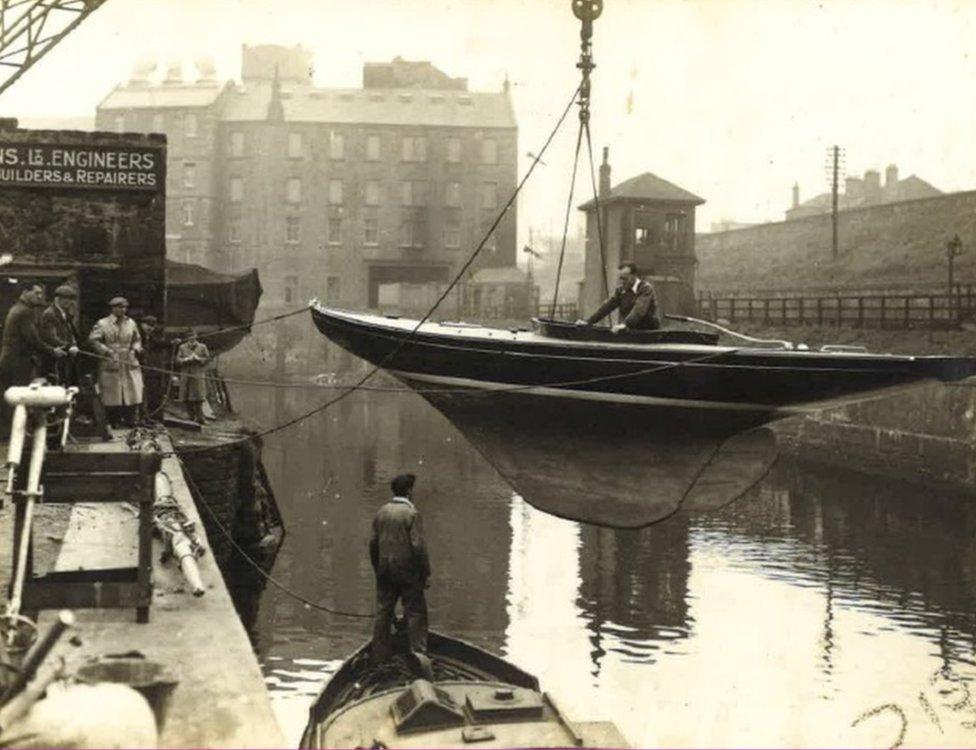

My Henry was a ships' carpenter, according to his death certificate.

This was an extremely skilled job with a long apprenticeship. Henry's family were labourers, so he had done well for himself.

They must have been very proud of him.

The mystery of the mortgage remained.

Maritime historian Dr Eric Graham speculated that Henry might have been a whaler or worked long haul.

Those ships would go around the world for months at a time and ships' carpenters could be paid a lump sum at the end of the voyage.

His name was Harry

It was all guesswork but then our original radio programme was broadcast and suddenly Henry came alive again.

His old pals heard it and contacted us, or the newspapers carrying stories about him.

He wasn't even known as Henry, everyone called him Harry.

Harry, it turned out, was a great laugh.

He was a Hibs fan, a brilliant carpenter and an angler.

His old gaffer told us Harry was plagued by a mysteriously intermittent case of lumbago, which only ever flared up when he couldn't be bothered doing a particular job.

His work pal, Andy, contacted us.

Harry (on the left) with workmates at George Brown & Sons

They worked together at George Brown's in Leith all the way through the 1970s.

Andy saw the obit in the paper and went to Harry's funeral.

He said Harry was a gent.

In the 1940s and 1950s, when Harry first started work, men in the high trades would wear a shirt and tie underneath their overalls. Harry still did this in the mid-90s.

Henry worked at George Brown and Sons in Leith

We heard that Harry was a good guy who didn't like sexist jokes, which was unusual in the docks in the 70s.

Another old work pal, Robert, remembered that Harry would pop in to see the guys after he retired to regale them with his latest adventures.

Harry was a confirmed bachelor, an only son and came across as bit of a mummy's boy, in a really nice way.

He was teetotaller when Robert knew him but their gaffer, Fred, told stories about Harry's wilder days when they would all laugh and Harry would laugh along with them.

Fred was a whaler and Robert never heard them speaking about whaling together, so he thought Harry probably hadn't done that. He didn't think he had ever been abroad.

Assistant manager at George Brown and Sons, Steve McIntosh, knew him well.

Harry had retired in the late 90s and loved river fishing for trout.

He was off every weekend to the Tweed and Dalkeith.

Harry didn't like drydocking the boats in winter or the rain, Steve said.

If Harry knew a boat was coming in and the weather was rotten, he'd call in sick with lumbago, an unusual condition for someone as active as Harry.

Very unusual in avid river fishermen.

Extraordinarily skilled

Steve said they wouldn't tell Harry the boat was coming in but Harry would have his revenge: if he knew they'd tricked him he'd call in sick the next day.

Despite this Harry was worth keeping on because he was so good at his job, extraordinarily skilled and meticulous.

It emerged that as well as the shipyard, he had been part of a team who "re-roped" the stage sets at the Churchill and Playhouse theatres in Edinburgh.

When Harry retired he used his bus pass to go anywhere - Galashiels, Berwick, Kirkcaldy.

The last time Robert saw Harry was in the St James shopping centre in Edinburgh city centre.

He was fit and active going for a bus. Robert asked him where he was going and Harry said he didn't know.

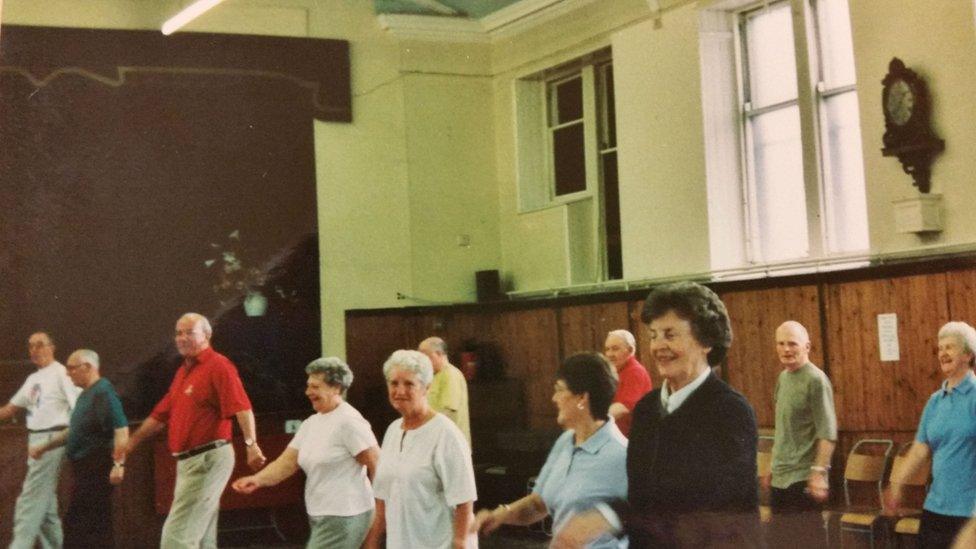

Harry in the back row of Rona's exercise class (wearing a red T-shirt)

He was going to jump on any bus and that would be his destination for the day.

Harry's physiotherapist got in touch.

Rona ran an exercise group for people with heart conditions and Harry always stood at the back with the other guys.

They all started at the same time.

The group would go for an annual day out at the Botanic Gardens and she also remembers Harry at their Christmas Ceilidh.

Henry (back left) on a trip to the Botanics with Rona's fitness club

When he stopped coming they were worried about him but Rona bumped into him and he explained he was having trouble with sore feet.

He never returned to the class but was spotted out and about, on the bus and at the bookies.

At the physio class Harry and another man would swap stories about the bookies, how lucky or unlucky they had been.

The mystery of the mortgage remained until we heard this. Harry was a gambler.

Maybe Harry just got lucky.

His Name was Henry will be broadcast on BBC Radio Scotland at 13:30 on Wednesday and will be available on the iplayer.

- Published26 June 2015