Scotland's most powerful microscope unveiled

- Published

- comments

New microscope gives hope for cancer treatment

Scotland's most powerful microscope has been unveiled.

It is expected to open up new approaches to treating cancer, Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and more.

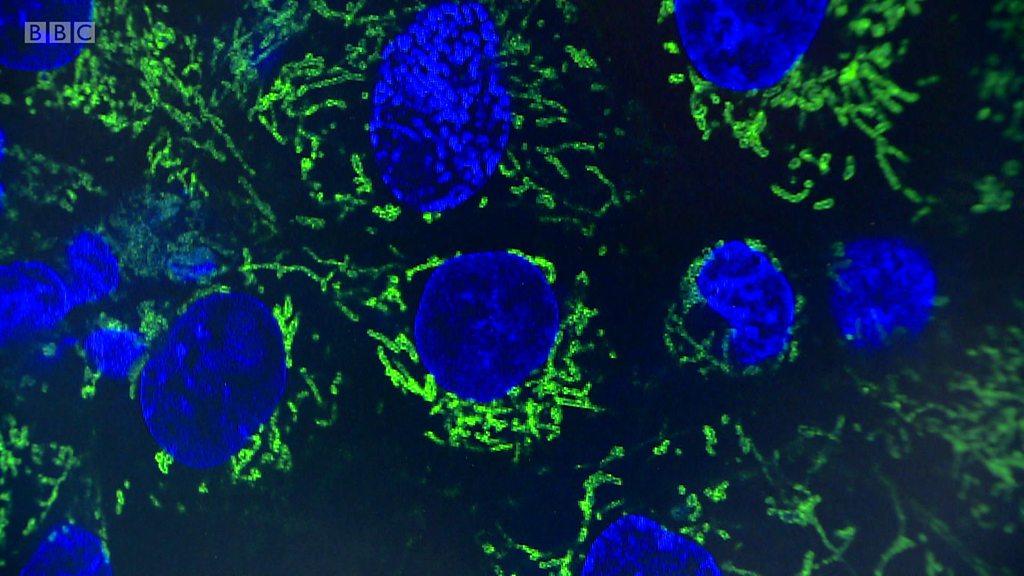

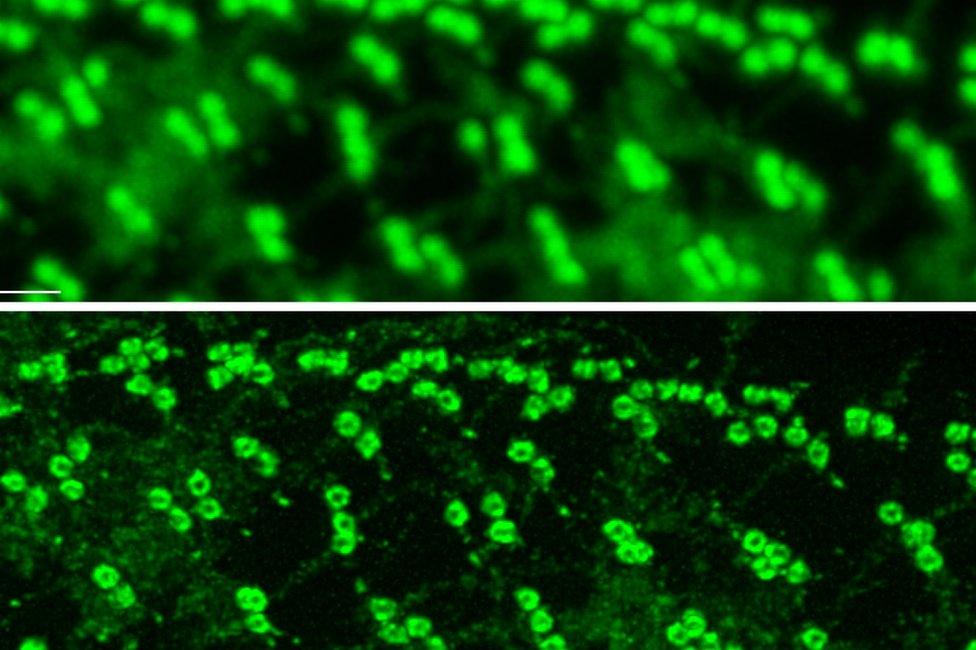

It can see things 10 times smaller than previous light-based microscopes. In fact the term "nanoscope" is more accurate as it can see objects on a nano scale - a few billionths of a metre across.

The microscope does it by breaking the limit for light.

The problem is known as the diffraction limit of light microscopy. Because light diffracts - broadly put, when it comes to a corner or an aperture it bends around it - there is a theoretical limit below which a light microscope cannot focus.

And yet here at the Edinburgh Super-Resolution Imaging Consortium (Esric) we are looking at an image previously thought impossible.

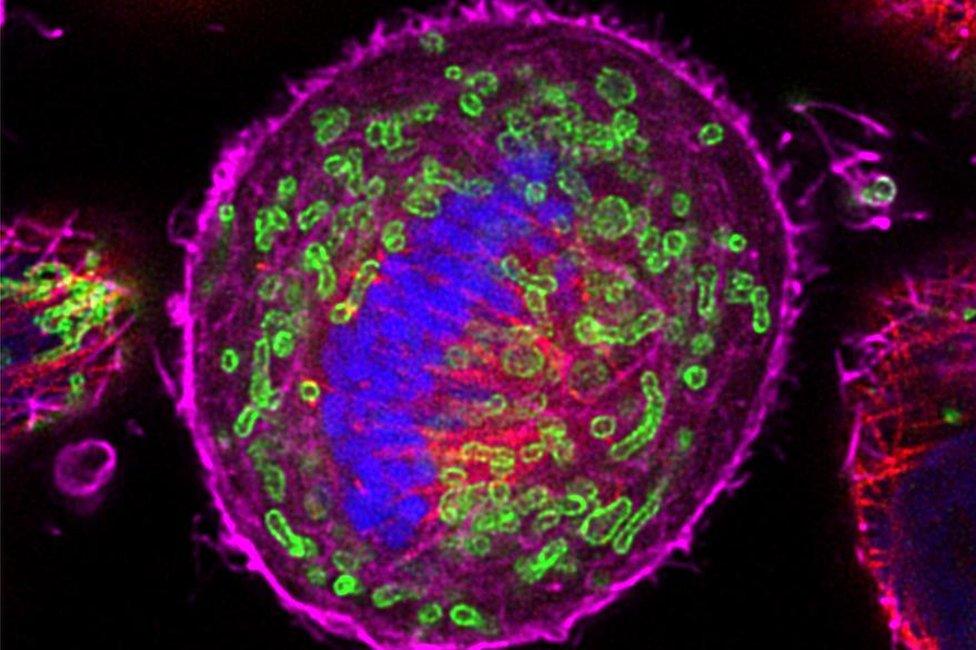

On a computer screen Esric's manager Dr Ali Dun is running an animation of a paramecium, a single-celled organism that eats bacteria.

At first its features seem indistinct. We are the diffraction limit. Then the image sharpens to reveal the cell's internal workings.

"We can see a lot more structure, things get a lot smaller," Dr Dun says.

"And so we can find out a lot more information about how structures are related to each other and where they are in space and time on a very, very small scale."

The microscope can see things 10 times smaller than previous light-based microscopes

It seems akin to magic but it is science.

Specifically, a technique called Stimulated Emission Depletion (Sted).

To deploy the broad brush again, it gets around the diffraction limit by encouraging the key part of a biological sample to give off light when hit by a laser beam while the area surrounding it is made darker.

"Biological" is the key word here. Electron microscopes can show us far smaller stuff but their samples have to be dead.

With Sted, life scientists can examine cells in action.

That is why the Prof Rory Duncan, a biologist who is co-director of Esric, is excited.

He said: "Even with a very fancy microscope - and we've got lots of very advanced systems here - we can see things which are round about the order of 250 nanometres in size. That's 250 billionths of a metre.

"These things are pretty much as small to you as Jupiter is big.

"With the new Sted system we can see things which are roughly 10 times smaller than that."

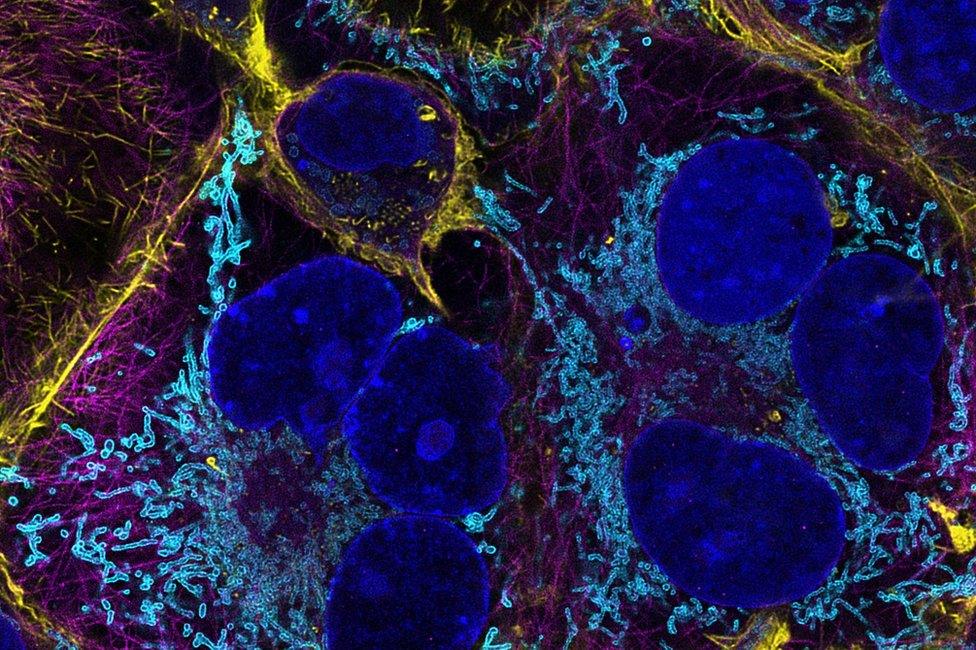

Things like watching insulin at work. That could open new avenues in diabetes research.

The nanoscope has also produced detailed 3D images of myelin, the insulation coating our nerve fibres. That offers a unique insight into how multiple sclerosis develops.

Other promising areas of research include cancer, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. Better treatments and perhaps even prevention may be possible.

But its potential goes beyond life sciences.

Materials scientists are already using it to look at new plastics. Others are studying the structures of microprocessors.

One group is even putting space dust under the system's lasers and lenses.

Esric is a joint facility of Heriot-Watt and Edinburgh universities. Much of the £1.2m cost of the new microscope has come from the Wellcome Trust biomedical research charity, with its builders Leica Microsystems also weighing in.

A criticism frequently levelled at science is that it involves knowing more about less and less. At Esric that's a virtue.

- Published8 May 2018