How silver became Scotland's precious metal of choice

- Published

A selection of Scotland's earliest silver from about 80-100AD

Silver - not gold - was the most powerful material in the formative history of Scotland in the first millennium AD, yet none was mined here. How did silver become Scotland's precious metal of choice?

Scotland's earliest silver arrived via the Roman army, in the form of coins. This was the pay packet as far as the Roman soldiers were concerned.

Local tribes, who received gifts of silver coins, were less interested in the currency value - they couldn't spend them outside the Roman Empire.

But to them this new material was a symbol of status and Roman favour.

Hacksilver

By the late 3rd Century AD, we see a new phenomenon - 'hacksilver'.

Research undertaken for the National Museum of Scotland's new exhibition - Scotland's Early Silver -, external and some of the new finds we'll be showing, have led to significant changes in our understanding of the practice.

As the name suggests, we're talking about silver which has been hacked up - vessels, tableware and other objects.

Part of a flat silver plate showing Venus rising from the waves, from Traprain Law (410 - 425 AD)

Previous finds, such as the spectacular hoard unearthed in 1919 at Traprain Law in East Lothian, were originally taken as showing that this was something that 'barbarians' did to their 'loot'.

But, in fact, the initial hacking of silver was done within the Roman Empire.

Silver objects were turned into bullion - fragments carefully cut to standard Roman weight measures and then often folded into handy packages.

Hacksilver was used by the Romans in what we might now understand as a form of frontier diplomacy, whether gifts or bribes to quell a troublesome tribe or even set them against their neighbour.

Alice Blackwell inspects the Dairsie Hoard with finder David Hall

This went on for far longer than we had previously thought.

Earlier this year, BBC Scotland reported the discovery of a silver hoard from Dairsie in Fife, found by teenage metal detectorist David Hall.

The hoard was of hacksilver and dates to the late 3rd century AD, making it the earliest found beyond the Roman frontier anywhere in Europe.

It showed that the use of hacksilver had begun a century earlier than previously thought.

Archaeologists think the silver came to Fife as a gift or payment

The Dairsie silver is going on display at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh

Since David's discovery, we've been engaged in a very complicated jigsaw puzzle.

Not only had this particular silver been hacked up by the Romans, it had then been further damaged by the plough over many years - so we've had more than 400 tiny fragments to piece together, first restoring their hacked-up state and then working out what the original objects looked like.

The results of these many painstaking hours of this work will go on show in the exhibition as the Dairsie hoard goes on public display for the first time.

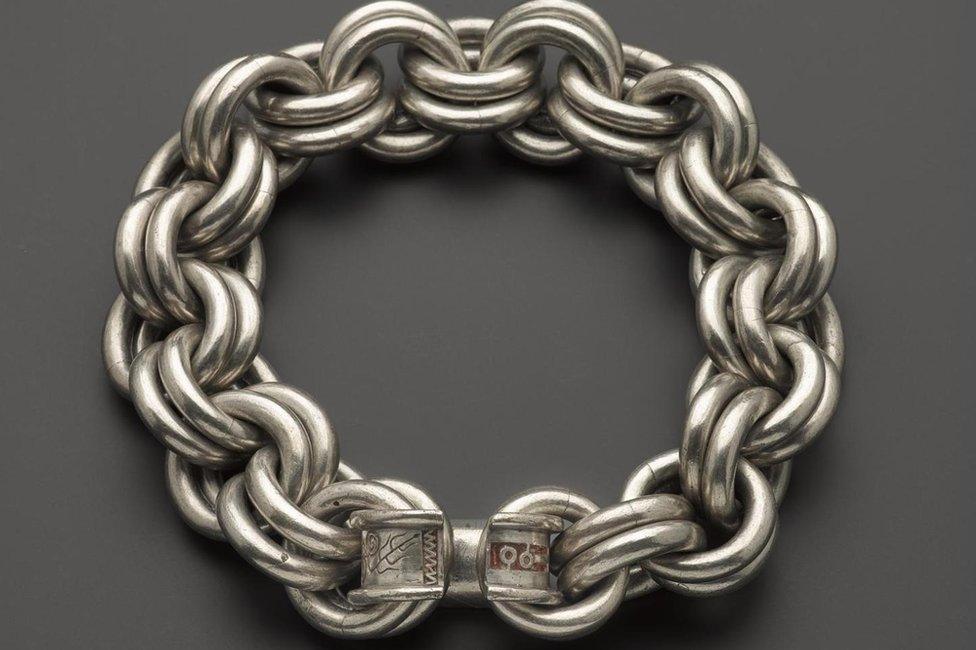

Pictish chain of 22 double links with a pennanular terminal ring, from Whitecleugh, Lanarkshire, (6th or 7th century)

This hacksilver represents a change in policy, and one which had an important legacy in Scotland.

Unlike coins, hacksilver was designed to be reused and remade.

For the first time we see evidence of silver-working in Scotland - crucibles with tell-tale traces of silver.

Pictish chain of 22 double links with ring engraved with designs inlaid with red enamel, from Whitecleugh, Lanarkshire (6th or 7th century)

These were used to make fine, subtle items of jewellery such as pins and finger rings, but also massive neck chains.

Eleven of these spectacular adornments have been found, from Lanarkshire to Inverness-shire.

They date to around the middle of the first millennium, all made from that recycled Roman silver.

They are classic 'status' jewellery, made to impress, to show the power and wealth of the owner.

In that sense, they are timeless, actually quite strikingly contemporary in their appearance for objects made over 1,500 years ago.

The largest weighs about 3kg - nearly twice as heavy as the Crown of Scotland made about 1,000 years later.

It's probably too much of a leap to make that a direct comparison, but this period does see the gradual formation and emergence of more organised power structures underpinning what will eventually become the kingdom of Scotland.

With the collapse of the western Roman Empire, diplomatic gifts of silver dried up, so the existing Roman silver had to be carefully managed.

Once again, hacksilver was the answer, with objects cut up and fragments carefully preserved for reuse.

In the post-Roman period, silver retained its importance and value.

Another hoard going on show for the first time, from Gaulcross in Aberdeenshire, tells us that this hacking practice continued after the collapse of Roman government in Britain after AD 400.

Another hoard going on show for the first time is from Gaulcross in Aberdeenshire

This was the result of revisiting a site where a discovery had previously been made in the 1830s.

Only three objects survive from the initial find, all intact pieces of jewellery.

It was unfortunately fairly common in the Victorian era for finds of precious metal to be melted down and reused.

In one sense, that's just a continuation of what had always been done with it, but it does rather hamper our efforts as archaeologists.

To make matters worse, the original finders had dynamited the location to level it off for farming, removing two stone circles.

Even so, it was felt that there must be more material remaining at the site, and a fresh excavation yielded many more fragments of silver, hacked rather than complete.

Bowl of silver, decorated with four pairs of grotesque animals, interlocking, Pictish, from St Ninian's Isle, (8th century)

Those long-recycled Roman silver supplies start to run low in the second half of the millennium.

We can see this from the greenish tinge of some later silver objects, indicating that people have started cutting their silver with copper alloys to make it go further.

Penannular silver brooch with thistle terminals, the balls undecorated, with a series of mouldings on either side, from Skaill

This changed with the coming of the Vikings, and the linking of Scotland into wider trade networks.

This brought new supplies of silver and new ways of using it, in new forms of powerful jewellery.

Group shot of silver arm rings from the Burray hoard (997 - 1010 AD)

It is unusual for an exhibition to encompass such a large span of time and to focus on one material.

Both choices reflect a new research direction to cast light on an old problem - the emergence of kingdoms in what became Scotland.

The centuries after Rome have few historical sources which are much chewed over - but archaeological evidence can provide fresh perspectives.

Our long-term view allows us to see how the use of this key power material changed as societies developed, and power centres rose and fell.

In this silver lies a tale of early kingdoms drawing on Rome's legacy to show power and prestige.

It sheds fresh light on this obscure but critical period.

Alice Blackwell is the Glenmorangie Research Fellow at National Museums Scotland and curator of the new exhibition.

- Published5 February 2013

- Published1 August 2017