Thawing the past to forecast the future

- Published

- comments

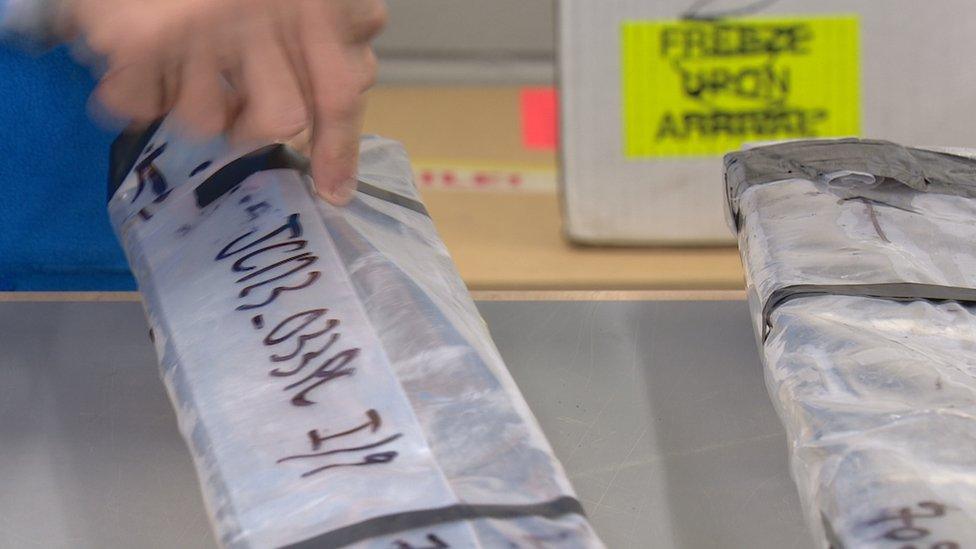

Cores taken from the seabed just after extraction on Britice-Chrono

How did Scotland's last Ice Age end - and why does it matter now?

A big research programme has been trying to answer both questions by X-raying samples from beneath Scotland's seabed and beyond.

The project is called Britice-Chrono.

It involves researchers from institutions across the British Isles with funding from the UK's Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).

The project has involved three years of offshore and onshore sampling and two more studying what they found.

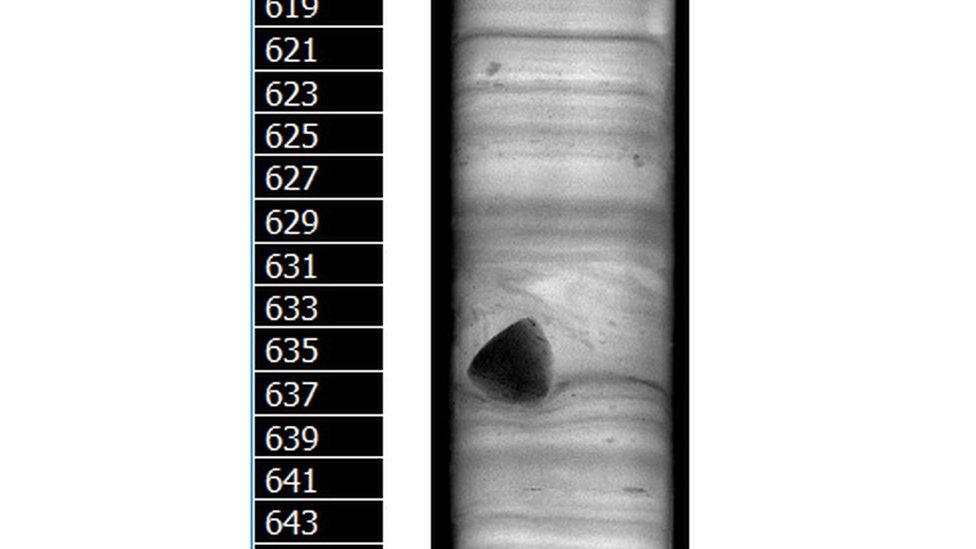

An X-ray of Core 033 with scale and dropstone which has fallen from an iceberg

The first results are being published and they are telling us more than ever before about how glaciers melted between 30,000 and 16,000 years ago.

Much of the work was carried out by NERC's Royal Research Vessel James Cook.

Two cruises took it around the British Isles, gathering tonnes of seabed samples from places as far apart as Foula and the Isles of Scilly.

These were far from being pleasure cruises. The scientists worked an arduous shift pattern: 12 hours on, 12 off, for weeks on end.

The team prepare to lower the Vibrocorer into the sea at night

More than 900 samples were lifted to the surface, most of them acquired using a device called a Vibrocorer.

At the British Geological Survey's Lyell Centre near Edinburgh - happily, on dry land - they show me how one works.

It's big and orange and looks like a drilling rig. But to drill down would be to destroy the samples you are looking for.

The Vibrocorer goes into the sea from the RRV James Cook

Instead there's a one tonne module at the top containing two weighted cams.

As these move they create the vibration which sends the sample tube through the seabed and on down.

Davie Baxter is at the controls. He explains what happens when the core is brought to the surface.

He says: "As soon as it is landed the scientific party are desperate to get the core sample.

"It is sealed, capped, marked up - and then the scientists disappear into their magic laboratories."

Core samples were taken and returned to the lab

The scientists use, if not actual magic, then certainly an impressive array of technology.

Dr Tom Bradwell, a lecturer at Stirling University, who led the sampling around the Scottish coast, reels off the tools they deployed.

"Multi-beam imagery of the sea floor, we've also used seismic imagery that sees below the sea floor," he says.

"And then another dimension. We've got to date those sediments. So when we've recovered the sediments we want to know how old they are."

That involves both radiocarbon and cosmogenic dating.

The latter involves calculating when a sample was last exposed to sunlight. This, remember, on samples that can be 30,000 years old.

For now the cores lie in a cold store at the Lyell Centre.

Dr Tom Bradwell led the sampling around the Scottish coast

Dr Bradwell lays one out.

It's split lengthwise and reveals what seem at first glance to be some fairly unprepossessing lengths of grey-brown mud.

X-rays and CT scans can reveal details we can't see, micro-fine layers of mud, silt and sand that have settled out of meltwater from the front of an enormous glacier.

But even the naked eye can spot some obvious - and fascinating - stuff. Because halfway down one core is embedded a single, small stone.

A small stone embedded in the mud which fell off an iceberg 20,000 years ago

It looks like it could have come from someone's driveway but it didn't. It fell off the bottom of an iceberg about 20,000 years ago.

"These big icebergs calve off the front of the glacier," Dr Bradwell says.

"Imagine the Minch was filled with ice."

The research means we know it was. This particular core is one of three pulled from the seabed off the Shiant Isles.

That's one major finding of the Britice-Chrono project: the ice sheet covering Scotland covered a much larger area than previously thought.

Dr Bradwell says: "In the past we used to think that the ice sheet only stopped when it got to the coastline - or maybe even didn't cover certain islands like the Outer Hebrides or the Orkney Islands.

"But now we know for a fact that the ice sheet extended way beyond these islands."

All the way, in fact, to the edge of the continental shelf where the seabed slopes sharply into the Atlantic depths.

So far, so tens of thousands of years ago. Why does it matter now?

Because the planet has been getting warmer. What happened here all that time ago may help forecast what is about to happen in Antarctica and Greenland.

"Ice masses on land like Greenland respond very differently to an ice sheet that terminates in the ocean like most of west Antarctica," says Dr Bradwell.

"And the British ice sheet was more like the west Antarctic ice sheet than it was like the Greenland ice sheet."

A shell handpicked from a Shetland core dated at 14,815 years old

There is an urgency to Britice-Chrono. It's been likened to cramming 50 years' worth of science into just five.

That's because massive ice shelves around west Antarctica have begun to break up but we don't know how long the process will last.

This project will give scientists valuable clues to that because it is producing much more than a snapshot in time.

Instead they are able to view how an ice sheet grew and decayed over thousands of years.

And how that decay may happen again elsewhere on Earth.