From hand-warmer to house-warmer for tech firm

- Published

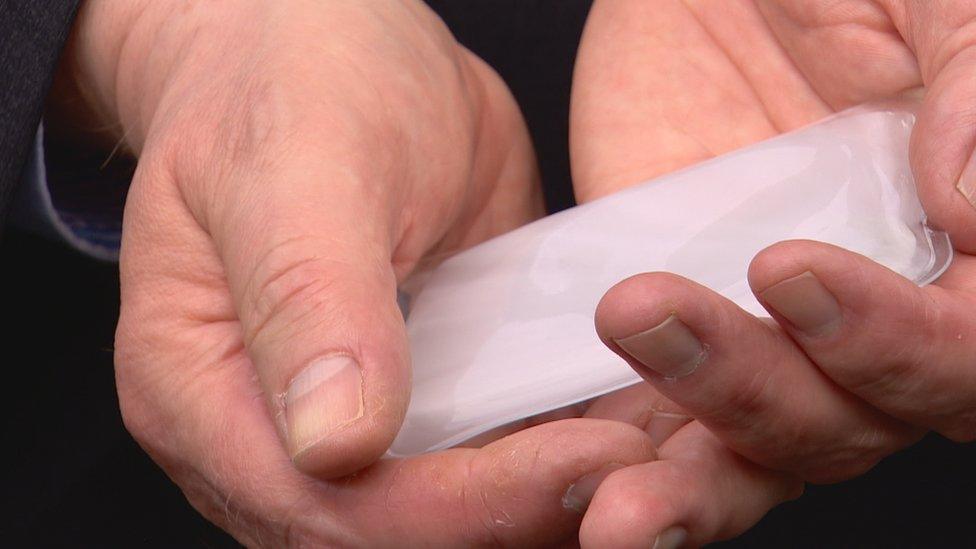

The house warmer uses the same "phase change" principle seen in handwarming gel

A tech firm has taken the principle behind hand-warmers and turned them into big batteries that can heat a house using solar power.

It is not really the weather for it but you might have one of these in a drawer somewhere.

A hand-warmer. A small plastic pouch filled with a gel.

Click the little piece of metal inside and you set off a chemical reaction.

The gel begins to turn into a waxy solid. As it does it gives off heat.

Phase change material

You can reverse the process by immersing the hand-warmer in hot water. The energy you are adding turns it back into a gel, ready to go again.

There's a name for the stuff in the pouch: a phase change material.

It's a bit like water when it freezes and changes from liquid to solid ice.

Except that gel is "freezing" at more than twice the temperature of boiling water.

So you get toasty hands (or feet - one of my colleagues has been known to stuff them into her socks when camping) and a wee bit of science theatre.

Sunamp has developed the cells containing a heat exchanger and the phase change gel

It took a creative leap to take the idea further: could you scale up the phase change process so a hand-warmer became a house-warmer?

Several big corporations - over several decades - tried to make it happen but each time the research petered out.

Now an East Lothian company with fewer than 30 employees has succeeded.

The equipment Sunamp have developed at their base in Macmerry has already been installed in 650 Scottish homes, providing heat and hot water for about half the cost of gas.

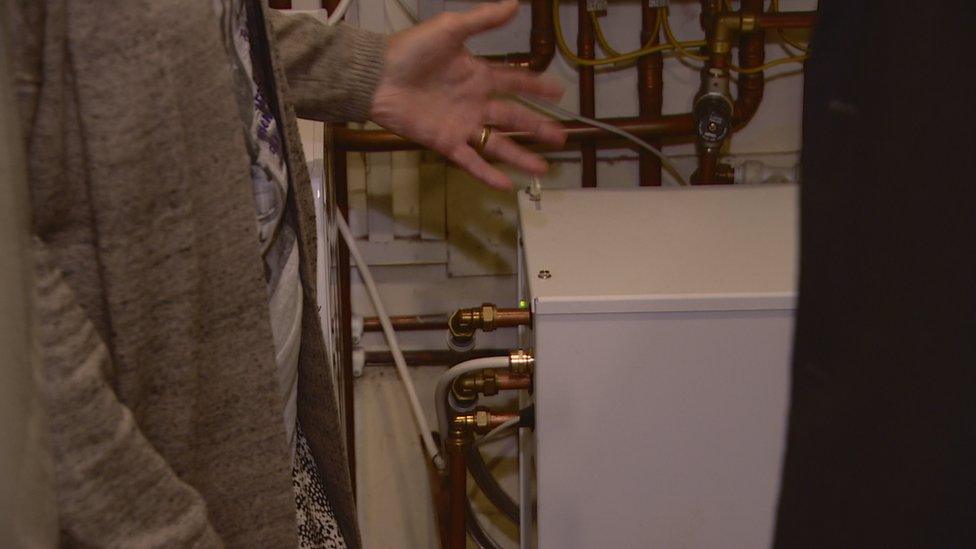

Joan Maclean's house is one of 650 to have the heat exchanger installed

Joan and Alexander Maclean's house is just a few miles from Macmerry.

The solar panels on the roof are a clue to how cosy it is inside.

The secret lies in a discreet white metal box in the airing cupboard. A box that Joan says "makes a lovely difference".

Joan says the box in her airing cupboard "makes a lovely difference"

She says: "It saves a lot of money, put it that way. You're getting your hot water for free.

"Before that, this house was a really cold, cold house."

With copper pipes coming and going from it, the box could be mistaken for a gas boiler.

But it's more sophisticated than that. It's a battery that stores heat instead of electricity.

Inside the white casing is a heat exchanger in a phase change material

At the heart of it a heat exchanger is immersed in a phase change material.

Like a handwarmer, the material melts when heat is put in from the solar panels.

Then when you turn on the tap in the kitchen or bathroom cold water flows into the heat exchanger, prompting the gel to solidify. Hot water flows out instantly.

It does it again and again. Each box is capable of thousands of cycles.

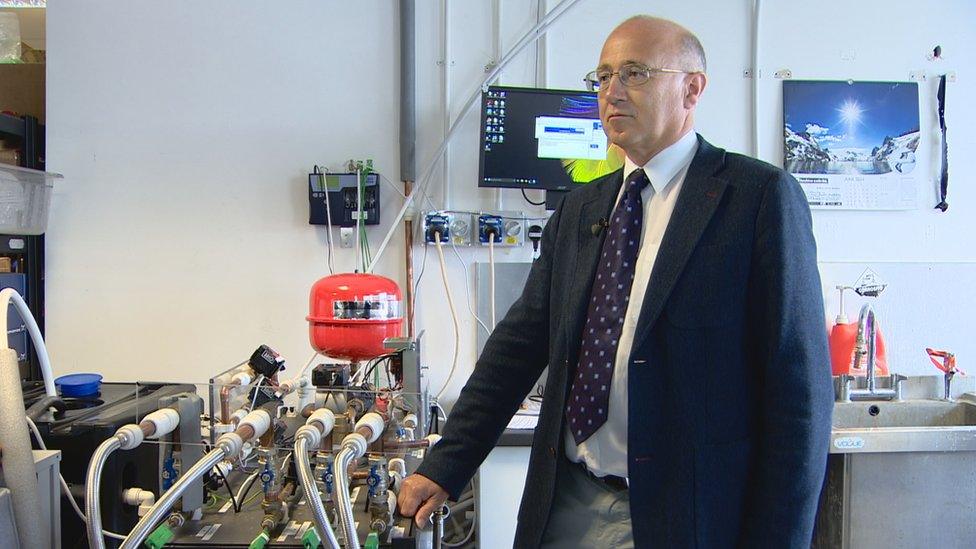

Sunamp's founder Andrew Bissell has been working on the method for eight years

It is the result of eight years of work by Sunamp's CEO Andrew Bissell. The former Edinburgh University academic wanted a better way of storing renewable energy until it was needed.

"It occurred to me that if you actually look at the pie chart of energy usage, far more of it is heat than electricity," he says.

"And yet far more of the effort goes into electricity compared with heat.

"So I said, 'I want to make a heat battery'."

The red cells can be stacked together inside units like the one in Joan Maclean's cupboard

There is a heat battery on the table in front of us. A red plastic cell containing the heat exchanger and the gel. (They also do blue cells - cold batteries.)

The red cells can be stacked together inside units like the one in Joan Maclean's cupboard. Other units are the size of small fridges, some even bigger than that.

Sunamp have a particularly imposing black one that rises from floor to ceiling of their kitchen and is reminiscent of the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Sunamp has an imposing black model in its kitchen

The principle may seem straightforward enough but there's been more to it than filling plastic boxes with gallons of handwarmer gel.

Sunamp had to find just the right formulation to ensure maximum heat transfer and battery life.

A huge number of possible formulations were screened using the Diamond Light Source - the UK's massive synchrotron in Oxfordshire.

It is not the sort of thing the average small to medium business could afford but Sunamp had entered into a partnership with Edinburgh University.

Prof Colin Pulham, from Edinburgh University, says his coleagues benefited from its partnership

The company got the science and the head of the university's school of chemistry Prof Colin Pulham says he and his colleagues benefited in return.

He says: "The governments are very keen that basic research leads to socioeconomic impact.

"This is a classic example of where something has been taken from the bench all the way into a product and has the potential to have a major impact economically, but also improving people's quality of life - and also of course reducing CO2 emissions."

Sunamp has linked up with university researchers

The matchmaker between Sunamp and the university was a publicly funded organisation called Interface.

In its 12 years of operation it has introduced well over 2,500 Scottish businesses to academic partners.

Dr Siobhan Jordan is director of Interface, which links business and academic partners

"We've worked with a range of companies," says its director Dr Siobhan Jordan.

"From food and drink companies that want to use hyperspectral imaging, a fantastic technology developed for the defence sector, to enable them to see inside cakes.

"We've worked with chocolate producers in looking at how the chocolate has flavinoids that are really healthy.

"But we've also worked with crofters, with farmers, with other energy companies - a whole range of different ideas."

Sunamp's heat batteries have given them a shot at success. Growing demand has attracted investors and the company is looking for bigger premises.

There's another success story. Sunamp's third employee came to Macmerry from Edinburgh university.

David Oliver was a postgraduate student but he is now the company's materials scientist

Then David Oliver was a postgraduate student. Now he's the company's materials scientist - and Dr Oliver, having completed his PhD on phase change materials.

He helped arrive at the final formula for the gel/solid in the heat batteries. The correct chemical description, he explains, is an alkali-soluble polymer.

He says: "A lot of people think of polymers as being plastics, hard materials.

"But some polymers also exist in a solution.

"So you can dissolve these plastics in other materials and you get some quite dramatic changes in properties."

Sunamp's formula contains several tweaks and additives.

But it's not too far removed from the stuff used to flavour some brands of salt and vinegar crisps.

We do not advise you to crack open a heat battery and having a taste.

No, definitely don't try that at home.