'My life was ruined by a blood transfusion'

- Published

Gill Fyffe had to give up her job after a blood transfusion 30 years ago

A blood transfusion after the birth of her second child in Dundee's Ninewells hospital changed the course of Gill Fyffe's life.

She was one of thousands of people infected with hepatitis C or HIV after being given contaminated blood products in what has been called the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

Over the past three decades, it has wrecked her health and taken away her ability to work.

She was forced to give up her job as a teacher at a top private school because of extreme photosensitivity which means she cannot be exposed to daylight or even light from computers.

Gill suffers from extreme light sensitivity as a result of treatment for her hepatitis

Gill told BBC Scotland: "My daughter is 30 next month so it is 30 years since I was given my contaminated transfusion.

"It has changed our lives and affected absolutely everything.

"We are now ruined. That's the facts of a contaminated transfusion, if someone takes away your ability to earn any money that's what happens."

After years of the government denying responsibility and a Scottish public inquiry failing to give sufferers satisfaction, Gill hopes a new public inquiry will finally get to the truth of a scandal that left an estimated 2,400 dead.

Sir Brian Langstaff's UK-wide inquiry will look at whether there was a cover-up by the authorities and if documents were destroyed.

Evidence gathered by Gill for a book she wrote three years ago is to be included in the inquiry.

Gill's story

When giving birth to her daughter in 1988, Gill haemorrhaged and needed a blood transfusion.

However, it was the height of the AIDS scare and there were lots of public health warnings around transmission through blood.

Gill told doctors she did not want a transfusion.

The medics held off for 24 hours but insisted it would improve her recuperation.

"In the end the hospital said I was in a life-threatening situation, so we agreed," Gill says.

Gill, who was a 29-year-old teacher at the time, says she tried to go back to work after the birth of her daughter but had to give up because she was always too tired.

"It was a funny kind of tired," she says.

"I was always cold. I used to pull my chair beside a radiator and immediately fall asleep."

"Eventually I fell asleep at the wheel. I drove off the road with my children strapped in the back of the car and wrote off the car.

"At that point we started to think there is something really funny going on here but we didn't connect it to the transfusion."

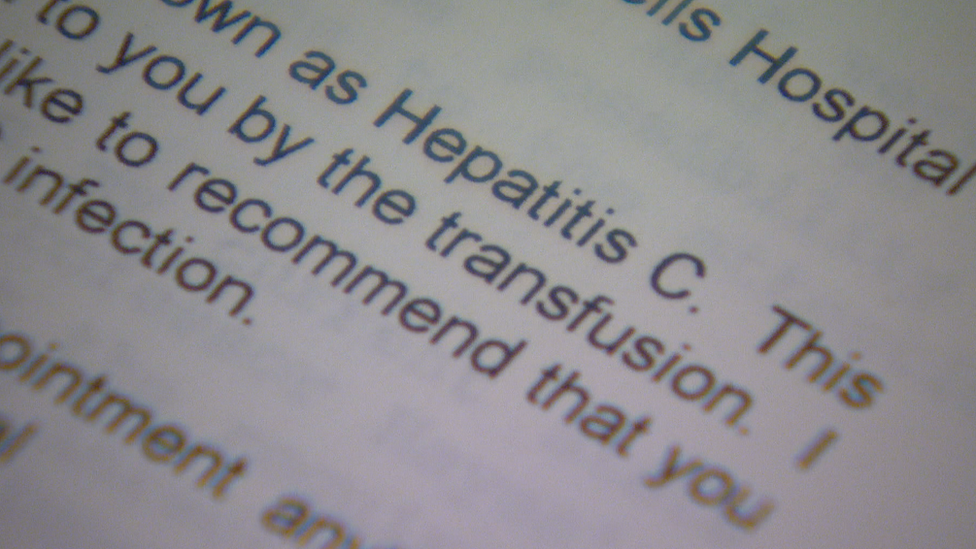

Gill received a letter seven years after her transfusion saying the blood was infected

Shortly after that, when her daughter was seven, a letter arrived out of the blue saying the transfusion was contaminated.

"As soon as I read it I knew I was infected," Gill says.

"There was a moment of calm and then realised I might have infected the children and I just went crazy."

They raced to the doctors to get everyone tested.

"Thankfully the children were not infected but they could easily have been because I had taken no precautions for seven years," she says.

Gill was contaminated with hepatitis C, a silent killer that primarily affects the liver but can also lead to many other complications.

She was treated at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary with a drug called Alpha Interferon.

"Every two days I injected myself with what felt like flu," she says.

The treatment failed.

A liver biopsy showed she had inflammation.

"I was on the way to developing liver disease," Gill says.

She says they tried to pursue legal claims but could not afford to carry on, instead concentrating on trying to improve Gill's health.

In 2000, she managed to be a "guinea pig" for a new unlicensed treatment called Ribavirin, which she took in conjunction with Interferon.

It cleared the virus to the extent she was testing negative for hep C.

Gill felt like her life had turned around.

She was offered a teaching post at Fettes College in Edinburgh and the family started to clear its debts.

However, it was not to last.

Her immune system had been boosted to kill off the hepatitis C virus and it now began to respond to light in an erratic and overactive manner.

Gill says she became extremely sensitive to sunlight

She soon discovered she could not be in a classroom where the sun was shining straight in the window.

A specialist told her to "avoid daylight" and Gill had to yet again resign from her job.

They moved to London to be near their children, who were by now at university, and continued to undergo hospital tests.

She says everybody said it was not a consequence of hepatitis but it is one of the side effects of Interferon.

"I never had any problem," she says.

"I ran about in the sun before my transfusion but since taking Interferon I can't.

"When a reaction is triggered it's horrible.

"My face swells up and blisters. The top surface sort of leaks."

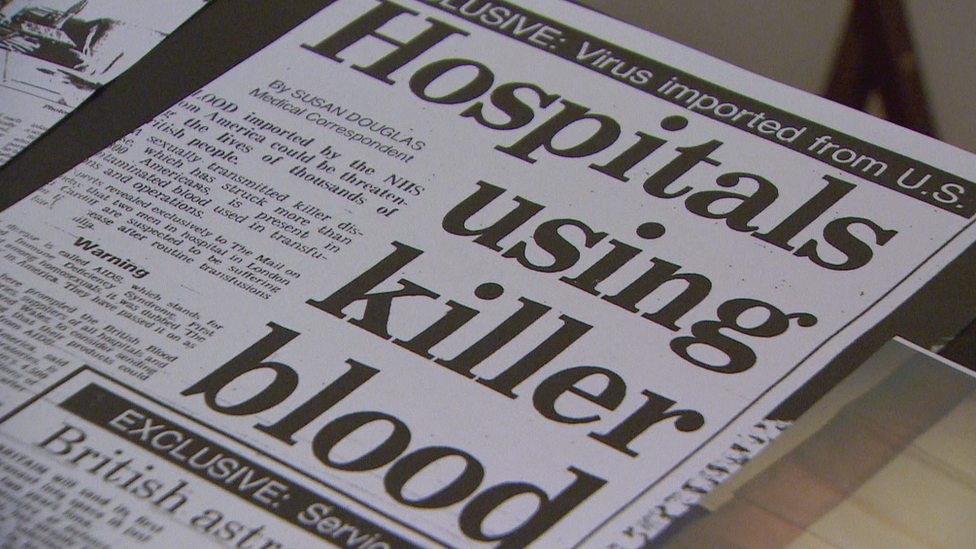

Gill decided to write a memoir of her experiences and was encouraged to tell the full story of the blood scandal.

Because she could not use a computer she trawled newspaper archives for mentions of contaminated blood and built up a dossier that is now being used in evidence at the new inquiry.

"I looked up every reference I could find and kept them all in a folder," she says.

"I put them in date-order and a 30-year story emerged."

Treatment disaster

The contaminated blood scandal of the 1970s and 1980s is often called the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

Almost 5,000 people with the blood disorder haemophilia were given a treatment contaminated with hepatitis and in many cases HIV.

Then there is a second group of people who received a blood transfusion after childbirth or an operation.

There are no solid figures available on exactly how many transfusion patients were infected before 1992.

But estimates range from about 5,000 - the same number of people with haemophilia affected - to up to 28,000, the figure suggested by a UK Department of Health analysis of the scandal.

It is thought there will still be some people living today with hepatitis C, contracted by blood transfusion, who have not yet been diagnosed.

Key issues for the Langstaff inquiry include:

whether the government could have moved faster and introduced blood screening for hepatitis C before 1991

whether officials knew about the risks of contamination but decided not to tell the public

whether enough was done to find and test patients who were given a transfusion before 1992

Penrose inquiry

The Penrose inquiry angered victims so much they burnt it

Scotland has already had an inquiry into the contaminated blood scandal.

The Penrose inquiry reported in March 2015, after a six-year wait, and concluded few matters could have been done differently.

It made only a single recommendation - that anyone in Scotland who had a blood transfusion before 1991 should be tested for Hepatitis C if they have not already done so.

There was an angry response from victims and relatives who called it a "whitewash".

Gill says: "I find it surprising that thousands of people could die unnecessarily and that was all the report had to say."

She says people were very upset by Penrose but the new inquiry is a chance to set the record straight.

She has met the team behind the inquiry and been impressed by the way they have prepared.

"After 30 years I was prepared not to be impressed but I went to London to one of their open meetings and it was astonishing, " she says.

"They were so committed, so understanding and so full of energy.

"The terms of reference were exactly what we wanted. Against our expectations we were very encouraged."

For Gill, apologies from David Cameron, when he was prime minister, and Shona Robison, when she was Scotland's health secretary, have helped change the climate around the issue.

But she says there now needs to be full recognition and compensation for the damage that was done.

- Published24 September 2018

- Published2 July 2018

- Published25 March 2015