High-speed rail tested in university lab

- Published

GRAFT II is a fatigue testing facility for high-speed railways

High-speed rail is up and running in Scotland. Not the trains, mind, just the rail.

In a laboratory at Heriot-Watt university, researchers are pounding a stretch of German high-speed track using a machine that can create a year's worth of traffic in a single day.

It's the first time such testing has been carried out in the UK.

Three hundred and sixty kilometres per hour (224 mph) is a respectable speed for a high-speed train, and PhD students Ahmet Esen and Zelong Yu are at the controls.

The short sections of rail are clipped into a continuous concrete slab

Not of a train but of GRAFT II.

GRAFT being the acronym of "geopavement and railway accelerated fatigue testing".

With a gantry built of huge yellow and red girders it looks a little like a spinoff from the offshore oil industry.

In fact it's a fatigue testing facility for the experimental and numerical analysis of high-speed railways.

It was installed four years ago.

But now it's conducting new tests which are almost literally ground-breaking.

The sections of rail are put under pressure from pistons

Beneath its mighty pistons, each capable of delivering 20 tonnes, lies a short length of slab track.

Instead of sleepers, the rails are clipped to a continuous concrete slab. It's the type of track on which Germany's high-speed trains run.

But will it work on UK soil?

GRAFT II is operated at Heriot-Watt University

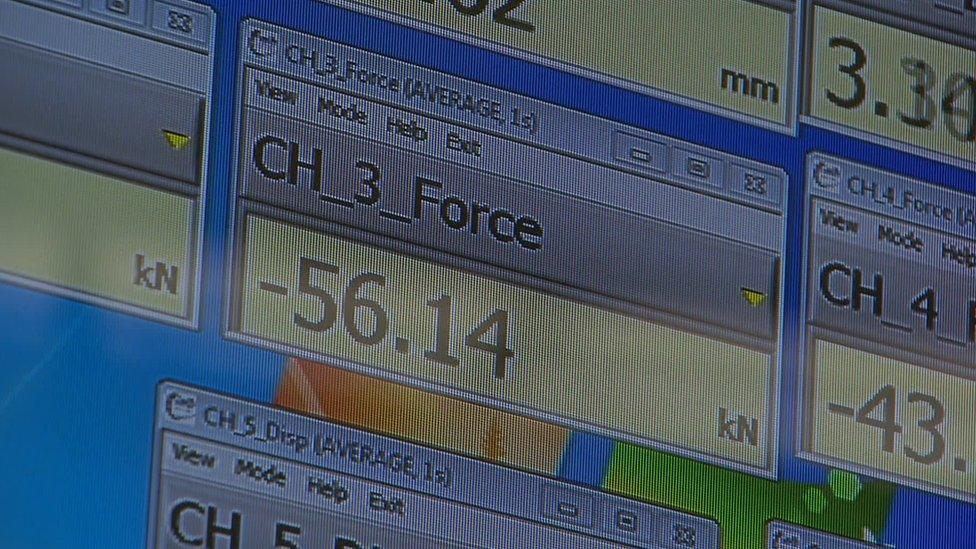

At the control screens, Ahmet is trying to find out.

He says: "We are applying high-speed railway loading with different load combinations - like passenger carriages, passenger locomotives, freight train loads - at different frequencies, which means different train speeds."

Sensors measures the dynamic stresses on the rail

A stretch of high-speed track in the UK could have to withstand a pummelling of 20 million tonnes of axle load every year.

This rig can deliver that in 24 hours. In a few weeks of testing, a lifetime of wear and tear.

The German experience shows slab track works there.

The GRAFT II can deliver a lifetime of wear and tear in a week

But this testing programme is equally concerned with what lies beneath - the ballast, aggregate and soil below the slab.

Because if different parts of these sub-layers settle at different rates it could lead to a bumpy ride and worse.

A train travelling at high-speed creates an effect known as a Rayleigh wave. It travels through the soil sending forces forward, up, back and down.

It sounds like bad news and potentially it is. Rayleigh waves are what destroy buildings in an earthquake.

It's a lot like a sonic boom but instead of aircraft and air, think of a train and the soil beneath it.

Prof Omar Laghrouche is director of Heriot-Watt's Institute for Infrastructure and Environment

The director of Heriot-Watt's Institute for Infrastructure and Environment is Professor Omar Laghrouche.

He says: "Recent research has shown that for high-speed railways, unlike for conventional speeds, there are different phenomena taking place.

"It's similar to the case of supersonic flight.

"So as the flight increases speed catches up with the sound speed it leads to a sonic boom.

"There's an exactly similar phenomenon happening in solids."

The slab track provides increased stiffness but the researchers want to find the optimum materials to put underneath it.

It took several months to build the sub-layers which lie beneath the track. Longer, in fact, than it's taking to run the tests.

The 56 tonnes of material has come from the construction company Tarmac in a joint venture with the slab track builders FFB Max Bögl.

The research, which also involves the University of Leeds, is being funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

It's part of a project called Lowering the Costs of Railways using Preformed Systems.

The EPSRC aims to improve track behaviour and reduce the cost of new high-speed railway lines.

There's more to this track testing than building your own railway and pounding it.

On the track and in its bed have been placed a sophisticated array of sensors, 32 in all.

Dr Tina Marolt says the positions of the sensors have been chosen very carefully

The research associate on the project, Dr Tina Marolt, says they measure dynamic stresses.

"The positions of the sensors have been chosen very carefully," she says.

"And the results we are getting right now from the testing are very promising."

The research will feed into the preparations for - and no doubt the debate over - the High Speed 2 line from London to Birmingham and beyond.

The right kind of layers beneath its track will one day give passengers a smooth ride and - all going well - restrict damage to nearby structures.

That remains some time in the future.

In the meantime, this small stretch of track is likely to be the closest Scotland gets to high-speed rail for many years to come.