Universal basic income: The view from Finland

- Published

Driving out of Helsinki, past frozen lakes and mountains, I travelled to the far west of Finland to meet a man involved in a trial scheme to give unemployed people a basic income every month.

Four local authorities in Scotland are looking at similar plans to pilot a universal basic income, so for BBC 5 live I went to meet some people taking part in a similar pilot project which is well under way.

The idea is that everyone gets a fixed income from the state, even if they start full or part-time work.

A steering group involving local authorities in Edinburgh, Fife, Glasgow and North Ayrshire is expected to give proposals to Scottish government next month.

Grand claims are made for this concept. Some see it as a solution to broken or dysfunctional welfare systems and even as a way of solving what could be one of the biggest problems of the century - how to deal with unemployment caused by increasing automation.

It is meant to eliminate the stigma of claiming benefits, because everyone gets the same amount. It is also supposed to get rid of the so-called poverty trap, because there is no financial disincentive to getting a job - the benefit isn't reduced if people earn more.

And if what's known as the gig economy continues to grow, it might offer vital financial security for people whose incomes are variable.

That's the theory, but what about the reality?

In Finland, a two-year pilot scheme is taking place under which 2,000 unemployed people have been given 560 euros per month.

Juha Jarvinen, 39, told me that taking part in the pilot scheme had transformed his life.

Juha is married with six children and a dog, which happens to be three parts husky, one part wolf. They all live in a converted school house near the town of Kurrika.

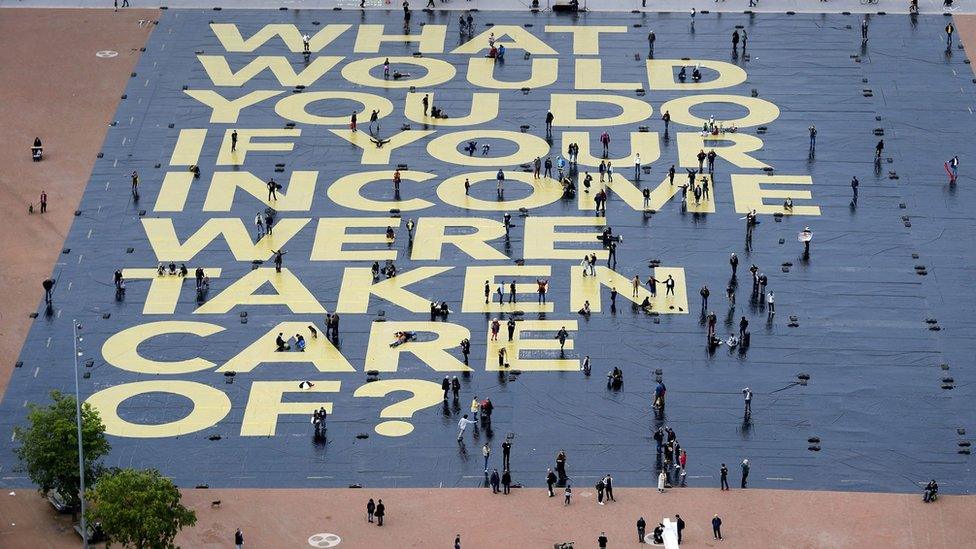

A pilot scheme in Finland is giving 2,000 unemployed people an income, instead of benefits

Over the last year, Juha's enthusiasm for the scheme and willingness to talk about it have made him a sort of unofficial spokesman.

He described his feelings when he discovered he was part of a random sample of 2,000 people selected to take part.

"I felt like a free man. I got out from jail and slavery...I felt I am back in society and I have my humanity back, so I was super happy," he said.

His situation had been desperate. Juha's small business making wooden window frames went bust after the financial crash of 2008. He said he burnt out in 2011 and then spent six years on the dole.

The pilot scheme has given Juha Jarvinen the chance to start a drum carving business.

Now he has a new business making drums. He thinks it brings in about 1000 euros a month to add to the 560 euros he receives as basic income. He said that without the financial cushion of UBI he wouldn't have been able to get back to work.

Juha has other business ideas in the pipeline, including a bed and breakfast with art classes.

Juha strongly rejected the idea that the basic income is money for nothing. He compared it to investing in infrastructure. New roads don't make people lazy because they don't have to walk. On the contrary, he said, they make people more productive.

He accepted that a few people might be content to not work, but insisted that's outweighed by the advantages of the scheme.

"Of course there is always the one or two per cent of people who would stay on their couches or do something stupid, but the wrong thing is to take a focus for those one or two per cent," he said.

Freedom and flexibility

Mika Ruusunen is from a different background. He works in IT and although he was unemployed when he was selected for the pilot, he had just found out that he'd got a new job.

For Mika, it has given him the freedom and flexibility to do a job which he really wants to do, but which doesn't pay that well.

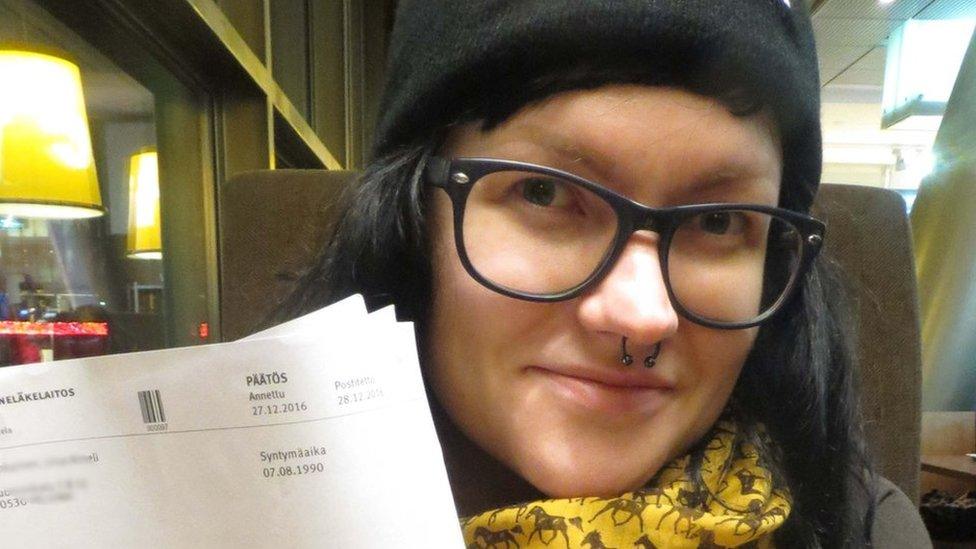

Mika Ruusunen says the scheme means he doesn't need to worry about getting a lower paid job.

Mika said he sees the world of work changing in coming years.

"The future of working will be people work for three months, six months, 18 months and then they change work.

"And the basic income will be the answer for those who have to change their work and they haven't found anything new yet."

Some analysts say that because the Finnish scheme only includes people who were unemployed, that means it isn't truly universal.

New projects may do it differently.

The Scottish government will start looking at proposals at the end of March. Other local authorities are said to be interested.

And the Finnish experience will offer useful lessons for what might, just might, be the future of welfare.

- Published16 January 2017

- Published27 December 2017