Laser technique can identify suspicious white powders

- Published

The new technique can identify whether white powders are icing sugar or cocaine

A Scottish research team has created a new way of identifying suspicious powders without touching them.

The technique developed at Heriot-Watt University can instantly tell the difference between dangerous and harmless white powders by pointing a laser at them.

It is portable enough to be taken to where the sample is, whether a crime scene or a battlefield.

Is it a chemical weapon or paracetamol? Cocaine or icing sugar?

Our eyes present a problem because they all look the same. All we can see in each case is a white powder.

Evidence bag

That can mean strict procedures have to be imposed when a powder turns up in an unexpected place.

Crime scene tape and hazmat suits may have to be deployed and laboratory testing carried out before it is certain whether a substance is destined for the evidence bag or the rubbish bin.

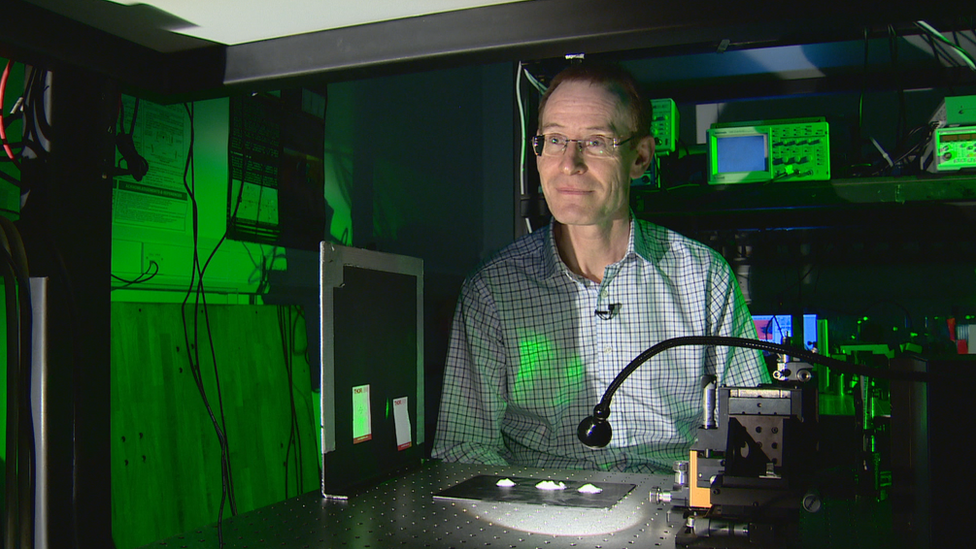

In a laboratory at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, Prof Derryck Reid has just such a problem in front of him.

On a bench sit three small piles of powder. They all look alike - but what are they?

Prof Derryck Reid uses a laser to identify white powders

The new way of finding out has been developed here: fire a laser at them.

It doesn't produce the kind of beam you can see. It uses part of the infrared spectrum at frequencies just below the visible spectrum more commonly associated with heat.

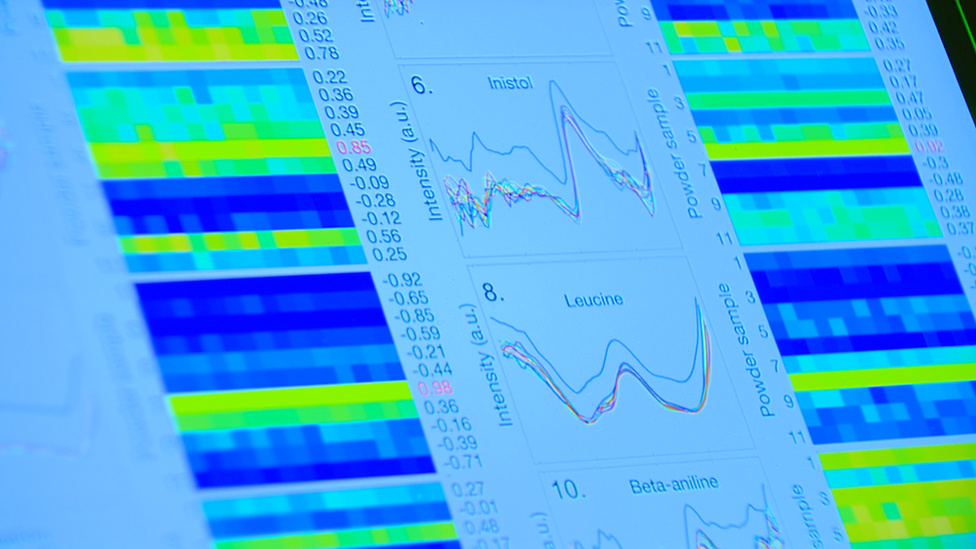

The light which is absorbed or scattered back from each powder produces a colour "fingerprint" - a pattern of wavelengths which is unique to that substance.

That is dependent on the chemical bonds in each compound.

Prof Reid says it's all to do with resonance.

"Imagine a heavy weight at the end of a spring," he said.

"It would bounce up and down with a certain characteristic period or frequency.

"The molecules in these powders are just the same but the frequencies are at the frequency of light that lives in the infrared part of the spectrum."

Each powder produces a "fingerprint" - a pattern of wavelengths uniqiue to that substance

This "fingerprint zone" in infrared light is not new to science, but using a laser is.

Until now a sample had to be brought very close to an infrared light source.

The new technique will work from as much as a metre away so a suspicious powder can lie undisturbed until it is identified.

Writing in the journal Optics Express, Prof Reid and his team say they were able to identify 11 samples.

'Range of possibilities'

They used readily available, non-toxic substances like painkillers, nutritional supplements, stimulants and a sugar.

But he says it will work just as well to identify less benign substances.

"I think there are some interesting applications, clearly in environmental science, in forensics, maybe even in pharmaceuticals, identifying kinds of drugs," he said.

"Particularly in the case of a lot of post-patent drugs the question is, have they been made in exactly the formulation they should have been made in or are they a bit different."

Dr Christopher Leburn believes there is a "whole range of possibilities" for the new technology

Not far from the laser lab, the university spinout company Chromacity is developing the technique into a product.

The apparatus is not much larger than a briefcase suitable for being used in the field.

Indeed one has already been sold for research into identifying chemical weapons.

"We think there's a whole range of possibilities that we've not thought of yet," says Chromacity's chief executive Dr Christopher Leburn.

"We're trying to get ourselves known to as many people as possible so they and us can come up with new ideas to try and exploit this really exciting technology."

Back in the lab, our three piles of mysterious white powder have been identified as harmless food supplements useful to body builders but not drug runners or terrorists.

So the crime scene tape and hazmat suits were not necessary - this time.