The Scottish island that buried America's dead

- Published

How the tragedy of World War One came to Islay's shores

Guidance: Contains images some may find distressing.

It is the whisky-making Scottish island, world famous for its peaty single malts and warm hospitality.

But the isle of Islay, in the Inner Hebrides, is now being recognised for an almost forgotten example of huge courage and humanity.

A hundred years ago, Islay was on the frontline in the battle at sea during World War One.

The island coped with mass casualties from two major troopship disasters just eight months apart.

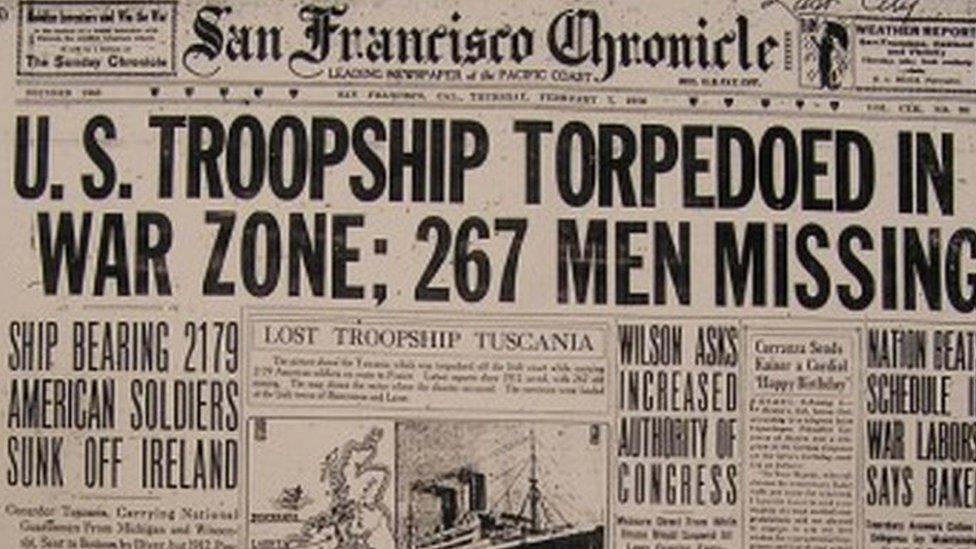

The story featured on the front page of the American newspapers

Between them, the sinkings of the SS Tuscania in February and HMS Otranto in October, claimed the lives of about 700 men in the last year of the war.

Both will be officially commemorated on Islay this week.

A century ago, the island was enduring considerable pain. It had already lost about 150 sons on the Western front, from a population of just 6,000.

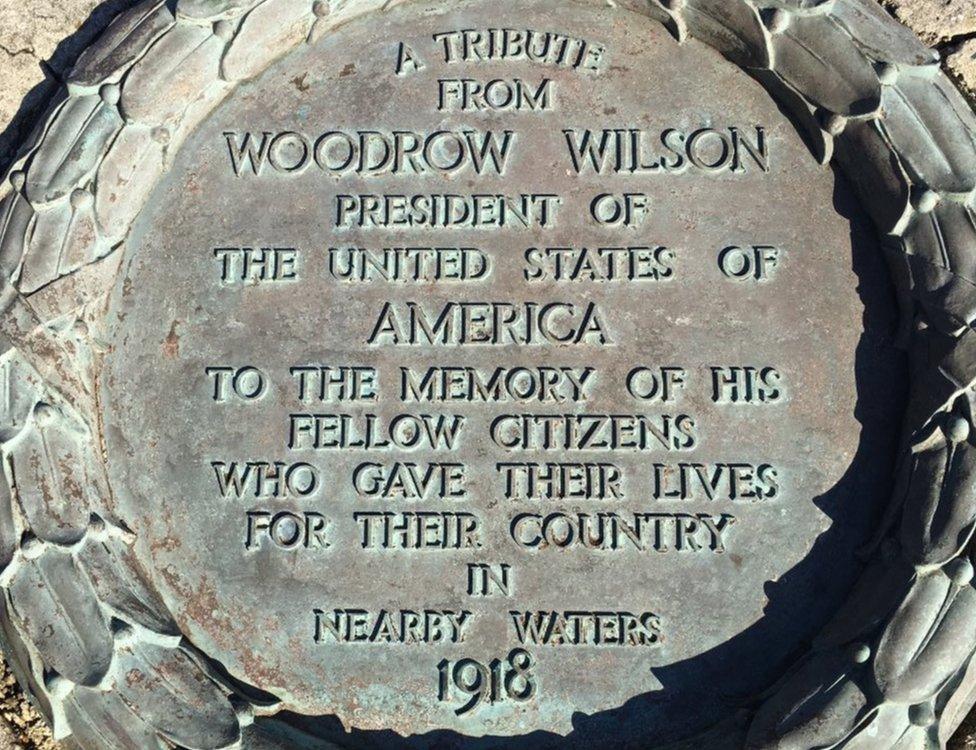

The American monument on Islay's bleak Mull of Oa

Every household grieved for someone killed in a far away field. And then the carnage of war came to them.

The Tuscania had almost completed its transatlantic voyage, carrying US troops, among a convoy of ships.

As it turned into the north channel between Scotland and Ireland on 5 February 1918, danger lurked beneath the waves.

The SS Tuscania was carrying more than 2,000 US troops when it was torpedoed off Islay

A German U-boat stalked the convoy, got the Tuscania in its sights and fired two torpedoes - one of which ripped a huge gash in its side.

It was a fatal blow. The former luxury liner, converted for the war effort, would soon be on the seabed.

The Tuscania was carrying almost 2,500 US soldiers and British crew.

Incredibly, most were rescued by the Royal Navy. But some of those who made it into lifeboats were not so lucky.

They were swept towards the cliffs and rocks of Islay's Oa peninsula and shipwrecked for a second time.

The troops were shipwrecked off the island's Oa peninsula

Private Arthur Siplon was thrown into the sea when his lifeboat capsized.

"He thought he was going to die," his youngest son Bob told me.

"But at last he grabbed hold of a rock and when the sea receded he managed to hang on and climbed to the shore."

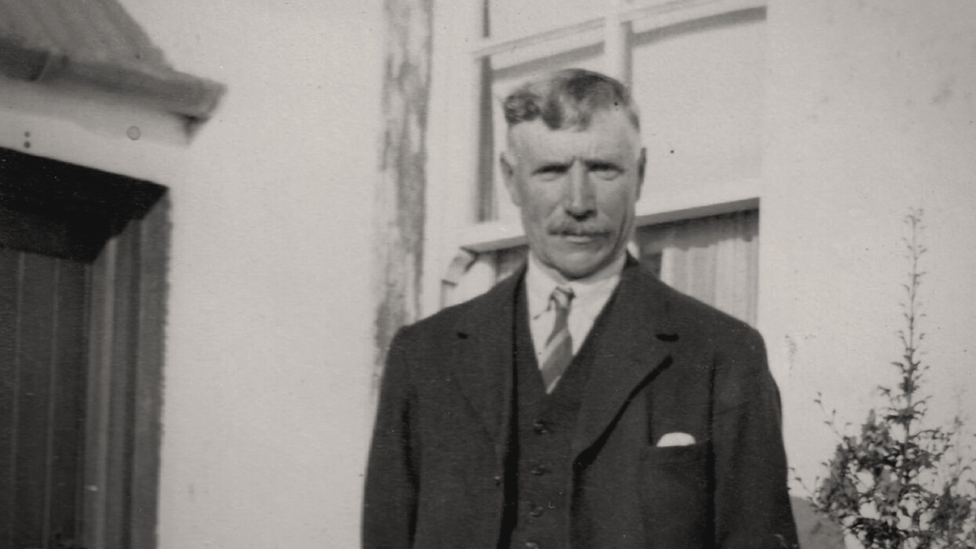

Arthur Siplon was rescued from the sea by two Islay farmers

Private Siplon was rescued by one of two Islay farmers who risked their own lives pulling men to safety.

Robert Morrison and Duncan Campbell gave food and shelter to dozens of survivors and were later awarded the OBE.

I have reason to feel particularly proud of Duncan Campbell because, while researching this story, I discovered that he was my great, great uncle.

Duncan Campbell was Glenn's great, great uncle

Bob Siplon knows that he and his family would not exist if his father had not found help on Islay.

"It's like the actions of those people 100 years ago ripples through time to affect me 100 years later.

"It tells me that what we do makes a difference" he said.

This was a massive disaster for a small island to manage. In 1918, Islay had no electricity, no air service and few motor vehicles.

The funeral on Islay of 199 American soldiers who were victims of the Otranto disaster

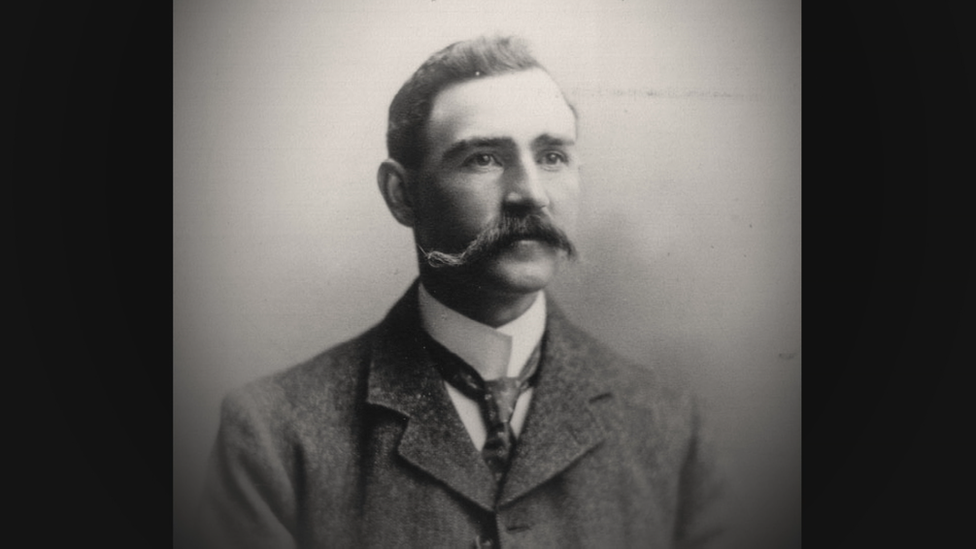

The civil authority on this almost crime-free island was a police sergeant on a bicycle, called Malcolm MacNeill.

Sgt MacNeill and his three constables had to recover, identify and bury the remains of almost 200.

Sergeant Malcolm MacNeill was the police sergeant on the almost crime-free island

His grandson - former Nato secretary general, Lord Robertson - considers their task on a scale comparable with recent terrorist attacks.

"This is like Lockerbie (air disaster) or 7/7 or even 9/11 occurring in a small community.

"A huge event taking place with deaths, bodies, survivors - the calamity that was involved".

The funeral of the American soldier victims of the Otranto disaster was attended by all the locals

Despite their trauma, the islanders worked tirelessly to bury the dead with dignity.

They did not have an American flag for the funerals, so a small group of locals hand-stitched one from the materials they had - working late into the night.

That flag has been preserved by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, which is sending it home on loan to Islay for the centenary.

The US flag made by Islay locals is in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC

The Smithsonian's Jennifer Jones is impressed by the care the islanders showed for the American soldiers washed up on their shores.

"It was very heartfelt, that people went out of their way to respect those who had recently lost their lives" she said.

Islanders pulled together to respond to the Tuscania sinking.

What they could not know is that this was only a preparation for a much bigger disaster to come.

Like the Tuscania, HMS Otranto was carrying US troops across the Atlantic in a convoy when disaster struck.

But it wasn't an act of war that sank the Otranto on 6 October 1918, within weeks of the armistice. It was a navigational error in a storm.

The HMS Otranto was carrying US troops across the Atlantic when disaster struck

As the convoy approached the west coast of Scotland in near hurricane conditions, there was confusion over their exact position.

The Otranto was rammed by another ship in the convoy - HMS Kashmir - which ripped its steel hull wide open.

The Kashmir and the rest of the convoy sailed on, under orders not to give assistance for fear of U-boat attack.

HMS Kashmir rammed into the Otranto and ripped its hull wide open

Despite the ferocious weather, the Royal Navy destroyer, HMS Mounsey came to the rescue under the command of Lieutenant Francis Craven.

"In my viewpoint, Captain Craven was a real hero. Perhaps the real hero of the event" said Chuck Freedman, whose grandfather, Sam Levy, was on the Otranto.

Lieutenant Levy was among almost 600 soldiers who successfully jumped for their lives on to the deck of the Mounsey.

Funeral of the victims of the Otranto at Kilchoman on Islay

Many others tried and failed and were crushed to death between the two ships.

By the time the Mounsey left the scene there were still hundreds of men aboard the sinking Otranto.

Their best hope was to be swept towards one of the beaches on Islay's Atlantic coast. But that wasn't to be.

Searching in the wreckage for bodies of victims of the US troopship Otranto

The Otranto was lifted by a huge wave and dumped down onto a reef that broke its back and tore the ship to pieces.

Only 21 men made it ashore alive.

Some were pulled from the sea by members of Donald-James McPhee's family.

They were shepherds and used their crooks to reach survivors - the length of their staffs, the distance between life and death.

But this was largely a recovery operation with bodies piling up along the coast.

American soldiers laid out for burial in the churchyard at Kilchoman

"It must have been so sad for them to see that" said Mr McPhee.

"Waking up in the morning to a normal day's work and hundreds of dead bodies by the evening. It must have been horrendous."

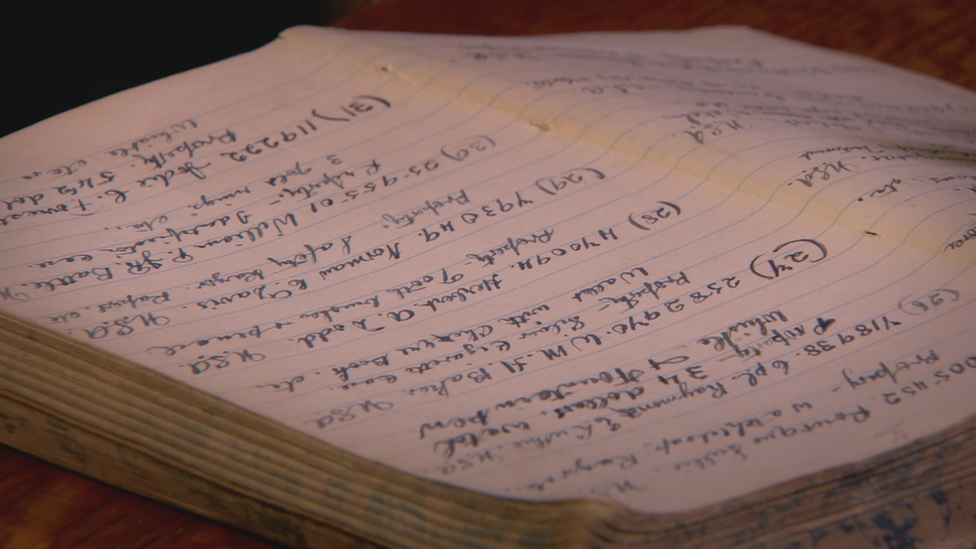

Sergeant MacNeill painstakingly recorded the details of every body washed ashore, in a notebook which now has pride of place in the Museum of Islay life.

Many of the victims were from the US state of Georgia, which is planning its own commemorations later this year.

Sergeant MacNeill painstakingly recorded the details of every body washed ashore

Some of the 700 victims of the Otranto and Tuscania disasters were never found.

The majority were buried on Islay.

After the war, the remains of the American soldiers were exhumed and returned home.

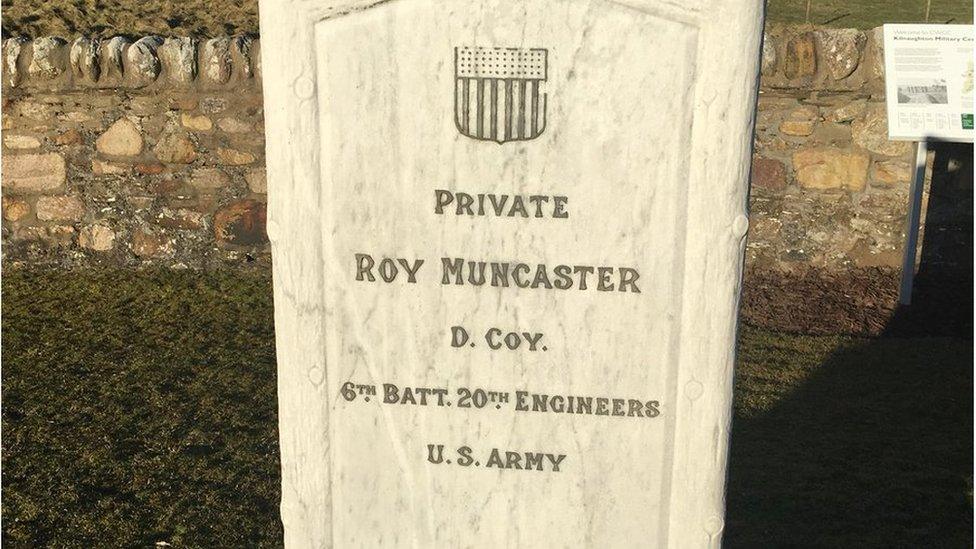

Only one US serviceman is buried on Islay

A monument was erected the year after the disaster

Only one American - private Roy Muncaster - is still on the island. At the request of his family, he was left to rest where the people of Islay buried him.

In 1918, the Tuscania disaster represented the biggest single loss of US military lives since the American civil war.

Islay's rugged coastline was a difficult place to be shipwrecked

The sinking of the Otranto accounted for some of America's heaviest losses at sea during the 1914-18 war.

Yet the stories of these ships are not well known - lost perhaps in a century of Islay mist.

There is a large lighthouse-shaped memorial on Islay's bleak Mull of Oa.

But when I was growing up on the island, the troopships were rarely talked about.

That's changing. Today, every child at my old school - Bowmore primary - is learning about them.

On Friday 4 May, Princess Anne will lead commemorations on Islay to mark the centenary of these twin tragedies.

These events will honour those who lost their lives and honour what the people of Islay did for those in peril on their shores a hundred years ago.

- Published5 February 2018