Passchendaele: The death of Jimmy Morgan and his mouth organ

- Published

A stretcher-bearing party carrying a wounded soldier through the mud during the battle of Passchendaele

War poet Siegfried Sassoon called Passchendaele "hell". The battle is remembered as one of the most horrific conflicts of World War One, in which hundreds of thousands died in the stinking mud of Flanders.

Relatives of two Scottish soldiers have traced the stories of men involved in the battle and will be at the Menin Gate Memorial on Sunday to mark the centenary.

Sara McCann's great-grandfather L/Cpl William George Brough was killed on the first day of Passchendaele, officially known as the Third Battle of Ypres, on 31 July 1917.

Her research led to the discovery that the Black Watch soldier, from Dundee, was known to the lads at the front as "Jimmy Morgan", a nickname earned through playing the mouth organ in the trenches.

Willie Brough was said to be the original Jimmy Morgan in the popular poem

The Battle of Passchendaele lasted three months and cost hundreds of thousands of lives

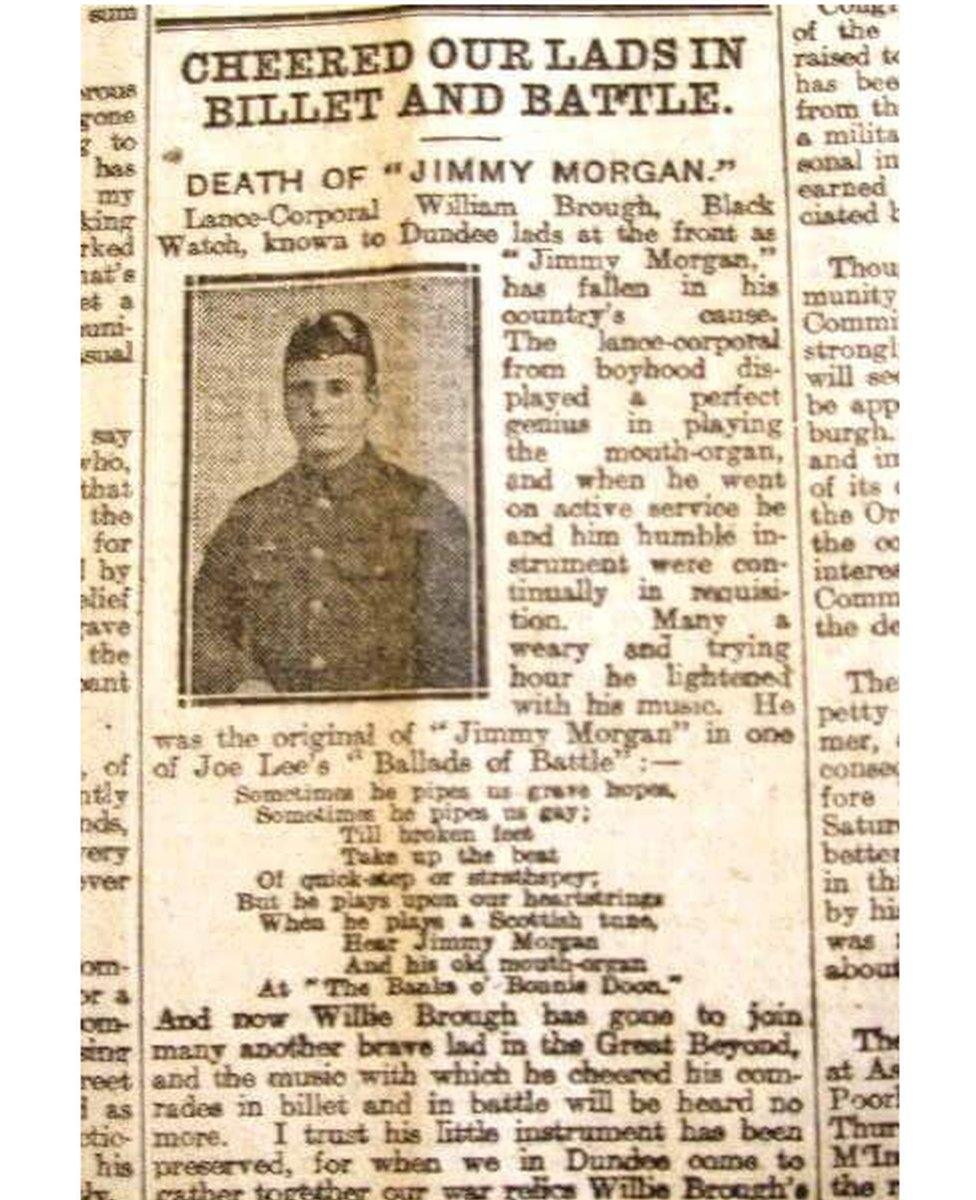

A newspaper report on the death of Willie Brough tells how his mouth organ tunes were immortalised in a poem by popular Dundee soldier-poet Joseph Lee.

The poet changed the name of the man behind the mouth organ to Jimmy Morgan to help his verse rhyme but always acknowledged that the best player in the battalion was Willie Brough.

The newspaper account says the Black Watch soldier had displayed a "perfect genius" for the mouth organ since boyhood and that he "cheered his comrades in billet and in battle".

It says he lightened "many a weary and trying hour" with his music, especially Scottish tunes, reminding the troops of home.

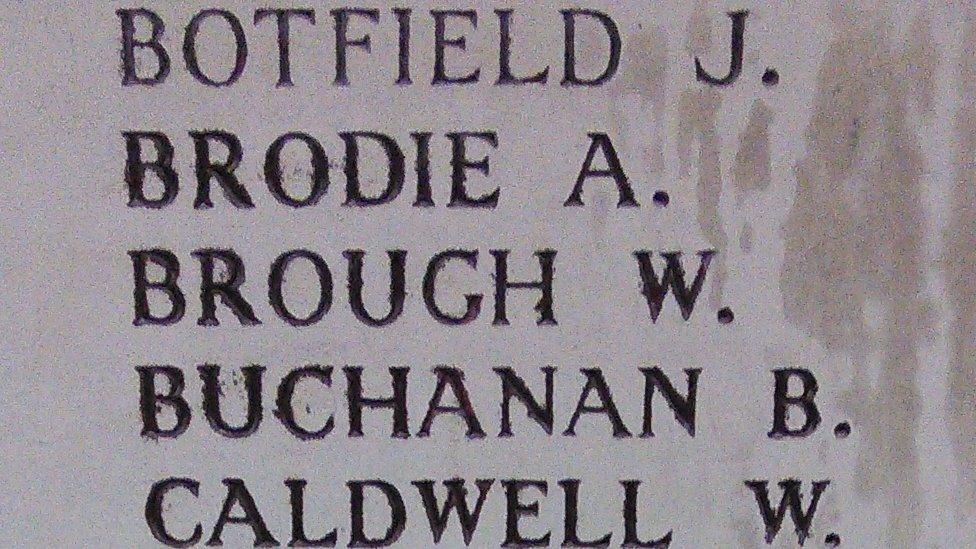

Willie Brough's name on the Menin Gate Memorial in Belgium

Sara McCann told BBC Scotland she was "incredibly proud" of her great-grandfather.

She said: "From what I know of the battle it was hideous. People were drowning in the mud because of the rain. It was just the most awful time.

"He was killed on the very first day of Passchendaele and in one way I'm glad he was killed at the start."

She says the story of his mouth organ playing "brought him to life" for her and other relatives because it told them about his personality.

Sara says: "What I love most about him is that even in those circumstances, which were hideous, he was able to keep his spirits up and lift others as well.

Passchendaele

"He had a positive effect and lifted morale.

"Music must have been one of the few pleasures they had to take their mind off it and remind them of home."

Brough, who was married with four children, had joined the Army in 1914 and seen two years of service in France before Passchendaele, including Arras and the Somme.

The newspaper account of Willie Brough's death ends with the hope that his fabled mouth organ would be placed among Dundee's war relics.

Unfortunately, in the mud and chaos of the battle 90,000 bodies were never identified.

Neither Brough nor his mouth organ were recovered.

Sara's research has located where the trenches of the 9th battalion were and she visited the field three years ago.

She now plans to go back to Belgium for the 100th anniversary and place a mouth organ at the Black Watch corner at Menin Gate.

Newspaper tribute on the death of "Jimmy Morgan"

It reads: "Lance-corporal William Brough, Black Watch, known to Dundee lads at the front as "Jimmy Morgan", has fallen in his country's cause. The lance-corporal from boyhood displayed a perfect genius in playing the mouth organ and when he went on active service he and his humble instrument were continually in requisition. Many a weary and trying hour he lightened with his music. He was the original "Jimmy Morgan" in Joe Lee's "Ballads of Battle".

Sometimes he pipes us grave hopes/Sometimes he pipes us gay/Till broken feet/take up the beat/of quick step or strathspey

But he plays upon our heart strings/when he plays a Scottish tune/Hear Jimmy Morgan/and his old mouth organ/ At "The Banks o' Bonnie Doon"

And now Willie Brough has gone to join many another brave lad in the Great Beyond and his music with which he cheered his comrades in billet and in battle will be heard no more. I trust his little instrument has been preserved, for when we in Dundee come to gather together our war relics Willie Brough's mouth organ should certainly have a place among them."

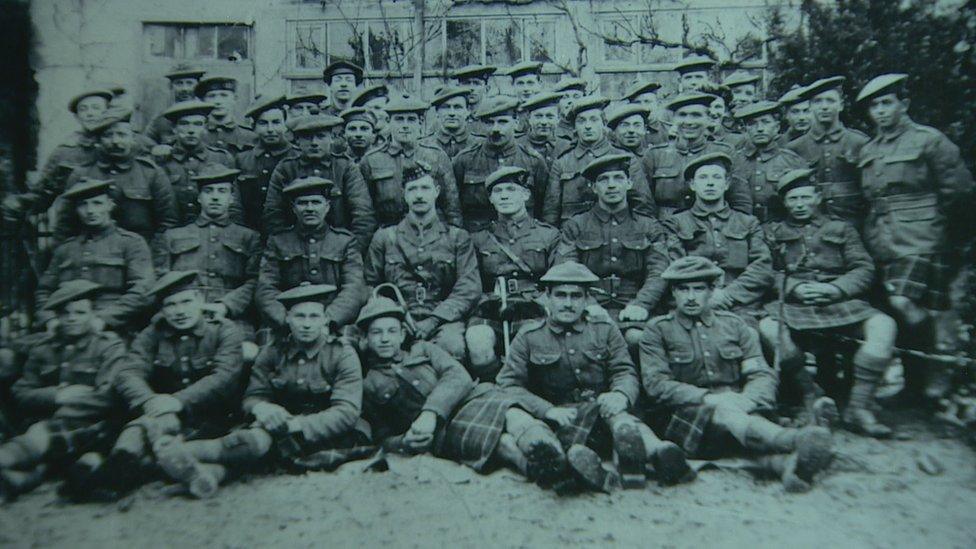

John McDonald (centre) with a group of soldiers in France during WW1

Passchendaele, like the Somme, has come to symbolise the horrors of World War One.

The Allied assault was launched in the early hours of 31 July 1917.

Torrential rain meant that the British and Canadian troops were fighting not only the Germans but a quagmire of stinking mud that swallowed up men, horses and tanks.

The brutal trench warfare lasted three months before the Allies recaptured the village of Passchendaele.

About a third of a million British and Allied soldiers had been killed or wounded in some of the most horrific trench warfare of the conflict.

William McDonald's grandfather, John Alexander McDonald, fought in the conflict.

He was a 20-year-old grocer from Elgin at the beginning of the war, married with a young son.

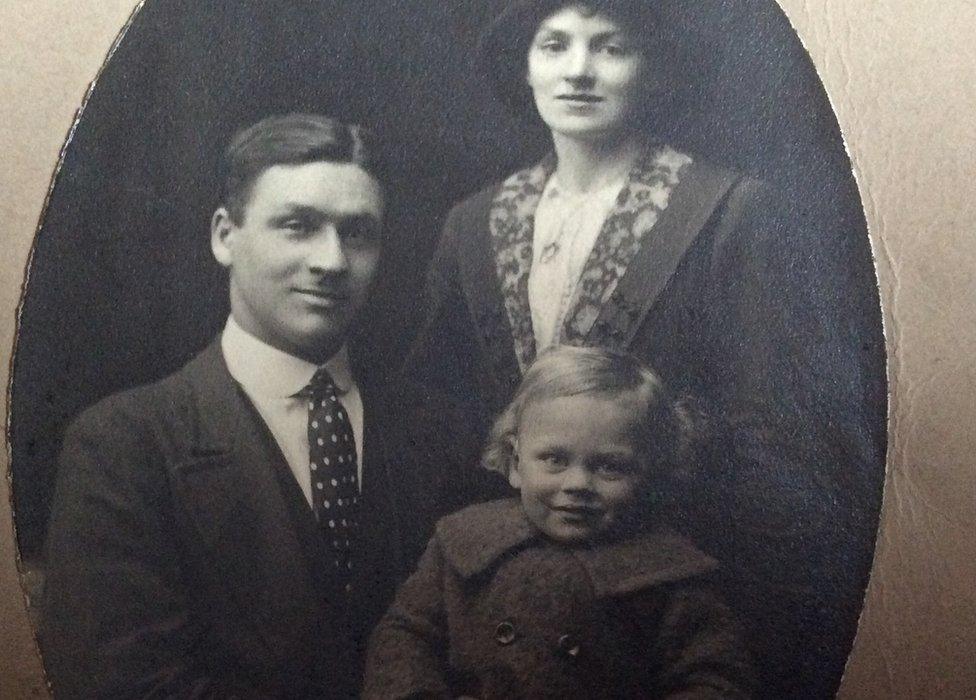

John McDonald with his wife, Isabella, and his son John, who would be William McDonald's father

At the outbreak of WW1, he joined the the 6th battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders, which drew men from the Moray area.

After training in Bedford, he went to France in May 1915 and saw two years of action in battles such as Arras and the Somme before moving to take part in Passchendaele.

His grandson told BBC Scotland: "On the day of the battle they were the second wave of attack. They were heading for a stream which was the target to get over for that day.

"It was seemingly freak weather conditions. A lot of rain came on. The artillery had blown up all the drainage so the place was a sea of mud.

"They advanced and the conditions became muddier and muddier. It was a grim time for them all. They were cheerful despite it all and very courageous."

William McDonald's grandfather and great uncle served in the same battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders

Mr McDonald adds: "It must have been quite a scene to see them wearing kilts and charging through, trying to make their objectives."

His grandfather won the Military Medal for his actions on the first day of battle but the circumstances of his bravery are not recorded.

The Seaforth Highlander survived three months of the battle at Passchendaele but was killed in another battle in March 1918.

Mr McDonald said he had some letters written by John McDonald which gave an insight into his personality.

"I think he was a smart chap," he says.

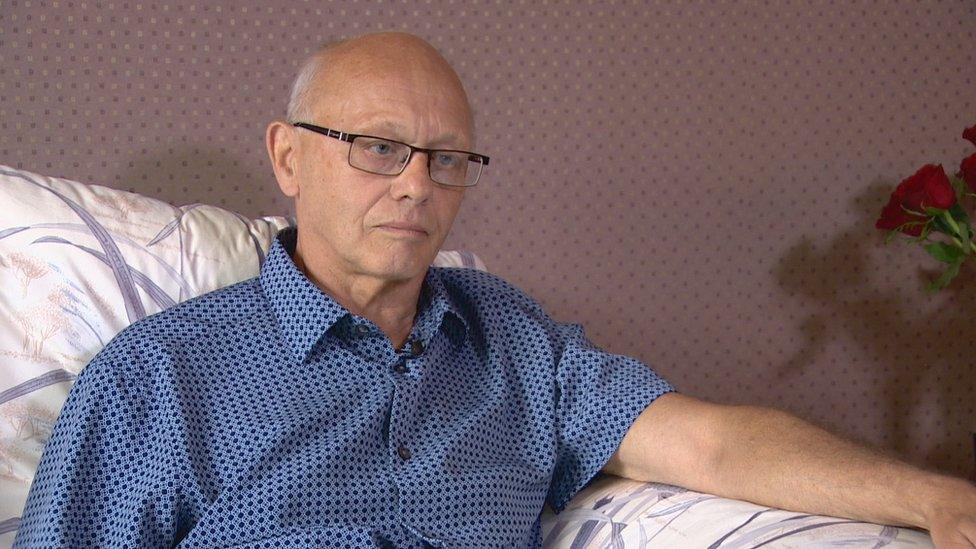

William McDonald says his grandfather survived Passchendaele but died in a later conflict

"A keen family man. He missed his son and wife. It was difficult times for them. He talks about missing Elgin and being keen to get home."

"My dad must have been about two when his father went to war. He only saw him three or four times before he died."